Vincent Starrett, Disciple or Thief?

Was Starrett guilty of piracy? Arthur Machen thought so.

When the Welsh mystic accused Starrett of piracy, all hell broke loose.

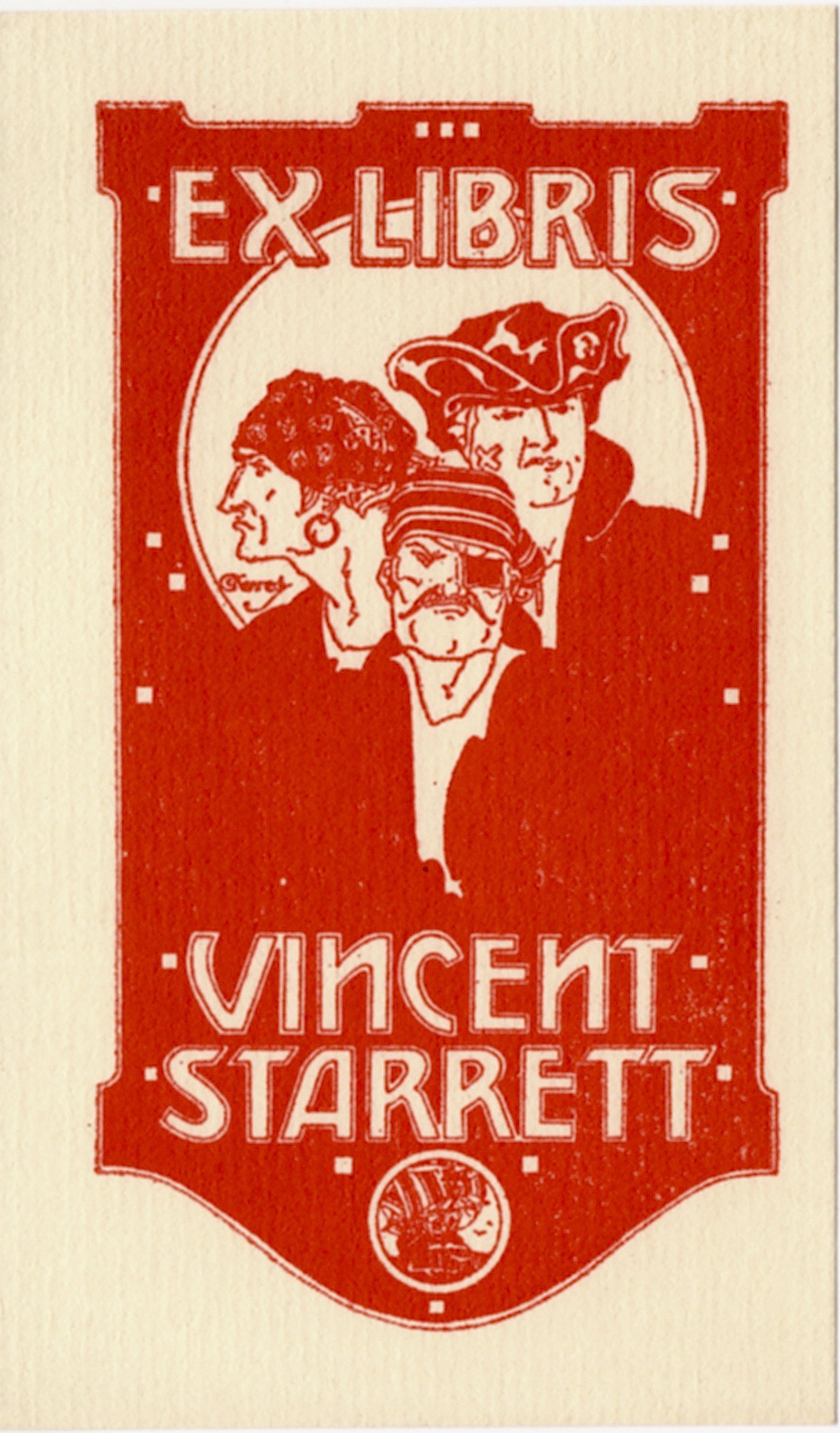

The title page to Starrett’s 1918 booklet.

The friendship between Vincent Starrett and Arthur Machen started out well. Machen (born in March of 1865) was nearly 20 years Starrett’s senior. He had produced a number of articles, reviews, short stories and a few novels by the time Vincent Starrett discovered him in the early 1900s. Starrett, a young newspaper reporter in Chicago, was entranced.

He wrote elegiac essays about Machen for Reedy’s Mirror, then had them reprinted as one of his first booklets, Arthur Machen: A Novelist of Ecstasy and Sin. Here in one humble volume of 35 pages was everything Starrett wanted the world to know about his hero: his mystical view of universe, his lyrical use of language and the manner in which he pierced the deeper mysteries of life and love. Starrett was enthralled and clearly idolized the Welsh writer. Starrett’s booklet had a small print run of 250, but became influential over time.

