Watching two Sherlockians at play

We’re going to talk a little today about the corresponding friendship between Vincent Starrett and Cornelis Helling, (Sept. 9,1901-March 10,1995. Chances are you’ve not heard about Helling before. He was a shy Sherlockian and was not a frequent contributor to Sherlockian publications. But he was a loyal correspondent and Starrett greatly valued their long and warm friendship.

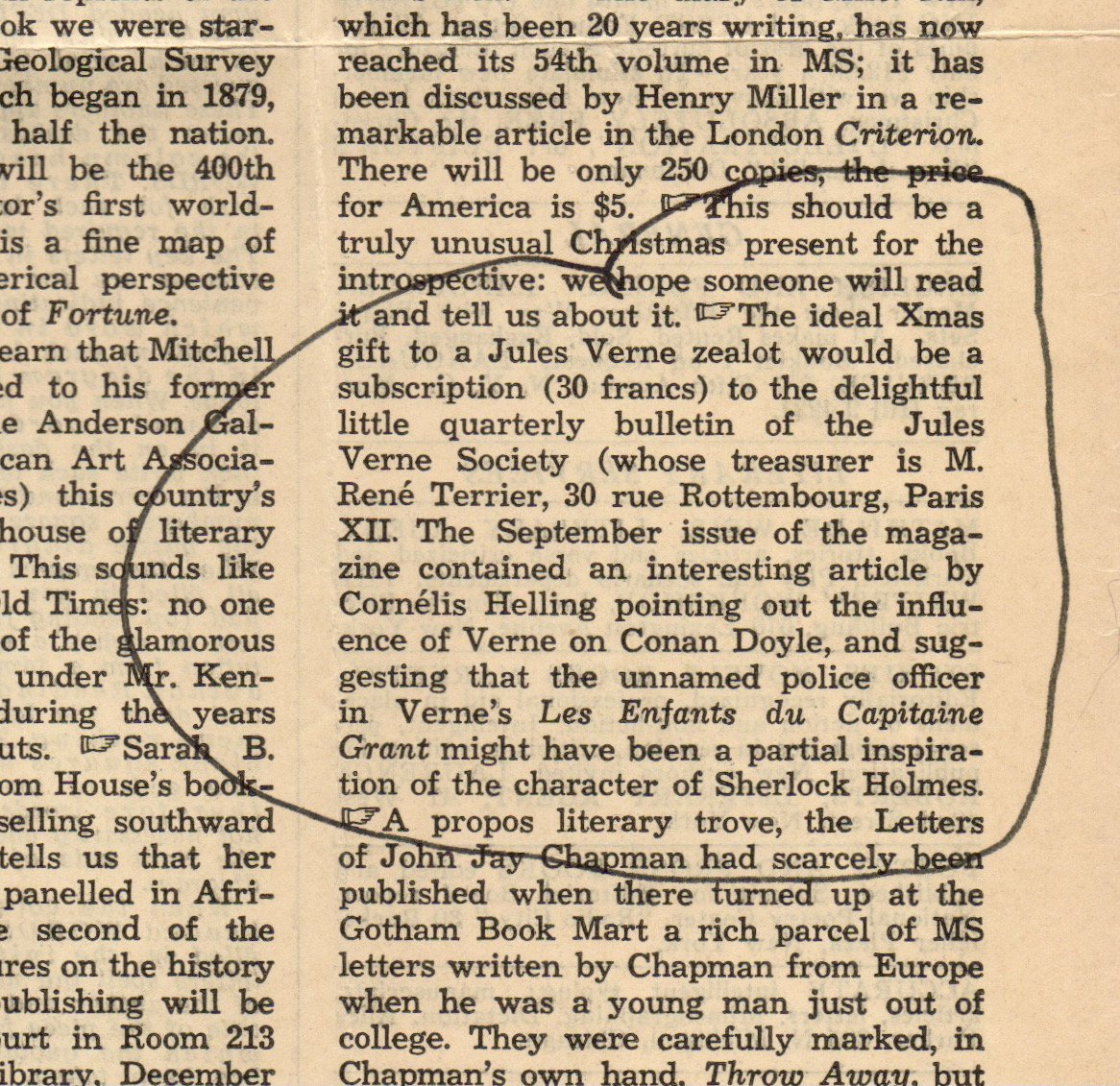

(Starrett shared some information about Helling’s activities with Christopher Morley, who mentioned them in his Trade Winds column. Click on the images below for more information.)

