The Bookman, the School Teacher, and the Other Bookman

A near miss mystery, wherein Vincent Starrett does not get published, but a very familiar name in the world of Sherlock Holmes does.

This is a clue

In the 1960s, at Elizabeth Barrett Browning Junior High School in the Bronx, Dr. Evelyn B. Byrne was trying to find ways to get her all-female students to read different books. Dr. Byrne, who taught civics and English, was also adviser to the school’s newspaper, The Chatterbox. She and her young husband hit on a simple idea: Write letters to famous authors and ask them what books they read as teens, then promote those books in the school library. (For more about Dr. Byrne’s life, see the first item under “The More You Know,” below.)

Her husband (whose identity we will keep secret for the moment), was a sports statistician at the New York Daily News, working his way up to be a sports reporter. The early morning hours tended to be slow, so he agreed to type up the letters for Dr. Byrne to sign.

The question they asked was simple: “Which book or books were your favorites or influenced you most as a teenager and why?”

Incredibly, they received responses to just about every letter they wrote. Some were very brief. Architect and writer Buckminster Fuller was succinct: “The books I enjoyed in my youth were: Robin Hood, The Faerie Queen, Shakespeare, Dickens, Quo Vadis? and John Galsworthy.” Others wrote much longer essays. William Inge, for example, talked about enjoying Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, and when a little older, moving on to Of Human Bondage, “just about everything written by the late Mr. (Somerset) Maugham,” Willa Cather’s books ”because she made me see some beauty in my own environment,” and so forth for a few more paragraphs.

Promoting the letters through The Chatterbox and the school’s library was a hit!

“After displaying the authors’ letters and printing them in the school newspaper, a marked change was noticed in the girl’s reading tastes. The improvement, both quantitatively and qualitatively, was nothing short of astonishing. Books by the writers who responded to our question began to circulate more widely, as did the books and authors mentioned in those letters,” wrote Dr. Byrne and her husband.

“Suddenly, the girls read Dickens and the Brontes for pleasure, not merely as classroom assignments. Mark Twain, Robert Louis Stevenson and the Sherlock Holmes stories, normally preferred by boys, were constantly off the shelves.”

The project was a success in other ways too: The school teacher and her husband amassed more than 240 responses and one of the correspondents suggested there might be enough material here for a book.

And that’s where we find Vincent Starrett.

We only have a portion of the correspondence between Starrett and Dr. Byrne, but it’s clear she and her husband sent him a list of favorite books and Starrett’s recently reprinted work, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (TPLOSH) must have made the list.

3749 North Freemont Street

Chicago, Ill., 60613

19 February, 1966

Dear Miss Byrne:

Forgive the delay in answering your delightful letter, if you will. I’ve been laid up with flu and other miseries for a while. Your communiqué helped to restore me.

Of course Sherlock Holmes really lived! And still lives, at—let me see—say 112. He was born in 1954 (sic) you know. I’m happy to hear that he is one of your (and their) heroes, as he has been my hero since I was 10. And that was a long time ago.

It was a pleasure to write The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. It is my own favorite among my many, perhaps too many, books. Please thank the children for me, for their approval.

I was enchanted to find myself included in their list of influences—and in what lively company! It is a fine, provocative list, and I am honored to appear on it.

Again, all thanks for your letter; and my compliments to you all on the work you are doing.

Sincerely,

Vincent Starrett

(A postscript:)

Your lines about Born in a Bookshop were appreciated, too! Do we have any “juveniles” nowadays as wonderful as those old favorites of the Victorian Age? I am grateful that I had a few years of the 1890s, and still have them to remember!

VS

Before we move on, there are a few things to point out.

Starrett has revised and updated the 1933 TPLOSH for a modern audience. It was published by the University of Chicago Press in 1960, so copies would have been available in libraries in the mid-1960s. Even more recent would have been his book of memoirs, Born in a Bookshop, published by the University of Oklahoma Press in 1965. In it, he talks about the books he read as a boy, including the adventure novels of G. A. Henty. (I’m lucky enough to have one of the Henty books once owned by Starrett and will write about this and other “juveniles” in a future article.)

