“Sally you’re simply great!”

The singular—and single—Case of Miss Sally Cardiff

Long after its first appearance in 1934, “The Bloody Crescendo” was renamed “Murder at the Opera” and then syndicated for daily newspapers. Here is a portion of the full page from The Ottowa Citizen from Sept. 2, 1950.

Miss Cardiff takes the Case

Of all the works I’ve read by Vincent Starrett, I can recall only one story with a female in the lead: observant socialite and amateur detective Sally Cardiff. Miss Cardiff’s one and only outing is also one of Starrett’s most memorable stories, full of good humor and a winning lead character.

A promo for the tale when it went into newspaper syndication, from the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, Feb. 26, 1948.

It is also one of his most frequently anthologized tales, but one that almost no one knows. I hope to change that now.

Before going through its various publications and title changes, here’s a quick look at the story, which first carried the title, “The Bloody Crescendo.” I’ll try to avoid spoilers.

The comely Sally Cardiff and her well-heeled escort, Arnold Carlisle, are attending the premiere of a new opera during a wintry day in 1930s Chicago. They are seated in a box next to the one of Mrs. Emmanuel B. Letts, a matronly member of the city’s well-to-do class. The opera is “The Robber Kitten,” conducted by the one-named Palestrina and featuring his ex-wife, Edna Colchis.

Arnold—who is clearly among the wealthy—is bored, but Sally is thrilled by the crème of society gathered under one roof.

Starrett has lots of fun describing the opera, an avant-garde piece that has something to do with cats.

“The baton descended and there stole through the house the opening notes of the overture to ‘The Robber Kitten.’ A small wailing cry from the violins, quickly abetted by the bull fiddles. The audience shivered deliciously. The cry mounted eerily on little cat feet until it was a strident shriek; then it dropped to the first whispering wail. The crescendo was repeated. It was heard a third time. Then all the violins and fiddles went crazy together and filled the auditorium with harsh, discordant sound.

This continued for some time.”

Arnold was nonplussed, but Sally was thrilled.

Illustration by Paul Norris for the syndicated newspaper version of Starrett’s operatic tale.

“She saw everything,” Starrett tells us. “Everything pleased her.”

Which is part of Sally’s charm. She’s upbeat and seemingly delighted by every new revelation in the case. At one point she muses: “Life was like that. And life was exhilarating—quietly exhilarating.”

At some point during the opera’s first act, Mrs. Letts is murdered, but her famous diamond necklace is not stolen. Since robbery does not appear to be the motive, Chicago Chief of Detectives Dallas assumes a jealous society woman has done the deed. Because who can predict what a jealous society woman would do, right?

Sally isn’t so sure and soon is able to lay her hands on the murder weapon and identify the murderer. Her deductions prove to be correct and the professionals tip their hats to the amateur sleuth with the vigilant eye.

Even her date, Arnold Carlisle, is impressed.

“Sally you’re simply great!” says Arnold as he drives them away from the opera house. “Do you mind if—like good old Watson—I ask one more question?”

And, like Holmes, Sally explains how she deduced the identity of the murderer. Then a very impressed Arnold gushes:

“Do you know, Sally, I think I’m a little afraid of you! It’s rather alarming to contemplate—er—having a detective in the family—er—”

Miss Cardiff blushed a little.

“Don’t be silly,” she said. “They’ll be times when I’ll be grateful for a good old Watson.”

And the two drive off into the snowy Chicago night. The set-up seems clearly made for a series of Sally Cardiff stories.

Sadly, this is her one and only outing.

And it’s a real pity. Unlike other Starrett detectives, for example, Jimmie Lavender, Sally has a strong personality, brains and beauty that set her apart. She’s sure of her observations and intuitions, and uses her looks to make the Chicago detectives listen to her as she tries to prevent them from charging the wrong man.

Another Paul Norris illustration for the syndicated version of Sally Cardiff’s only adventure.

It is also clear that Sally allows Starrett to comment on the male animal in ways that he couldn’t when he was writing a Lavender or Walter Ghost or George Washington Troxell detective tale. Look at how he gives us everything we need to know about snobby Arnold Carlisle:

“His cigar lighter, which he clicked exasperatingly as he talked, was a magnificent affair. It was of gold, by Lemaire, and contained everything but running hot and cold water.”

(Lemaire was a company known for high-society accoutrements, especially their opera glasses and other such flim-flummery.)

In other words, Arnold’s a bit of a toff, but he is obliging and follows eagerly as Sally leads in the chase.

Sally is “getting quite, quite mad.” Don’t worry. She gets better.

With only male police detectives around her, Sally notices things the boys simply would never understand, like the way Mrs. Letts’ long opera glove was ripped from her hand and the dab of rouge that was left behind, which the police mistake for blood.

Most impressively, Sally is clearly able to hold her own against the professionals and makes them stand back as she leads the way.

“By George Miss Cardiff, you are a howling wonder!” Chief Dallas exclaims at one point.

And, like a certain Baker Street detective, Sally tells Arnold she is in this for the sheer intellectual challenge—art for art’s sake, if you will.

“My curiosity is impersonal,” she explained. “It’s just—just curiosity! I really don’t care two straws whether the murderer gets justice or doesn’t. It’s the chase—you know. My wits against his—and both of us against the police. I don’t think I’m morbid, Arnold. As for Dallas—can’t you see him taking all the credit? Why I’ll hand it to him.”

That could be Holmes talking to Watson.

I’ll admit it—I have a little crush on Sally Cardiff. And like those loves who remain a sweet memory forever in our hearts, she is the one who got away.

A Start in the Pulps

Which is not to say that her one and only adventure is obscure. Quite the opposite.