Helling was a minor government official and a rather shy fellow, but his imagination was sparked by the Sherlock Holmes stories of Arthur Conan Doyle and the inventive works of Jules Verne. In 1935 he became an original member of the Jules Verne Society of France and served as its vice president for 30 years.

While Starrett traveled (when funds permitted), Helling spent his entire life in Amsterdam, although he may have made some trips to other parts of Europe.

A review of 1939 “The Hound of the Baskervilles” starring Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce from Algemeen Handelsblad, a leading daily Dutch newspaper.

In return for news about Sherlock Holmes in the United States, Helling supplied Starrett with information about Holmes in Dutch newspapers, like this review of the 1939 “The Hounds of the Bakervilles” starring a baby-faced Basil Rathbone and NIgel Bruce.

The clipping is from a large scrapbook kept by Starrett, with stories primarily from the 1930s and 40s. Several of the stories are in Dutch, like this one.

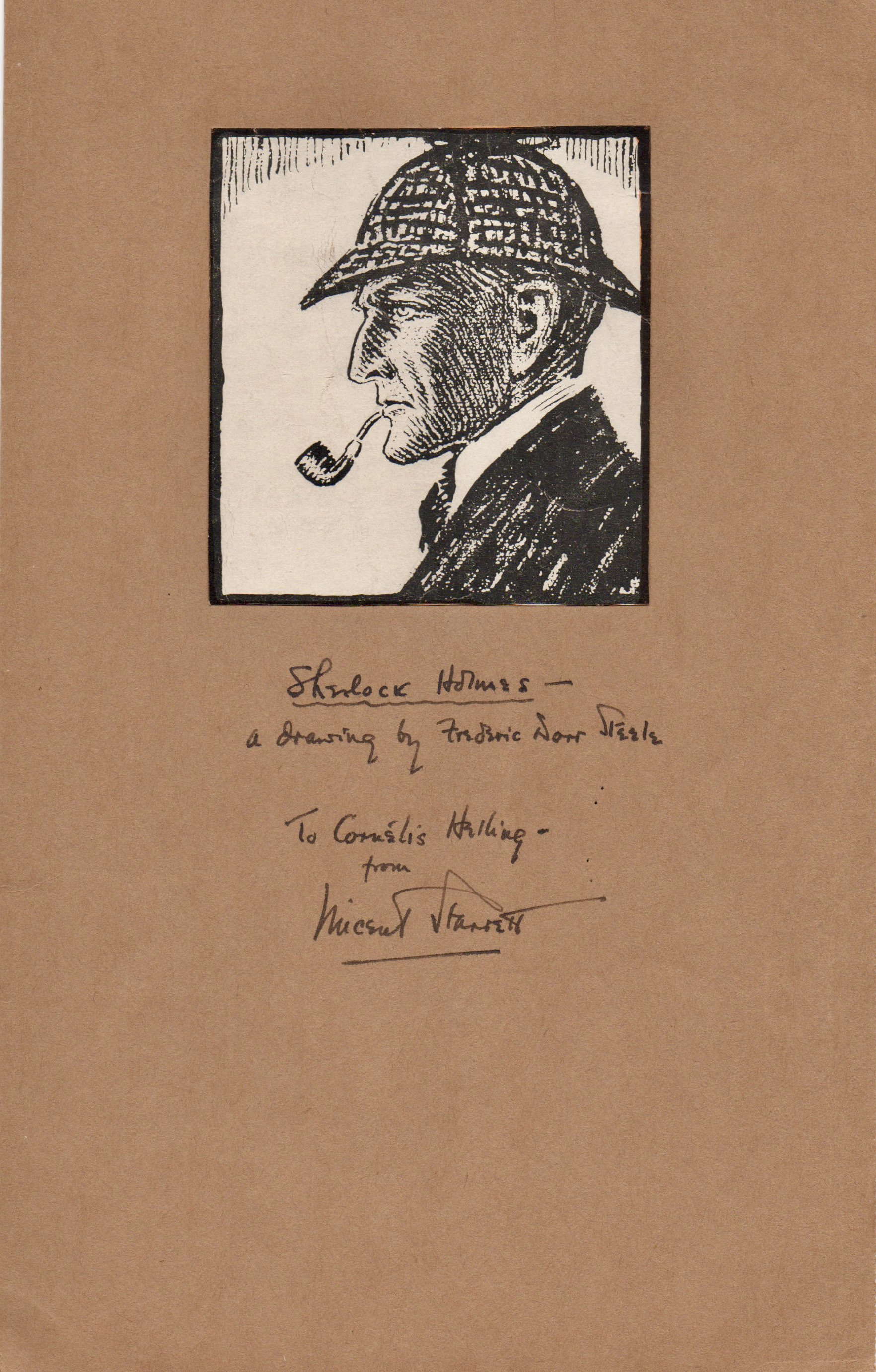

(Starrett also sent Helling mounted images showing Frederic Dorr Steele illustrations of Holmes. Click on the images below for more information.)

Helling started writing to Starrett in Chicago during the 1930s after learning about the latter’s expertise in Sherlock Holmes. (It is possible that the 1933 publication of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, helped spark the correspondence.) It was the start of a lifelong letter exchange that both men enormously enjoyed.

Helling saved every one of Starrett’s letters. I have about 40 of them from the 30s to the 50s, and they read like the joyful exchanges of two boys who have become penpals and find they share a fascination for the same fandom. Which is about right when you think about it.

All went well between the two men until World War II interrupted their correspondence during which time the Germans occupied the Netherlands for more than four years. For a period of time, Starrett did not know if Helling was dead or alive.

