A Case of Identity: Vincent Starrett among the critics, Part 1

What lasting impact has Vincent Starrett left?

Like many seasoned Sherlockians, I've known the name Vincent Starrett for most of my adult life. I first read his The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes as a teen. But Starrett hoped to have the kind of fame that spread beyond the world of Holmes. In 2015, we’re going to take some deeper dives into Starrett's reputation and his lasting impact. Our first foray comes by way of Howard Haycraft, whose influential works on the history and impact of the detective story continue to resonate today.

The dust jacket to the 1941 edition of Murder for Pleasure.

Between the two great wars, mystery and detective stories were starting to gain respect among critics. Few had more influence in this effort than Howard Haycraft, a Minnesota native who was born in 1905 and died in 1991. At the time of his death, The New York Times interviewed Otto Penzler about Haycraft’s influence, particularly his seminal 1941 work, Murder for Pleasure:

" 'At the time of publication it was the most important single work of fiction-mystery scholarship ever produced,' Otto Penzler, the owner of the Mysterious Bookshop in Manhattan, said yesterday. 'It remains the most insightful, perceptive and fair-minded book ever written on the subject.' "

As its title suggests, Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story was a history of the genre, and it remains a cornerstone work for anyone interested in tracing the roots of the mystery story. It was an important book for me in the 1970s, as I was trying to understand how the Sherlock Holmes stories fit into the larger world of mystery and detection. Haycraft’s conversational style and authoritative background made it an invaluable resource.

References to Starrett are scattered throughout Murder for Pleasure, and while Haycraft lauds Starrett’s mysteries, he believes Starrett has greater strengths when it comes to the master detective of Baker Street:

"Vincent Starrett has produced from time to time some ingenious examples of plain and fancy sleuthing, though without endangering his greater eminence in the field as the devoted biographer of Sherlock Holmes; this, after all, is as one would wish it."

Starrett calls Haycraft's book, "One of the most diverting volumes of rhapsody and research in recent years. Seldom are scholarship and entertainment so happily blended as in this remarkable and necessary book."

It’s easy to see why Haycraft liked Starrett so much: The two men had a lot in common. Starrett (1886-1974) and Haycraft (1905-1991) were largely contemporaries, with Haycraft just a few years younger. Both read, admired and collected mystery novel; both were friends of Christopher Morley and members of the BSI.

Not surprisingly, they shared a love of the Holmes stories that followed them throughout their respective lifetimes.

Each was also recognized for their contributions to the literature by the Mystery Writers of America: Starrett as a Grand Master in 1958 and Haycraft with not one, but two Edgar awards.

Their collections are now housed together at the University of Minnesota’s Elmer L. Andersen Library.

I think they would have liked that.

The dust jacket to the first edition of The Art of the Mystery Story, published in 1946.

Starrett had no bigger advocate than Haycraft among the major critics of the genre, and Haycraft’s second book about the form, The Art of the Mystery Story: A Collection of Critical Essays (1946), is a prime example. The contributors names are familiar Golden Age writers and commentators: Dorothy L. Sayers, Ellery Queen, Rex Stout, Anthony Boucher, Ronald A. Knox, John Dickson Carr and many more. And, of course, Vincent Starrett was there too, represented with the namesake chapter to The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.

Pretty good company to keep, eh?

Haycraft’s admiration for Starrett was immense, as his introduction to a chapter from The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (TPLOSH) will illustrate.

I’m going to break with my usual custom of condensing such things and reprint Haycraft’s entire introduction to show just how much he honored Starrett and TPLOSH.

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes

(1933)