As I mentioned earlier, Sally Cardiff’s night at the opera is one of Starrett’s most frequently repeated tales.

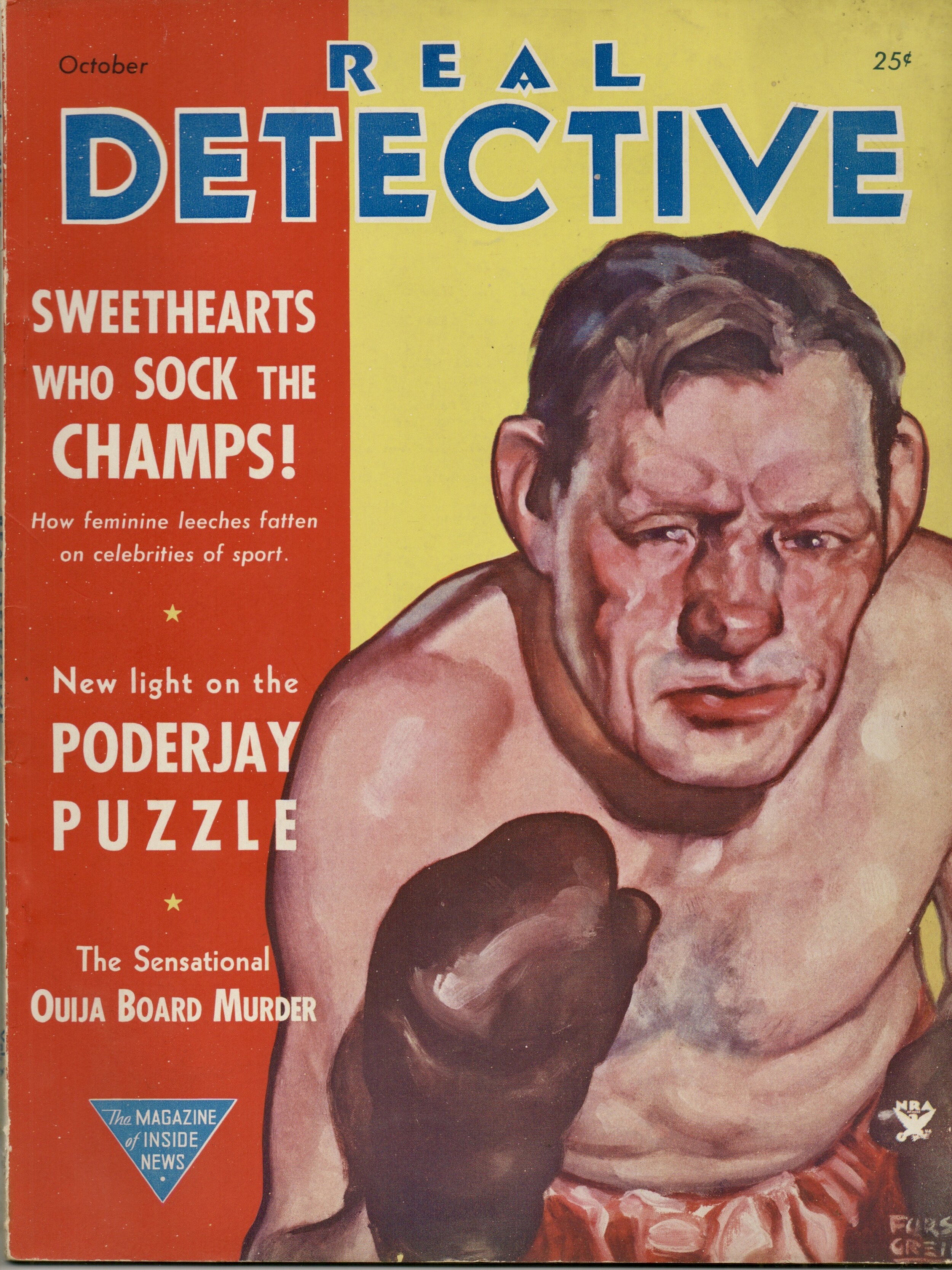

It all started in an issue of Real Detective magazine for October 1934, featuring the punch-drunk palooka on the cover next to the screaming headline, “SWEETHEARTS who SOCK the CHAMPS!: How feminine leeches fatten on celebrities of sport.”

Subtle this cover is not.

There were only two fiction pieces in this issue, Starrett’s and “The Leaping Corpse,” a Frankenstein-ish tale by Edward S. Sullivan.

Starrett’s story starts at the middle of the magazine and quickly jumps to the back pages. Originally titled, “The Bloody Crescendo,” it was also one of the last of Starrett’s detective stories to appear in Real Detective, which was shifting its content increasingly to lurid stories ripped (and embroidered) from the day’s headlines.

Features like “Nudism in the National Capital”—with illustrations no one should have to see and “Why Mrs. Antonio Had to Die at Sing Sing” were replacing the fictional tales of detection like those written by Starrett.