The letter reproduced here shows the first time they were able to renew their corresponding acquaintance after the conflict ended. Let us see what we can deduce from Starrett’s letter.

We can infer that Starrett received two postcards from Helling. The whereabouts of those postcards are not known. They must have reported good news, because Starrett begins his response with a warm and enthusiastic welcome, as if the two men had just unexpectedly met on a city street after a long separation. Starrett then gets right down to the basis of their friendship.

“Now we can begin again to pay attention to the really important matters of life, such as our research into the Life and Times of Sherlock Holmes.”

And there you have it. For Starrett, who always preferred books and fictional characters to the troubling world of reality, it’s as if the second World War has been swept away and is nothing more than a bad memory. Now, it’s time for Starrett and Helling to play.

And what more playful group to discuss with Helling than the Baker Street Irregulars? Owing to financial difficulties and a need to stay in Chicago with his emotionally fragile wife, Starrett only attended one dinner, the December 1934 meeting of the New York Irregulars. He would get invitations for each succeeding dinner until his death, but he never went back.

Helling’s membership card in Starrett’s chapter of The Baker Street Irregulars.

What Starrett did have was a broad social group of Sherlockian friends in Chicago. He, like others around the country, had started his own chapter of the Irregulars in the early 1940s.

In this letter, Starrett announced he planned to include Helling—in absentia—at the next meeting of the Chicago Irregulars, also known as the Hounds of the Baskerville (sic).

“I shall read your card to my group, the Baskervilles, and tell them about you; for you are, of course, an honorary member of my particular group.”

Starrett’s gift of membership to Helling was not uncommon for this time period. He casually offered membership in the Chicago Irregulars frequently, especially to those with whom he felt a special bond.