By Vincent Starrett

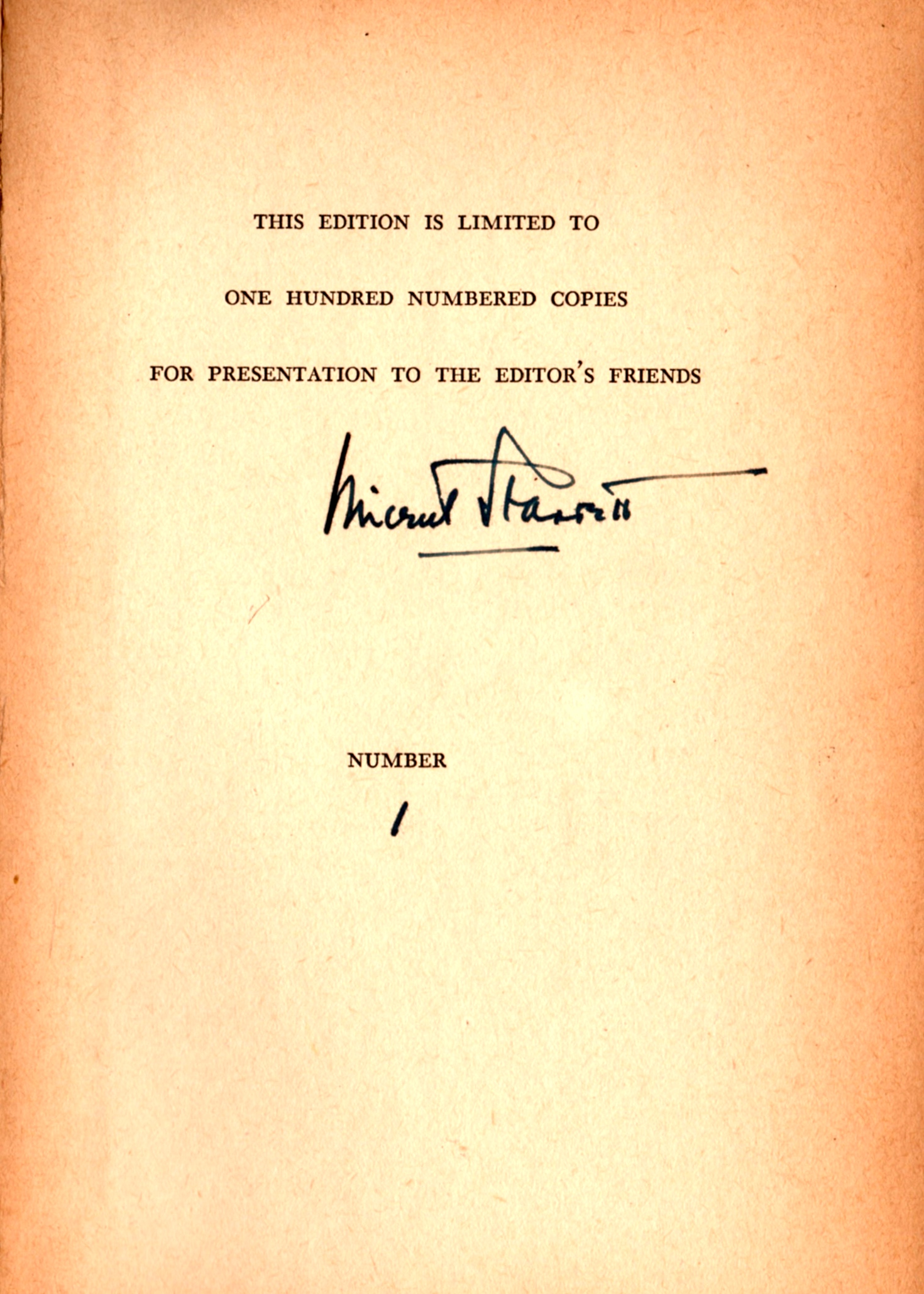

The first of the two-page introduction of Starrett's chapter.

The affection of men of good will for Sherlock Holmes has expressed itself, in recent years, in a literature sui generis: half-serious, half-humorous, often extravagant, based on the pleasant make-believe that the king of sleuths was a man of flesh and blood. As practiced by the Baker Street Irregulars of New York, shepherded by Christopher Morley, and affiliated or scion societies in such world centers as London, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Okinawa and Akron, Ohio, this pursuit of the higher verities has acquired the status of an original if minor biographical and bibliographical science that may be called, for want of a better term. Holmesiology. The studies and researches produced under this devotional aegis are classified as Holmesiana or Sherlockiana, or occasionally Watsoniana; the scriptures they interpret (known in the Baker Street vernacular as The Sacred Writings) are the narratives of John (or James) H. Watson, M.D., as transcribed for publication by a certain Conan Doyle.