Eighteen months later, Starrett writes to Dr. Byrne again. It’s clear by this point Dr. Byrne and her husband were collecting permissions to use some of the 240 responses they had received for a book project. Starrett was delighted with the prospect.

My dear Dr. Byrne —

Thank you for your letter about the Chatterbox project.

By all means use my letter or any part of it you care to.

I shall be happy to be in your book.

I would be glad to own a copy of it when it is ready.

Faithfully,

Vincent Starrett

“The Chatterbox project” was published in 1971, and we might as well reveal the name of the man who helped Dr. Byrne with her correspondence and in editing the book: Otto M. Penzler. Otto, who we all know now as one of the world’s greatest collectors of mystery and detective fiction, owner of The Mysterious Bookshop and a publisher in his own right, married Dr. Byrne in 1963.

A tyro at the sports desk of the New York Daily News at the time, Otto remembered the project recently with great affection: “This was a project that took more than two years, maybe closer to three, as all the correspondence was on a typewriter—no photocopies and, of course, no computers. It was exciting to open the mail every day!”

Title page to Attacks of Taste

This book project was the first in what would become a lifetime of his published works.

“So many of the letters were little bibliographic essays,” he recalled. “We looked at them and said, ‘Wow this is really interesting.’ It was a natural idea to put them together for a book.”

The idea gathered steam after one of the correspondents mentioned the project to Andreas Brown, who had just purchased the famed Gotham Book Mart in 1967.

“Andy wrote to me and said he understood we were interested in doing this book project and we came to an agreement. The book was published in a limited edition of 500 copies, with 400 copies for sale. Each of the contributors got a copy and there were copies for Evelyn and me,” said Otto.

The book went by the unusual title of Attacks of Taste, taken from a quote by the essay Archibald MacLeish contributed: “You must remember that youngsters (as youngsters for some reason never remember) have attacks of taste like attacks of measles.”

The 70 contributors included in the book ran the gamut from Eric Ambler, Pearl S. Buck and Anthony Burgess to Thornton Wilder and Tennessee Williams. J.R.R. Tolkein was there, as was Daphne du Maurier and beat poet Allen Ginsberg. This is also probably one of the few anthologies that has Agatha Christie sharing space with John Cheever, and Anaïs Nin cheek-to-jowl (as it were) with not-yet-President Richard Nixon.

Unfortunately, Starrett did not make the cut. Otto says that with limited space, he and Dr. Byrne needed to make some tough choices from the 240 authors who had responded to their letters. But that doesn’t mean that Arthur Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes were left out. Eric Ambler, activist and writer Kay Boyle, John Cheever, Agatha Christie, Ralph Ellison, Christopher Isherwood, Henry Miller, Ogden Nash, and poet Louis Simpson all cited Doyle’s work as an influence in their youth.