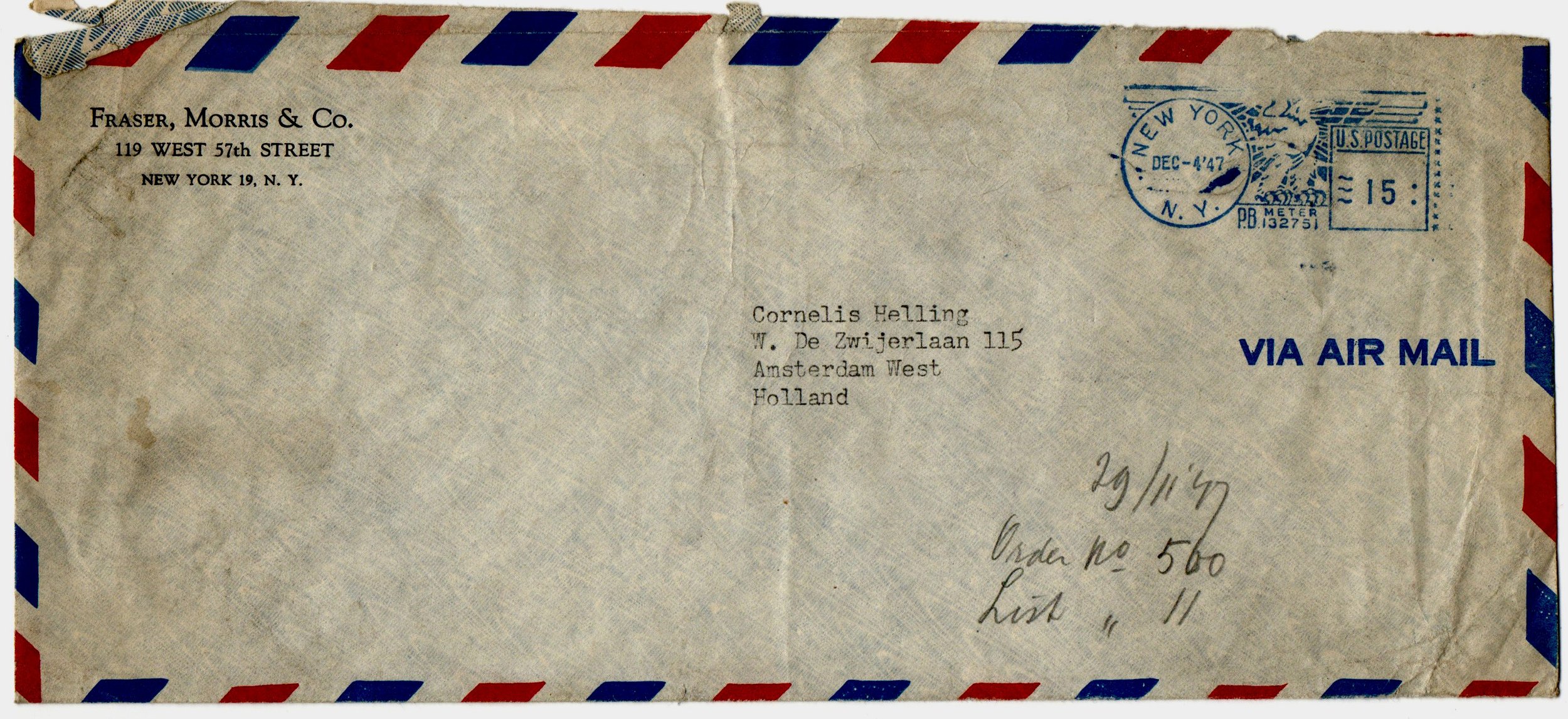

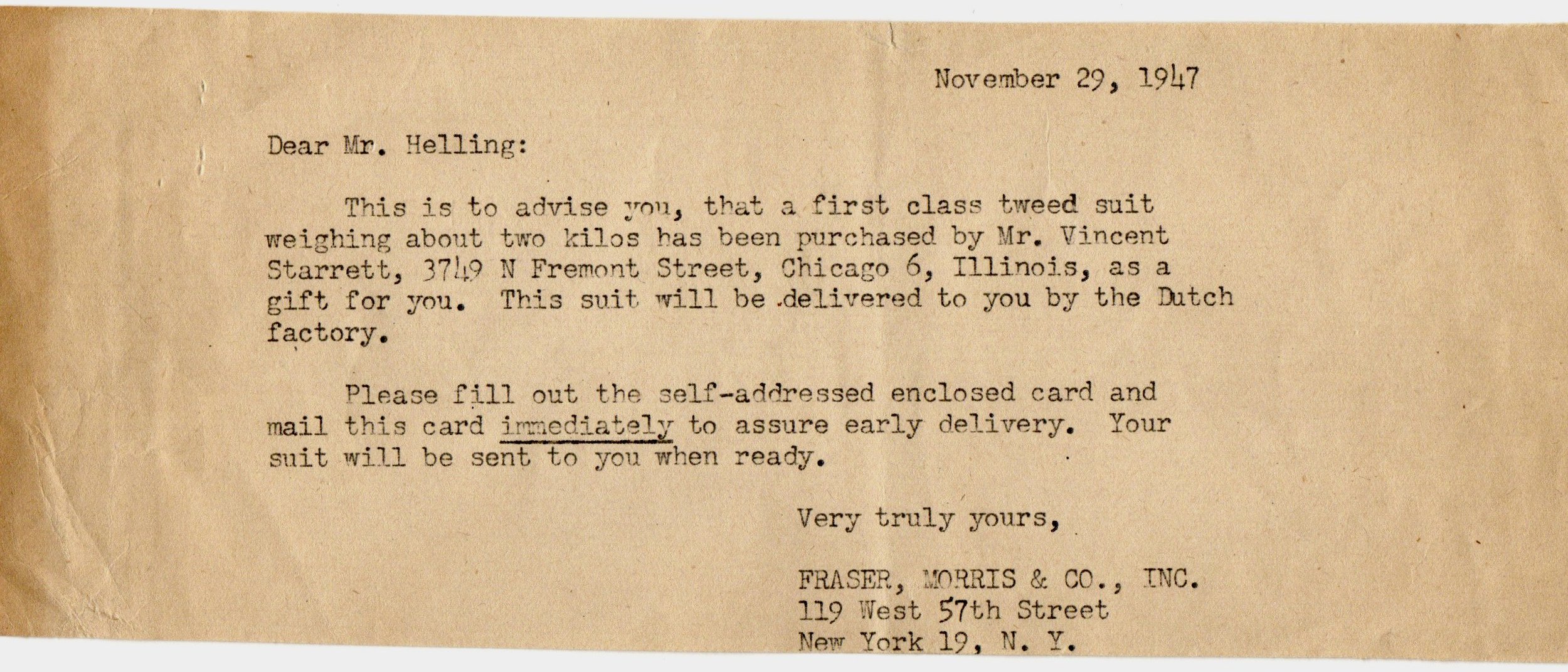

(Below: Getting a good suit was not easy in Europe after the war due to rationing. Here Starrett has purchased a suit as a gift for Helling. It’s likely Helling paid Starrett back in books, his favorite currency.)

Returning to the letter: It’s clear Starrett can’t sign off without encouraging Helling to once again begin hunting through Amsterdam bookshops for new or “curious” editions of Doyle and Verne. It might seem that Starrett was being abrupt in not asking Helling more about the war and its impact.

The truth is Starrett just cared about books a great deal (often preferring them to people) and didn’t want any opportunity to get past him. After all, it was Starrett who said,

“When we are collecting books, we are collecting happiness; and if that be not the absolute quested by us all, I do not know what is.”

To this point, Starrett’s letter would be enough to warm any book-lover's bindings, but Starrett adds a postscript, noting that he has slipped an invitation to the Baker Street Irregulars in with his letter, “for your amusement.”

This is now a rather rare document, made all the more notable for its announcement that the first issue of The Baker Street Journal was being published by Ben Abramson. Starrett says he will try to get a copy for Helling’s files. Subsequent letters make it clear that Helling was not a highly paid government official and was not able to afford an international subscription. Starrett, who periodically suffered penury himself, seems to have subsidized Helling’s subscription for at least a few years.

The enclosed Baker Street Irregulars invitation is from Edgar W. Smith, who, as Buttons for the Irregulars, had assumed the administrative duties from founder Christopher Morley. Like Starrett's letter, the invitation is also a snapshot of the BSI at an important moment. Some things had not changed during the war years. For example, the Irregulars were returning to Parlors F&G of the Murray Hill Hotel, its home since the revival of annual dinners in 1940.

Not everything was the same. Smith was at some pains to point out that the dinner’s cost had risen to a breathtaking $11! And, mindful of Morley’s desire to keep the Irregulars small, he made a hard case for limiting the dinner to 48 people, forcefully arguing against unexpected guests:

“The rule against the bringing of guests (will) be observed with the greatest severity.”

But the major news in this letter is the first public announcement of The Baker Street Journal, the Irregular quarterly which was to undergo its own great hiatus after four years, before coming back for a long and healthy run which continues today.

Think of it: Diners each got a copy of Volume 1, Number 1 of the Journal and could have many of its contributors sign their articles right there. It would have been a remarkable night for this moment alone.

Starrett’s gesture in sending the invitation reaffirmed their corresponding friendship. War never again held up their fun with “the really important matters of life.”