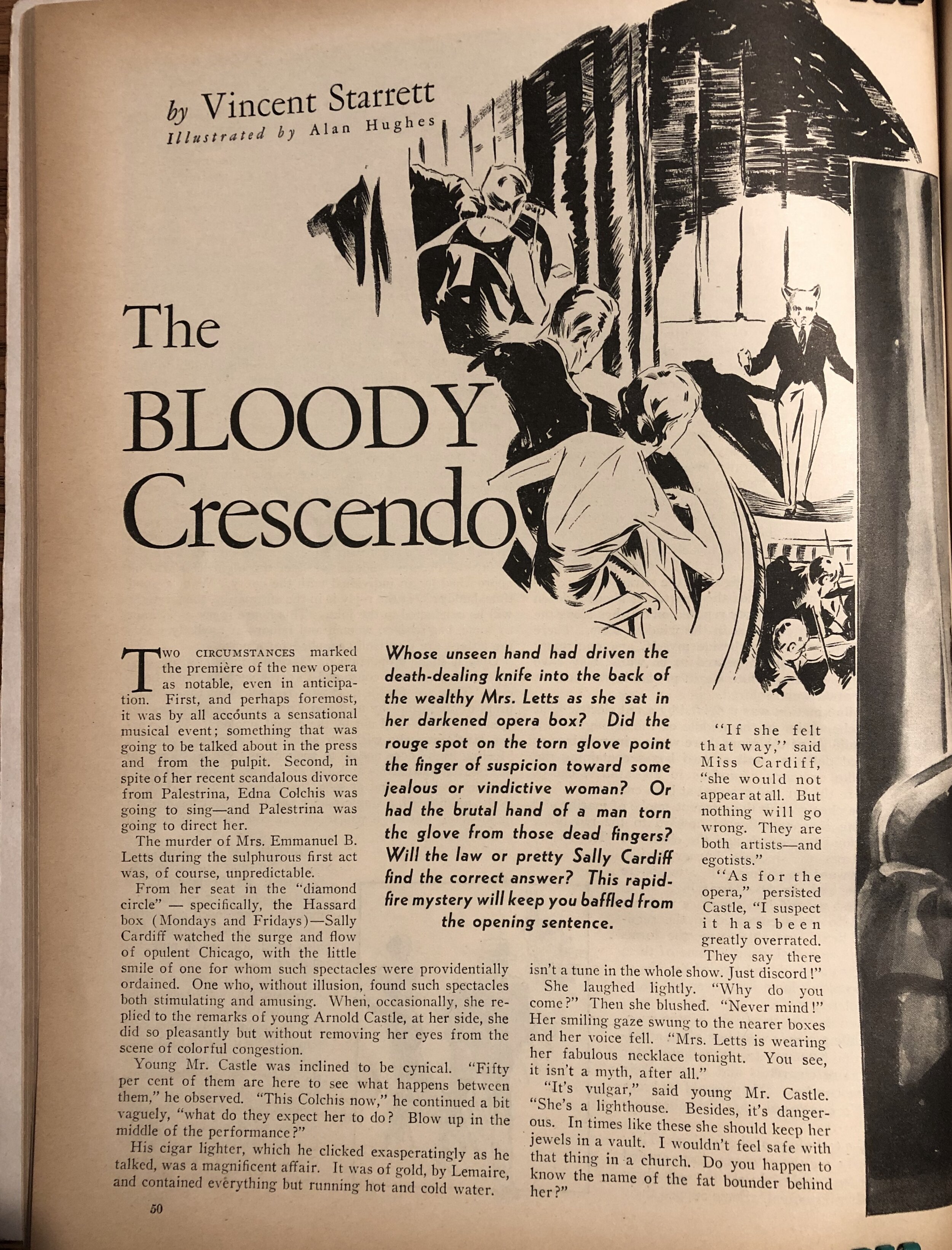

I want to take a moment to talk about the original illustrations for this tale. Alan Hughes is credited with the two drawings. The opening line art on page 50 shows the backs of Sally and Castle in the foreground, and Mrs. Letts with her opera glasses raised to the left. Onstage is the famed tenor, Orlando Diaz as Grimalkin, the lead character from that night’s opera, “The Robber Kitten.” It’s a nicely done set piece showing us the scene shortly before Mrs. Letts is killed.

But the real gem here is the next illustration, a wash drawing that shows Sally Cardiff looking somberly puzzled, Castle being more serious and involved than the text might imply, and Mrs. Letts slumped forward in death. It’s an emotional scene that, surprisingly, was not played for its full shock value: Note that Mrs. Letts does not have a knife protruding from her back. In all, it’s a satisfying work and shows Hughes’ distinctive ability to capture a moment.

This isn’t the only time Alan Hughes’ work overlapped with Starrett’s in Real Detective.

Hughes also did the cover for the April 1933 issue, which promoted Starrett’s “Complete Novelette” near the bottom of the page.

Before we leave Real Detective, I need to admit it was a shock to discover that this was a two-part story, with the final part in the November issue, which I have yet to add to the collection. I have seen images from that issue courtesy of a member of the Golden Age of Detection Facebook page, and those illustrations are again by Hughes and equally handsome. Can’t wait to get my own copy.