He promoted Machen shamelessly among his fellow Chicago writers who joined in Starrett’s chorus of tribute. They wrote newspaper articles which prompted magazine articles and soon a Machen boom was taking off in the United States. Starrett was gratified and proud.

Machen showed his appreciation by dedicating his 1922 book The Secret Glory to Starrett, who then redoubled his efforts.

The dedication and first page to The Secret Glory, published in London by Martin Secker circa 1922.

Having churned the waters by the early 1920s in Machen’s favor, Starrett decided the time was right for new Machen books in the United States. He made arrangements to publish them through Chicago booksellers and publishers Pascal Covici and Billy McGee. Starrett oversaw publication of The Shining Pyramid in 1923 and The Glorious Mystery in the following year, both books of essays and other work that had not been published previously in the United States.

Oddly, while he had Machen’s permission to pursue publications, Starrett didn’t share the details of what materials were being published or exactly when the books would come out. He also failed to ensure that Machen would earn money from these ventures.

Click on the illustrations below for more.

Just as newspapers started reviewing the second book, an open letter from the New York publishing firm of Alfred A. Knopf (who put out books with the Borzoi imprint) was sent to booksellers.

I feel it is my duty to call to the attention of every bookseller the following facts in regard to certain practices which do not yet seem to be quite dead in the United States. Arthur Machen’s works have come to be exclusively associated with The Borzoi—with the authorization, it is needless to remark, of Mr. Machen himself. However, last year there appeared a collection of essays by him entitled The Shining Pyramid, edited by Vincent Starrett and published by Covici-McGee. These essays had appeared some time before in various English periodicals and were therefore uncopyrighted in the United States. Mr. Machen was not consulted in any way about this book which was a deliberate piracy of his property.

Now this same publisher and the same editor have brought out The Glorious Mystery, also in a pirated edition. Mr. Machen has just written us as follows:

Dear Mr. Knopf:

I find to my very great annoyance that Starrett is again pirating my property. I need scarcely say that I know nothing about The Glorious Mystery, Covici-McGee are announcing.

In any case, please understand that you have my full authority to repudiate The Glorious Mystery and to state that it has been done without my authority, consent or knowledge; in any manner and through any medium which may strike you as practical.

Yours Sincerely,

(Signed) Arthur MachenI believe that these facts are worthy of your serious consideration.

Yours faithfully

(Signed) Alfred A. Knopf

President

June 14, 1924 brief from The Chicago Tribune.

It was a surprising blow, made worse when newspapers started to take note. The Chicago Tribune, the most powerful newspaper in Starrett’s home town, agreed that the claims were worth discussing. In a June 14 article with the headline “Arthur Macheniacs,” the anonymous writer takes the side of the hometown boy over the Welsh writer.

The key paragraph argues: “The point is probably that a man who for years has written without the slightest public success and who has had but two or three passionate adherers—of which Mr. Starrett has long been the most vociferous—suddenly finds himself by way of being a best seller in his metier and he is confused about the whole thing.”

Confused is certainly a word that applies. The confusion is rooted in the series of letters between Starrett and Machen that started in 1915. Sorting all this out will require a bit of backstory.

Sorting out how all this happened is like hearing one side of a phone conversation. With one exception, we only have Machen’s letters to Starrett, so the record is incomplete. We also have these letters because after Starrett’s death, his friend and literary executor Michael Murphy published them in a book called Starrett vs. Machen in an attempt to finally settle the score. So Murphy certainly had a point of view in publishing what he did.

The book shows the two wrote on friendly terms for years, with Starrett by small steps offering to talk with publishers in the United States on Machen’s behalf.

The Welsh writer was anxious to capitalize on the interest in his works created by Starrett and others and encouraged him. Machen’s goal was clearly to profit from a new market in the United States.

As a result, Starrett firmly believed he had Machen’s blessing to do both books.

The first page of Starrett’s introduction to The Shining Pyramid.

The first book, The Shining Pyramid, certainly seemed to be designed to please Machen. In his introduction, Starrett writes reverently about his unworthiness to introduce a series of Machen’s early work, gathered from newspaper and magazines published in England.

While some of these early works lack Machen’s more mature vision and writing style, Starrett (who writes as if on bended knee) argues they are worthy of seeing the master at work in his formative years. “He is responsible for the tales and sketches and essays, now for the first time brought together, because he wrote them; but for their appearance in the permanence of covers I alone am to be held to account.”

In an April 6, 1923, letter Machen says he is excited about a “surprise you promise me: money is ever welcome.” The next month Machen writes, “The Shining Pyramid has just come, and as you said it would be, it is a delightful surprise. Your selection is an excellent one, and your preface thoroughly discreet in every respect. … Again, a delightful surprise; and if it runs to a cheque; why that will be a delightful surprise too!”

The confusion is apparent. If Machen knew and authorized Starrett’s actions, why was the volume a surprise to Machen? Didn’t Starrett tell him the details about the project before it was published?

The book, which was copyrighted by Starrett, sold out but its costs left nothing for the author. There would be no cheque for Machen from this book or its successor.