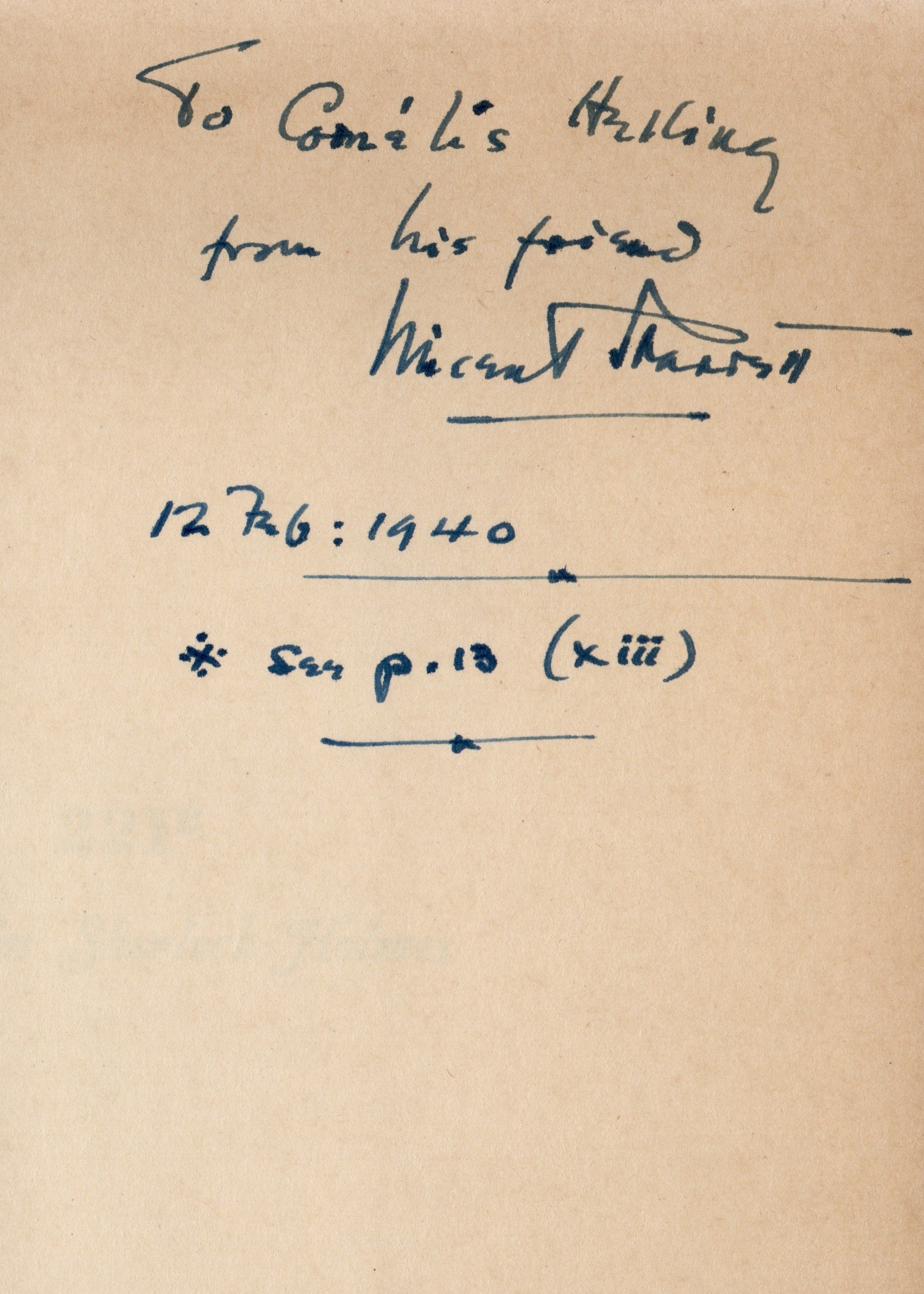

(Starrett included a mention of Helling’s Sherlockian activities in his introduction to 221B: Studies in Sherlock Holmes, published in 1940. He then inscribed a copy for Helling. Click on the images below for more information.)

The two men continued to write to each other, sharing personal and Sherlockian news, until Starrett’s death in 1974 at the age of 87.