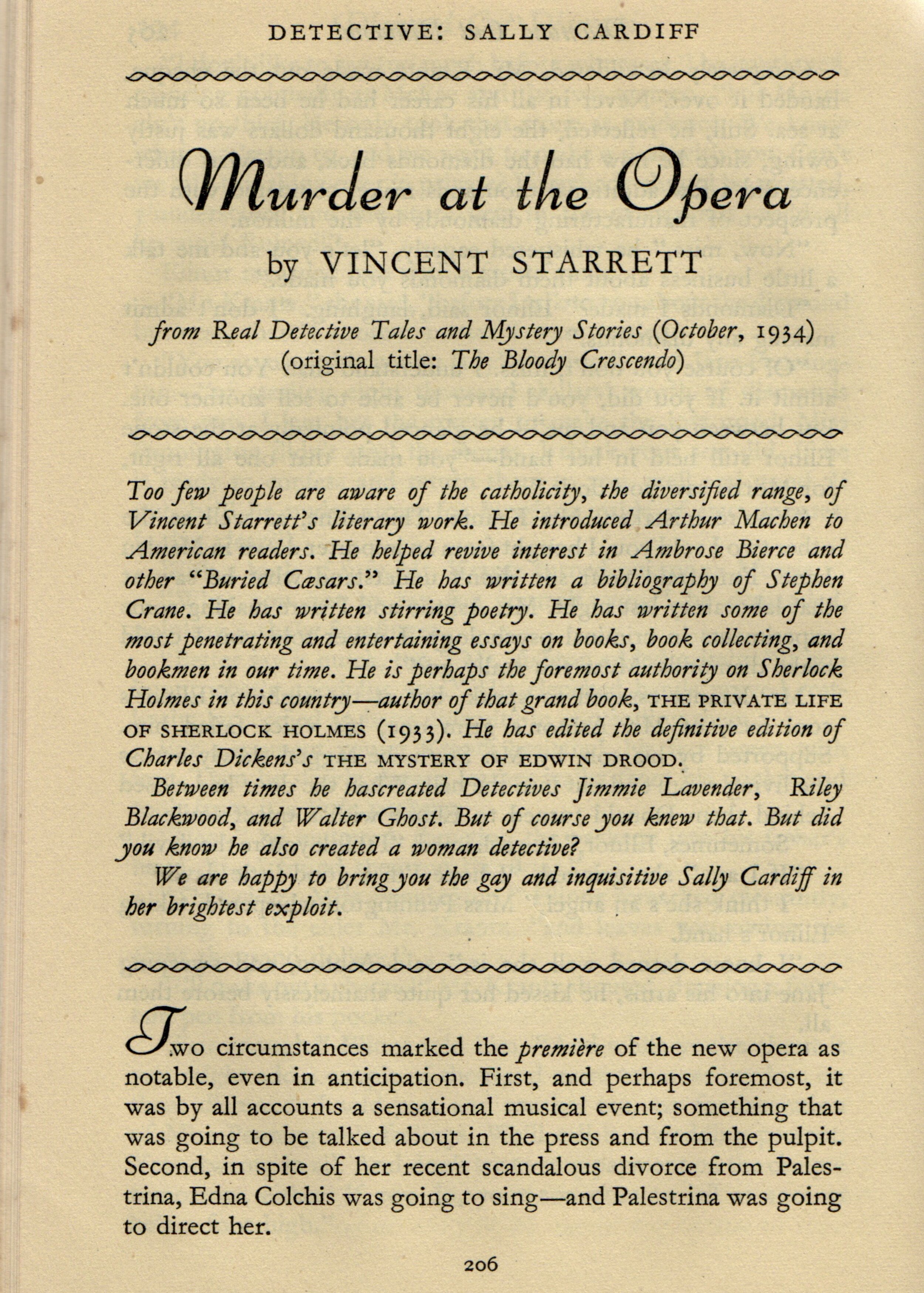

On to the Digests

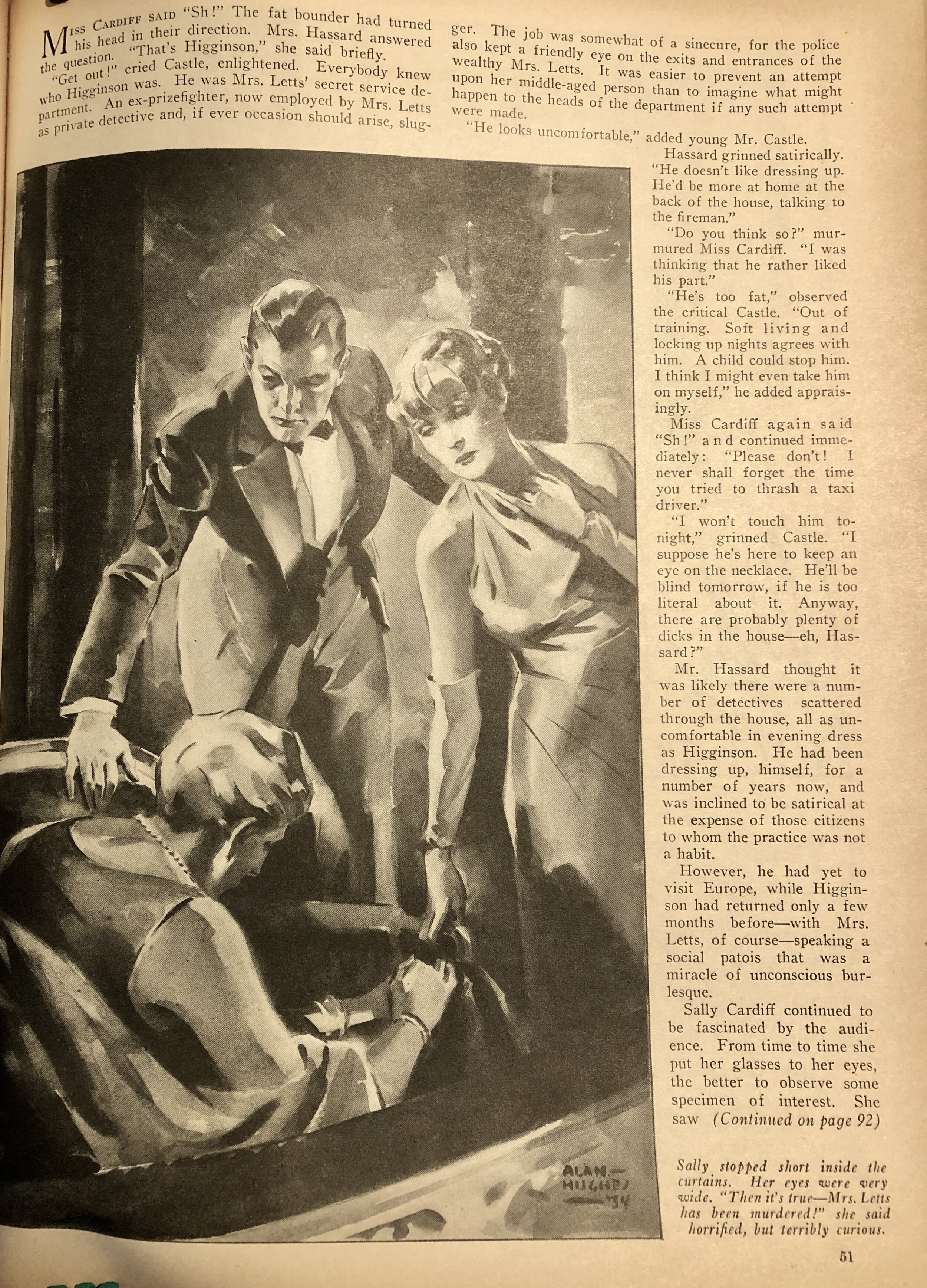

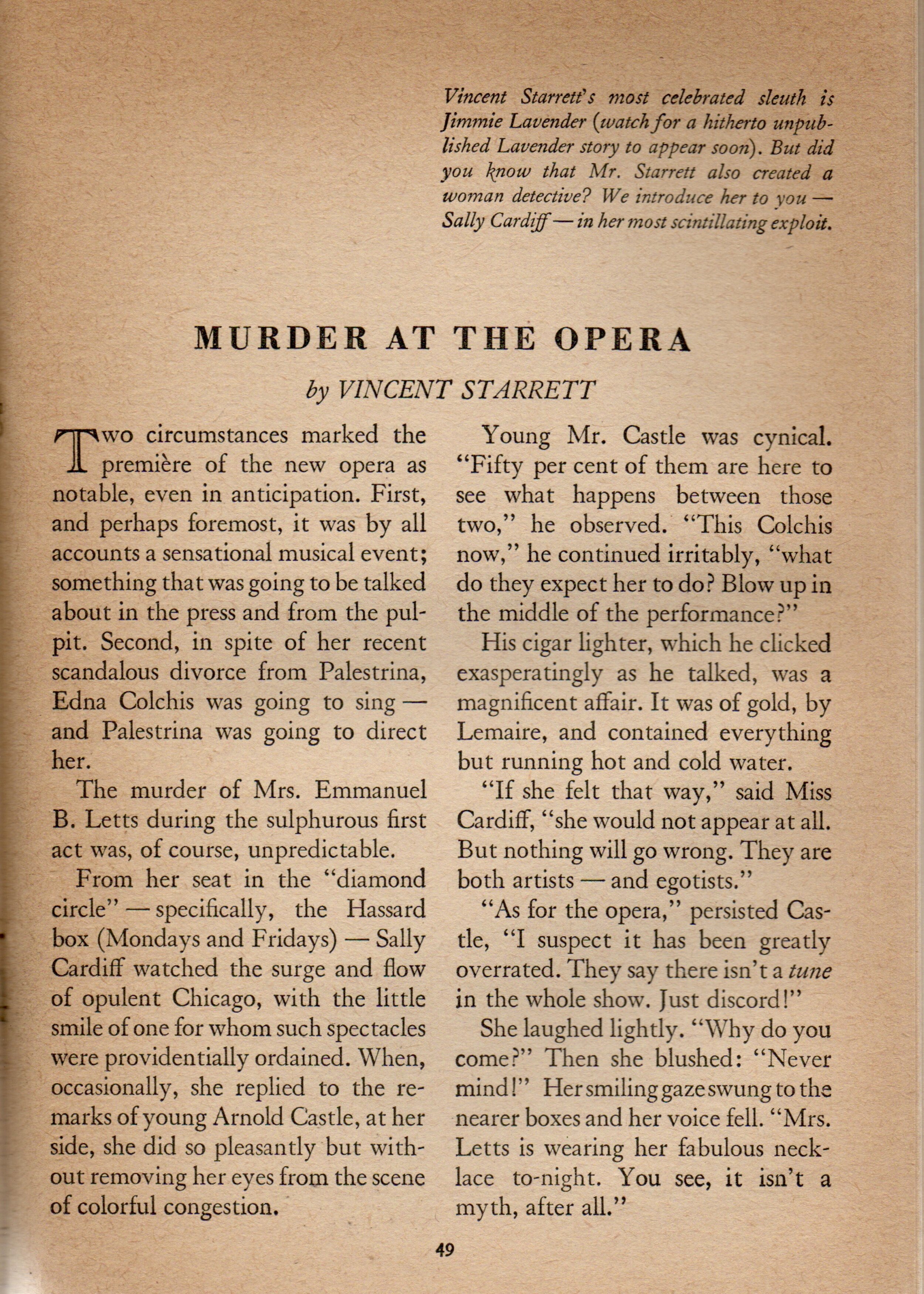

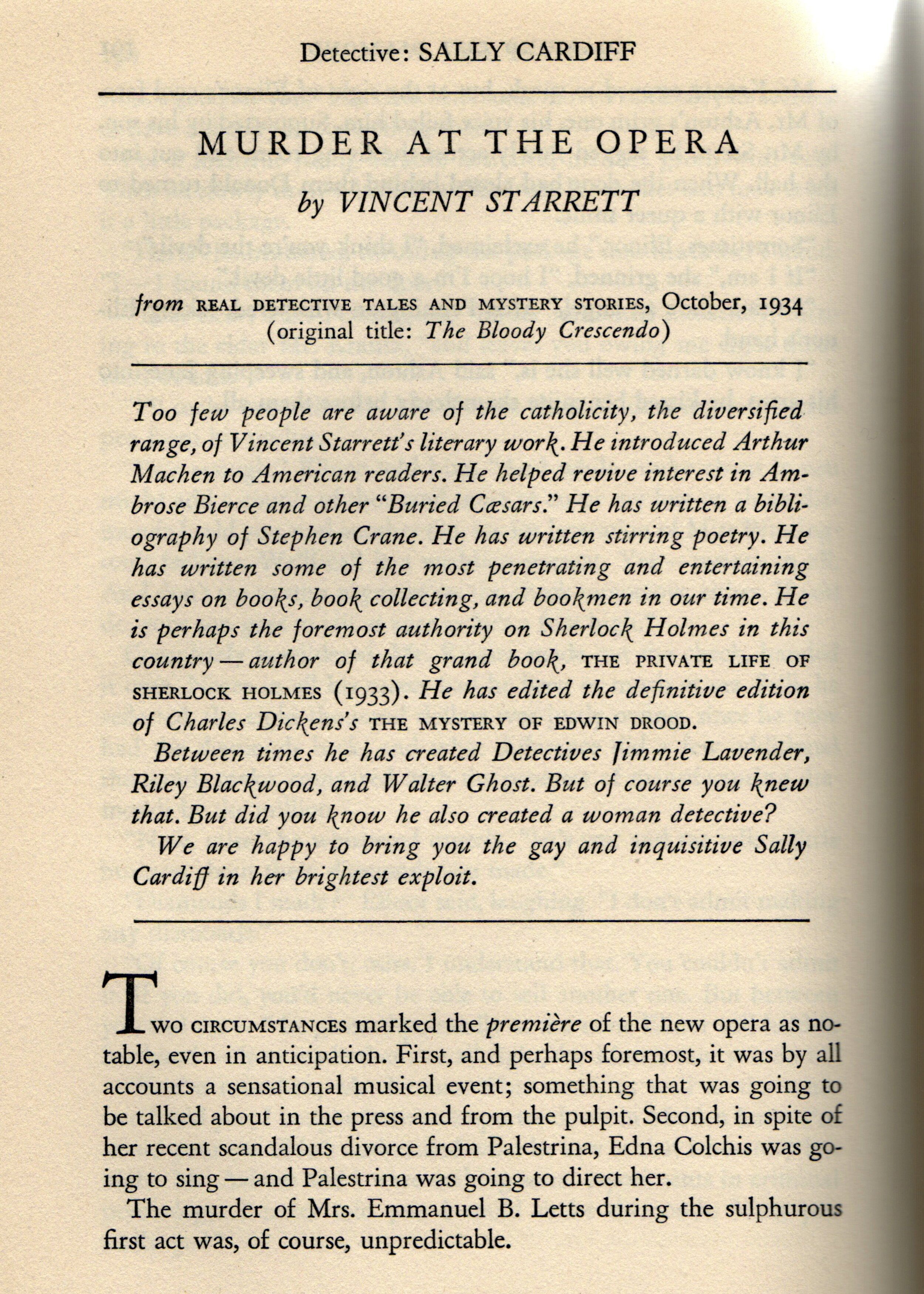

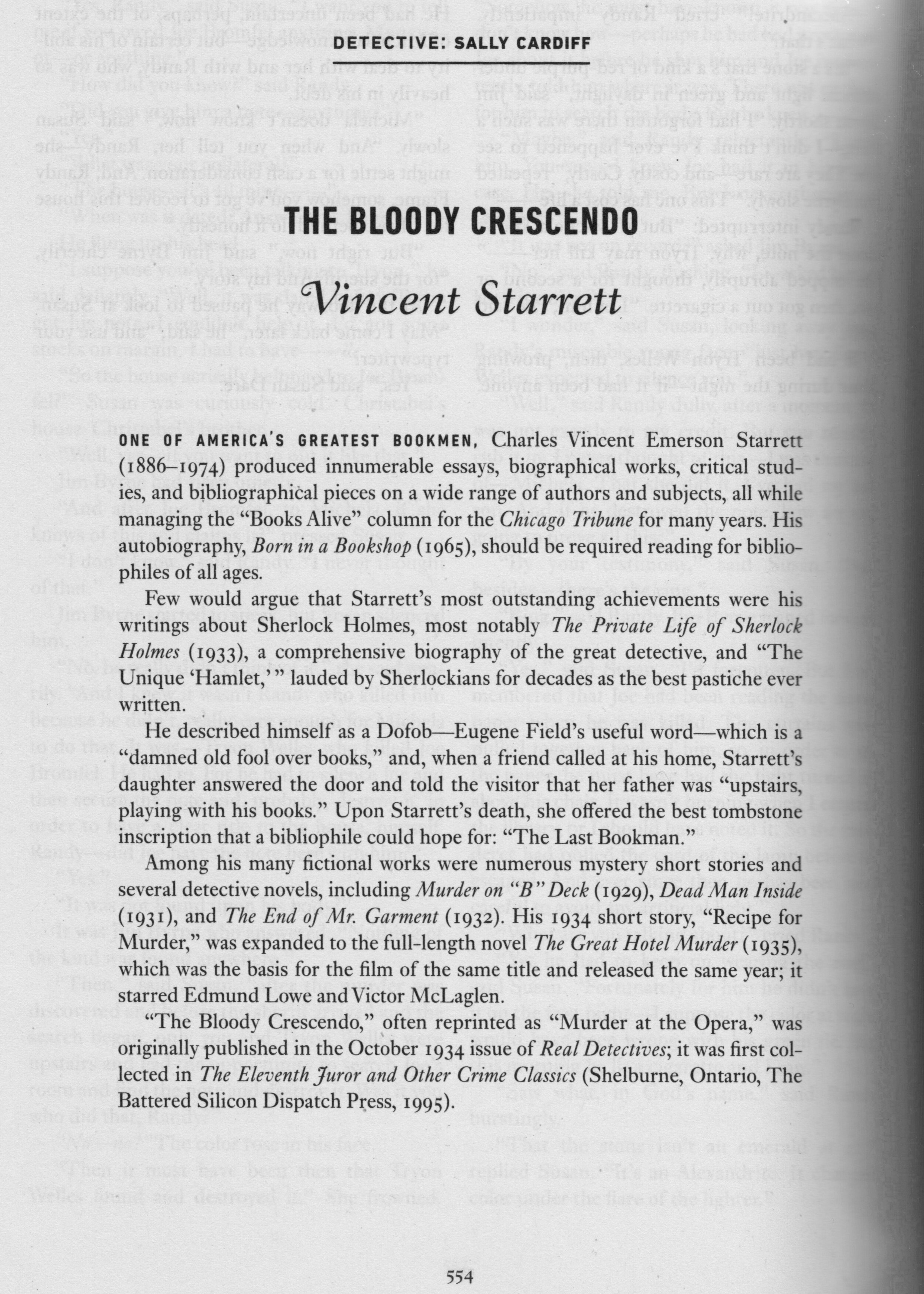

Nine years later, as Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine was gathering steam, Starrett’s