A further complication was a niggling paragraph from an earlier Machen letter, sent in February 1923. “As to the Chicago publisher’s proposition: I believe I am debarred from accepting it by my agreements with Knopf, which bind me to give him the refusal of all new books. But thank you very much for passing on McGee’s very decent offer.” If Starrett was concerned about Machen’s agreement with Knopf, it was not mentioned by him in his 1965 biography or by Murphy in 1977.

Starrett moved ahead with the second book The Glorious Mystery. At first all seemed well.

The Shining Pyramid won over Fanny Butcher’s heart and she praised Starrett’s efforts in her April 28, 1923 Chicago Tribune column. Butcher called it a book of “tales, sketches and essays by Arthur Machen, lovingly gathered together by Vincent Starett who has been these many years a Macheniac, as he calls himself.”

Click on the illustrations below for more.

Machen portraying Dr. Samuel Johnson for a 1922 silent film. From Starrett vs Machen.

Other newspapers noted its publication and urged collectors to get a copy quickly since the limited edition would no doubt soon sell out. The book suffered the same fate as its predecessor: While collectors were willing to shell out $10 a copy, about $160 in today’s currency, the costs of production were such that the author received nothing for the second time in a row.

Machen was furious, as was clear in his May 17, 1924 letter:

“You do not seem to realize the fact that you are a pirate, and that, professing yourself my friend, you are occupied in picking my pocket.”

He goes on to say that he should have protested when The Shining Pyramid came out.

“I did not know this was not so much a detached incident as the beginning of a career. I sign myself for the last time to you, Arthur Machen.”

Then Knopf’s letter hit. Starrett was stunned, as were Covici and McGee. They produced a detailed letter in response, using parts of own Machen’s letters to show he had given Starrett permission to publish uncopyrighted works. Starrett was deeply wounded by the rejection of his idol and wrote a final letter to Machen, saying in part,

“I regret that you found it necessary to write as you did in your last letter. Had I been able to foresee this final chapter, when I penned my first letter to you, back in 1914, I assure you that my admiration would have remained a secret.”

Starrett also wrote to Knopf, citing the permissions that Machen had given him (but leaving out the bit in Machen’s February 1923 letter saying he had to turn down the offers to publish his works, because he was “debarred from accepting it by my agreements with Knopf.”) Starrett demanded a response from the publisher, but never heard back from Knopf, who must have by now realized the situation was hopelessly confused.

A portion of Machen’s April 10, 1924 letter to Montgomery Evans from Arthur Machen & Montgomery Evans: Letters of a Literary Friendship, 1923-47, edited by Sue Strong Hassler and Donald M. Hassler and published in 1994 by the Kent State University Press.

Knopf might be silent, but Machen was not backing down. In an April 10, 1924 letter to his American friend Montgomery Evans, Machen let loose on his one-time disciple:

“I am somewhat troubled by one of your citizens, one Vincent Starrett of Chicago. He has hoisted the Black Flag, and is pirating any thing of mine that he can lay his hands on. I wish you would denounce him whenever and where you can. The title of his latest infamy is The Glorious Mystery. I have no notion as to what it contains.”

Evans was good friends with Richmond, Va., poet Hunter Stagg, who occasionally wrote reviews for The Richmond Times-Dispatch. In a scathing two-column attack in the July 20, 1924, issue, Stagg denounced the books under the headline “Vincent Starrett Takes Poor Way of Showing Admiration by Collecting Relics of Authors Lean and Hungry Days.”

The swipe Stagg takes against Starrett is not limited to Machen’s two books, but includes a third book Et Cetera, also published by Pascal Covici in 1924. For Et Cetera, Starrett selected excerpts from “the flotsam and jetsam” of his favorite writers, which he had pasted into scrapbooks. Starrett felt he was rescuing rare short stories and poems from being forgotten.

But Stagg argues many of these authors should have been asked for their permission or, in the case of their death, deserved a more thoughtful and sensitive editor. He then scornfully addresses the editor’s motives for producing the Machen volumes, saying that Starrett “got all the credit and Mr. Machen all the blame.”

“Mr. Vincent Starrett has proved a poor friend to some of the unfortunate objects of his admiration. The one he has harmed most, of course, is Arthur Machen.”

The material Starrett selected was uncopyrighted, and Stagg says publishing the works were not illegal “although open to question on the ethical side.”

Machen could not have written it better himself.

Click on the illustrations below to see the authorized edition of The Shining Pyramid and Machen’s caustic reference to Starrett in the introduction.

Looking back on it all today, it appears that Machen had been hoping either Knopf or Starrett would be the one who would lead him to a golden American egg and Knopf won. Having a major publisher on board made Machen’s permissions to Starrett a problem that could only be solved by the Welsh writer denouncing the acolyte who brought praise, but no checks.

For his part, Starrett felt betrayed. He had been doing his best but his enthusiasm overwhelmed the care an editor must take with permissions and the compensation of his writers.

In the end, after all the letters had been sent and the stories written, the whole matter ended like a lover’s quarrel where both sides walked away feeling equal parts justified and offended. Starrett still admired Machen’s books, but no longer was his advocate.