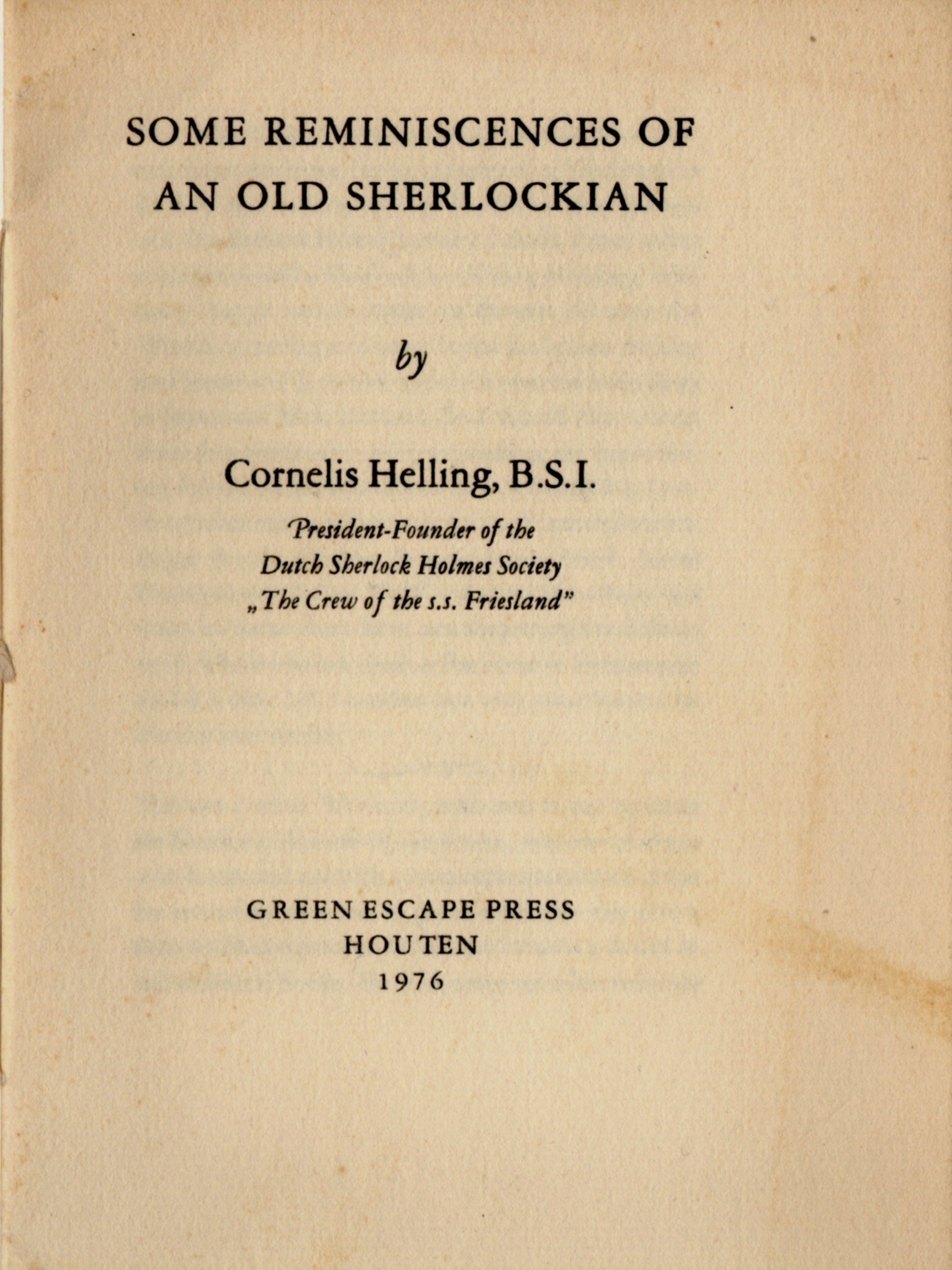

Helling had this little pamphlet published in 1976 with a few anecdotes about his life as a Sherlockian.

They had a lot to talk about. In addition to his interest in Verne, Helling was a founding member of the Dutch Sherlock Holmes Society in 1952. He didn’t attend a BSI dinner and never visited the United States. Nonetheless, Helling was invested in the Baker Street Irregulars in 1961 as “The Reigning Family of Holland.” He died in 1995, at the age of 94.

Their correspondence is a testament to the friendships which arise from a shared affection for investigating “the Life and Times of Sherlock Holmes.” Those friendships, then as now, are the basis for the ongoing enjoyment many of us share in this fascinating hobby.