story was reprinted in the May 1943 issue with a new title: “Murder at the Opera.” Several of Starrett’s stories from earlier decades found a home in EQMM, and if it was fellow BSI Frederic Dannay who wrote the introduction, it was clear he was happy to have this contribution.

“Vincent Starrett’s most celebrated sleuth is Jimmie Lavender (watch for a hitherto unpublished Lavender story to appear soon). But did you know that Mr. Starrett also created a woman detective? We introduce her to you —Sally Cardiff— in her most scintillating exploit.”

This is not only Sally’s “most scintillating exploit,” it was her only exploit.

Who knows, maybe Starrett told Dannay that Miss Cardiff—like Mr. Lavender—might return for a future issue of EQMM?

Between Hard Covers

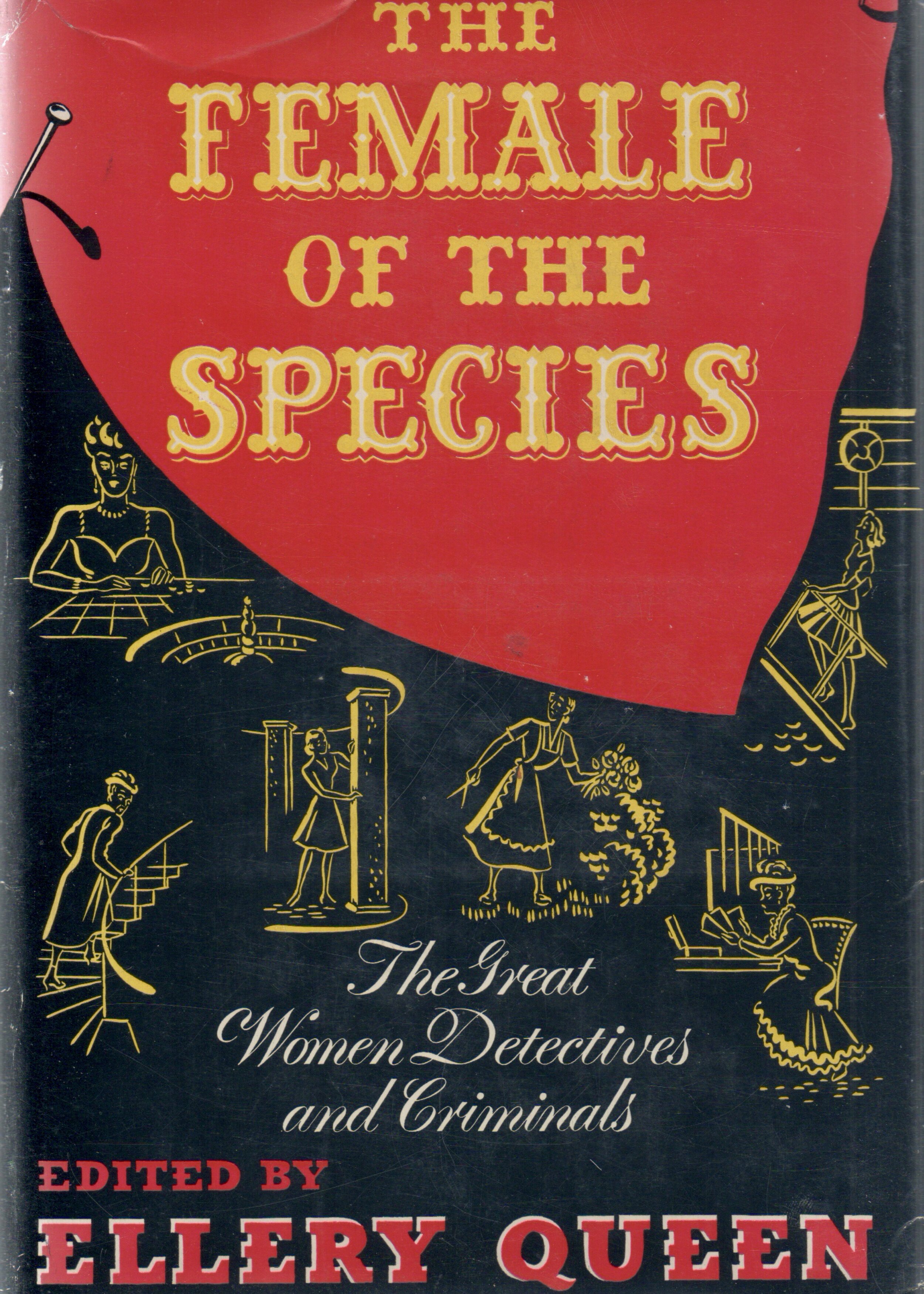

Speaking of Ellery Queen, he once again reprinted Miss Cardiff’s “most scintillating exploit” in an anthology entitled The Female of the Species: The Great Women Detectives and Criminals.