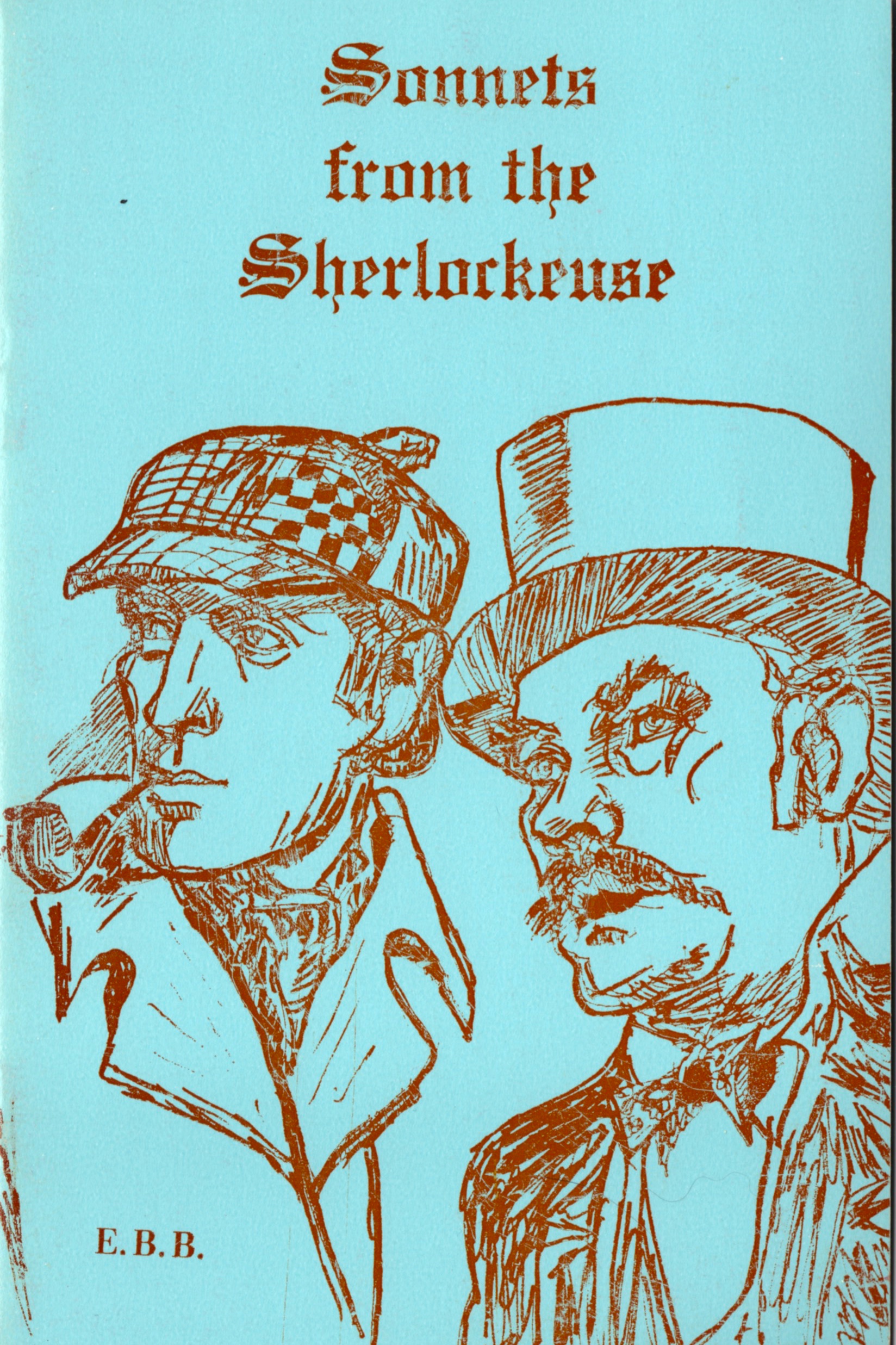

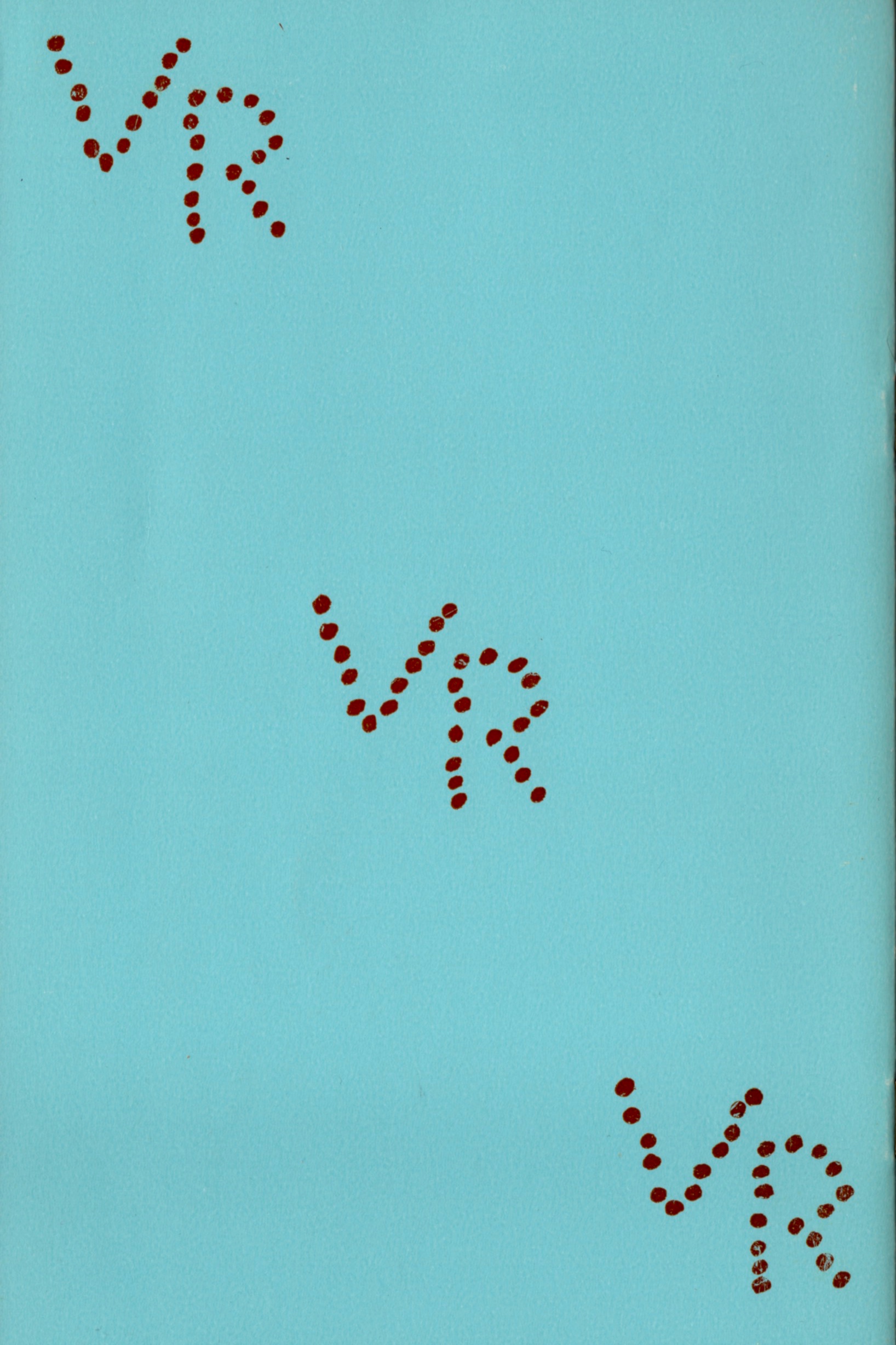

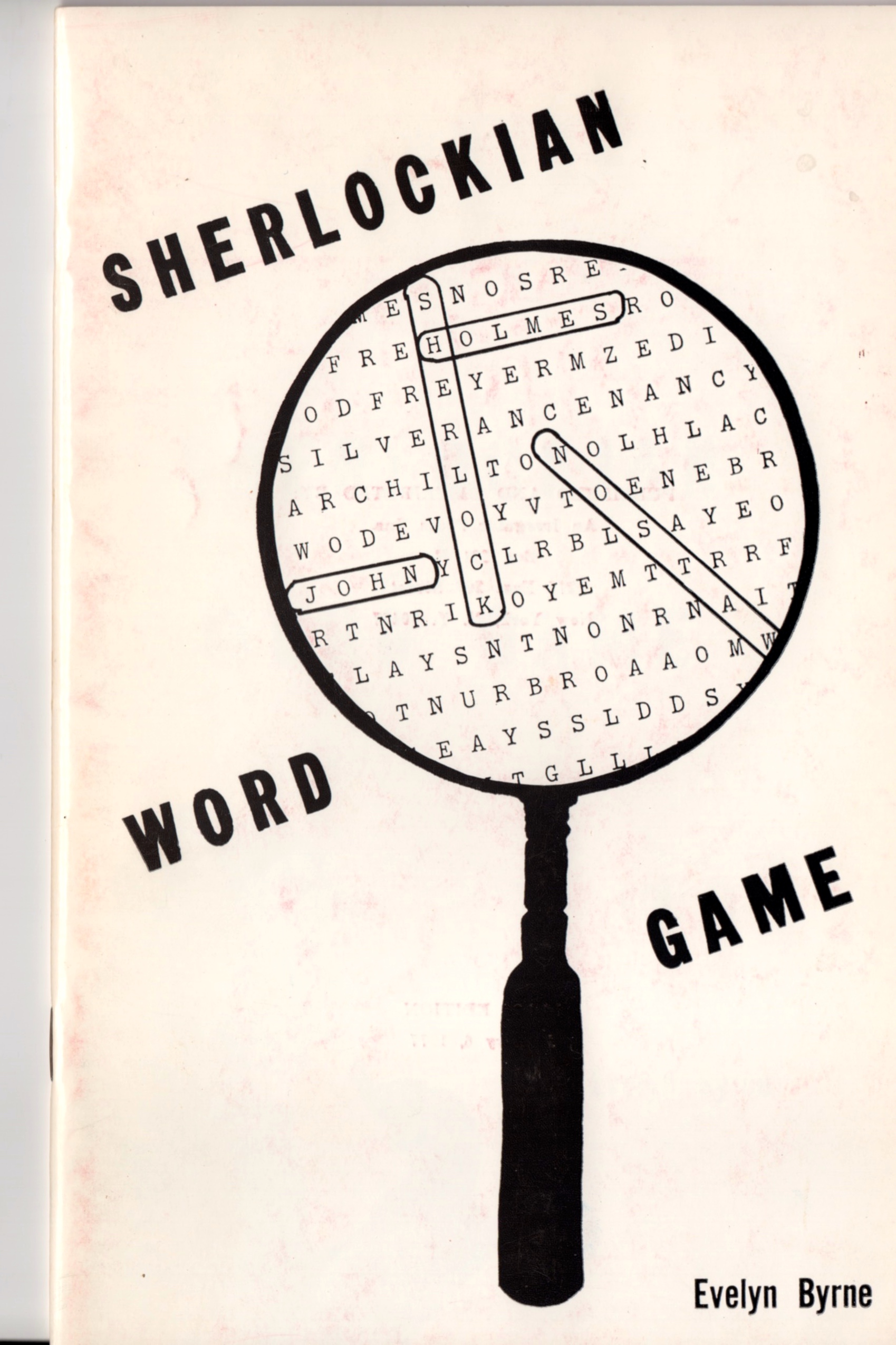

Although the Byrne/Penzler marriage ended in 1972, Dr. Byrne picked up an interest in Sherlock Holmes and over the next few years, contributed several small items, including Sonnets from the Sherlockeuse, two books of Sherlockian word games and Holmes’ Horoscope.

Before I close, I want to thank Otto for sharing his memories of this project. He generously took time during a snowy weekday in New York to reach back into his memories for details about the project.

And I owe a debt to Mattias Boström and his wizardly newspaper archival skills. He sent me the information on Dr. Byrne which helped fill out the picture of this long-time New York educator. And he did all of this in mere seconds, and shipped me links without a thought.

Thanks to you both!

The More You Know

- According to her obituary in the Poughkeepsie Journal, Evelyn B. Byrne was born on Sept. 24, 1927 in Brooklyn and received her BA from Hunter College, MA from Columbia University, MS from Hunter College and Doctorate from New York University. She taught in the New York City public schools for 37 years, and was a freelance writer for Red Book and Women’s Day. After moving to Rhinebeck, New York, she ran for mayor in 1993, was a member of the school board, president of the local AARP and was active in a number of civic and community groups. She died on Jan. 9, 2012 at the age of 84.

- The more than 600 letters by leading literary and artistic figures of the late 1960s eventually made their way into the James S. Copley Library in San Diego. The letters, in five binders, were auctioned off by Sotheby’s in 2010 for $32,500 with buyer’s premium.

- Portions of the collection were subsequently sold off in small lots, including the Starrett letters. There were the two full letters here, plus a page with a few paragraphs on it that look like the last part of a more formal essay for the book. It echoes the information in Starrett’s typewritten letter. Sadly, the first part of the essay is missing.

- Elizabeth Barrett Browning Junior High School has since closed.

- I learned how to make the umlaut mark today on my keyboard. Fün.