Already this harmless conceit has produced a good half-dozen full-size volumes in England and America, not to mention an infinite number of shorter publications. And word arrives at press-time of the founding of a full-fledged journal, to provide the faithful with their chosen fare at quarterly intervals. (Ray's comment: See The More You Know below.)

How all this started has occasioned considerable conjecture, which need not detain us here. The truth of the matter probably is that the game belongs to no single individual, but to the unique reality of Holmes himself. With all respect to such other selfless toilers in the vineyard as Monsignor Ronald A. Knox, H.W. Bell, S.C. Roberts, Mr. Morley, and Edgar W. Smith, the finest flowering if not necessarily the earliest beginning of Holmesian scholarship occurred in the series of fond, wise, and mellow essays by Vincent Starrett which were collected between covers under the irresistible title The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, (New York: Macmillan, 1933; London: Nicholson, 1934). In your editor’s opinion, they will never be equaled, much less surpassed for sheer imaginative delight in their subject. Dealing explicitly with Holmes and Watson, they contain at the same time much that is implicit and valuable to know about the classical appeal of the detective story as a whole.

Mr. Starrett is one of the few remaining American bookmen, in the true sense of the word. Like Doyle before him, his association with Holmes seems likely to overshadow his other numerous and substantial achievements, which include a number of enjoyable detective stories of his own and some beyond-the-average thoughtful criticism of police fiction in general. The selection chosen to represent him (and Holmesiology) in the present volume is the title essay from his book.

Rarely has Starrett received such glowing praise between hard covers. I can only imagine his delight when he read Haycraft’s enthusiasm for the essays on Holmes: “In your editor’s opinion, they will never be equaled, much less surpassed for sheer imaginative delight in their subject.”

Starrett often felt his contributions to the world of literature had been overlooked. In Haycraft, he would have gotten the recognition he desired.

It should be noted that Haycraft did not just admire Starrett’s work on Holmes. Starrett was the editor of The World's Great Spy Stories and as such contributed a detailed introductory essay. When Haycraft gets to the issue of spy stories for The Art of the Mystery Story, he defers to Starrett’s knowledge.

"I seem to have discussed exclusively the spy novel, with almost no reference to espionage in the mystery short story. The omission is of no consequence. All that needs to be said about the spy short has been said superlatively well by Vincent Starrett in his anthology World’s Great Spy Stories (Forum, 1944)."

Elsewhere in the same book, Haycraft calls Starrett’s spy book “urbanely annotated.” Later, when Haycraft has to recommend an edition of Charles Dickens’ The Mystery of Edwin Drood for inclusion in his list of cornerstone novels, he picks the edition edited by Starrett, saying “Starrett’s is the first scholarly edition of the text of Dickens’ unfinished novel; its introduction is a fine summary of the various theories about its proper conclusion.”

And, in a final nod that must have made Starrett quite proud, Haycraft includes his 1936 mystery novel Midnight and Percy Jones in a list of the genre’s best.

Starrett recognized Haycraft’s generosity and repaid it with praise in his “Books Alive” column.

For example, when The Art of the Mystery Story was reprinted in 1961, Starrett acknowledged enjoying it all over again. Starrett noted that Holmes’ popularity continues to grow and that he is “a more commanding entity in the world than most of the warriors and statesmen in whose present existence we are invited to believe.” He goes on to praise the quality of the contributors to the volume (he modestly leaves out his own name) and says Haycraft's book is “urgently recommended” to anyone who loves mysteries.

So, for those who use Haycraft's books to research the history of the mystery story, Starrett's reputation as a major figure—particularly when it comes to Sherlock Holmes—seems well established.

That's all for now. We will come back to the subject of Starrett and his reputation among the critics later this year.

The More You Know

- Haycraft’s book was going to press just as the first issue of The Baker Street Journal was slowly working its way to publication.

- Buried somewhere in the boxes that hold too many books for too few shelves is a copy of Haycraft's 1936 book, The Boys' Sherlock Holmes. Despite the sexist title (which would not have raised eyebrows in the 1930s), Haycraft's loving introduction shows he and Starrett shared a sentimental affection for the Baker Street sleuth. The book was revised and reprinted (still with the sexist title) in 1961.

- The Baker Street Irregulars invested Haycraft in 1950 as "The Devil's Foot."