Published in July 1943 by Little Brown & Company, the story has excellent company, rubbing shoulders with contributions by mystery regulars like Paul Gallico, Mary Roberts Rinehart, H.H. Holmes (aka Anthony Boucher), Agatha Christie, Baroness Orczy, Fergus Hume, John Kendrick Bangs (writing a tale of Mrs. A.J. Van Raffles) and Edgar Wallace.

At a time when the field was dominated by men, Queen’s decision to produce an anthology of stories featuring females was seen as a progressive move. The fact that most of those stories were written by men, not so much.

Like the other authors, Starrett received a more fulsome bio, as you can read in the accompanying illustrations.

The book also had a British edition that same year but with a different title: Ladies in Crime: A Collection of Detective Stories by English and American writers, published by Faber and Faber Limited of London.

In New York, they were “females.” In London, they were “ladies.”

Dust jacket design is not my forté, but why in heaven’s name did Faber and Faber decide that the best way to illustrate the cover was to print the title SIX TIME? What a remarkable lack of imagination.

And one assumes the pink background color was selected because we are, after all, talking about ladies.

Oh brother.

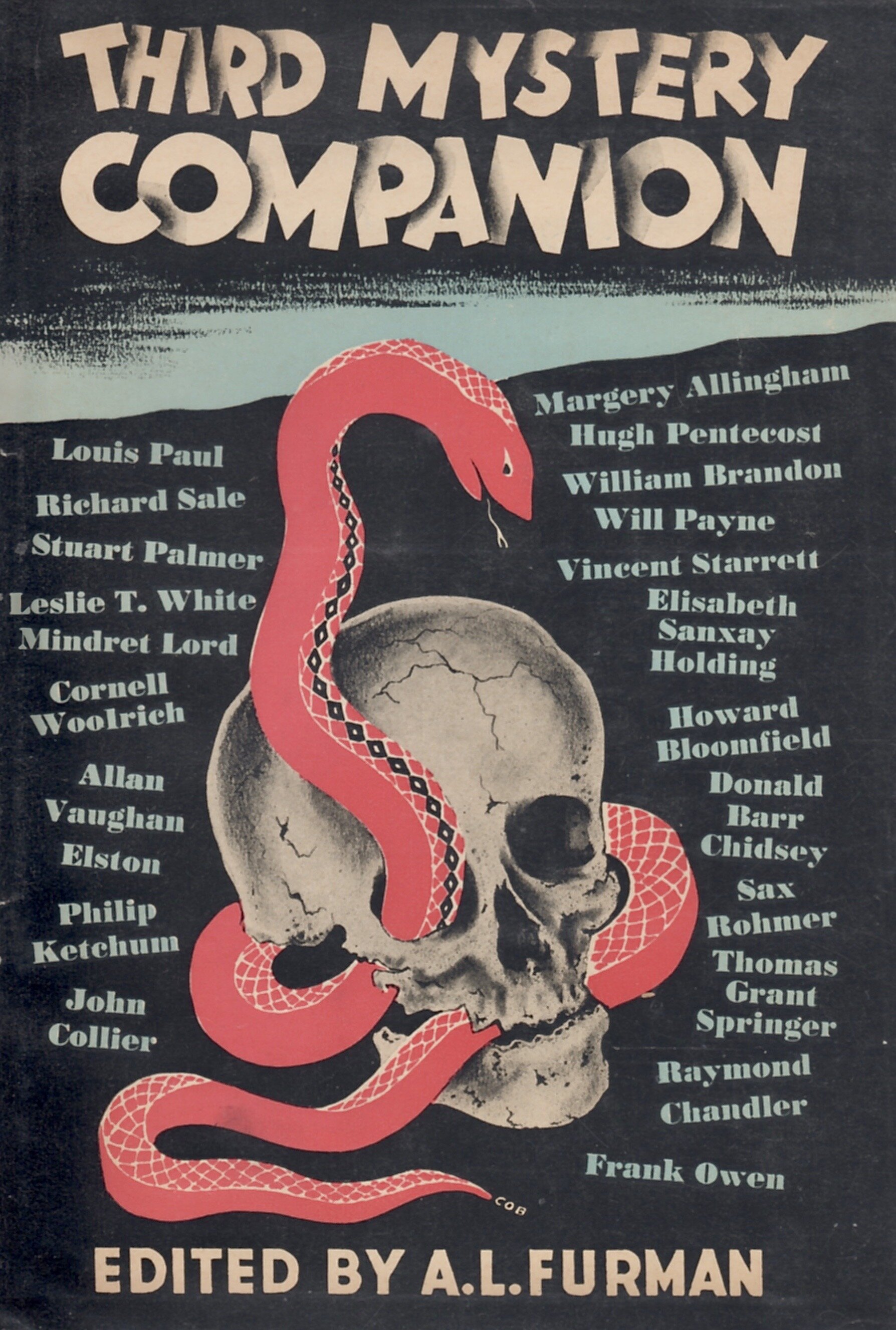

One more book to add before returning to the mystery digests. In the 1940s, Gold Label Books in New York published a series of Mystery Companions anthologies reprinting some of the best stories of the last few decades. There were four volumes in all edited by A.L. Furman, and Starrett had stories in each.

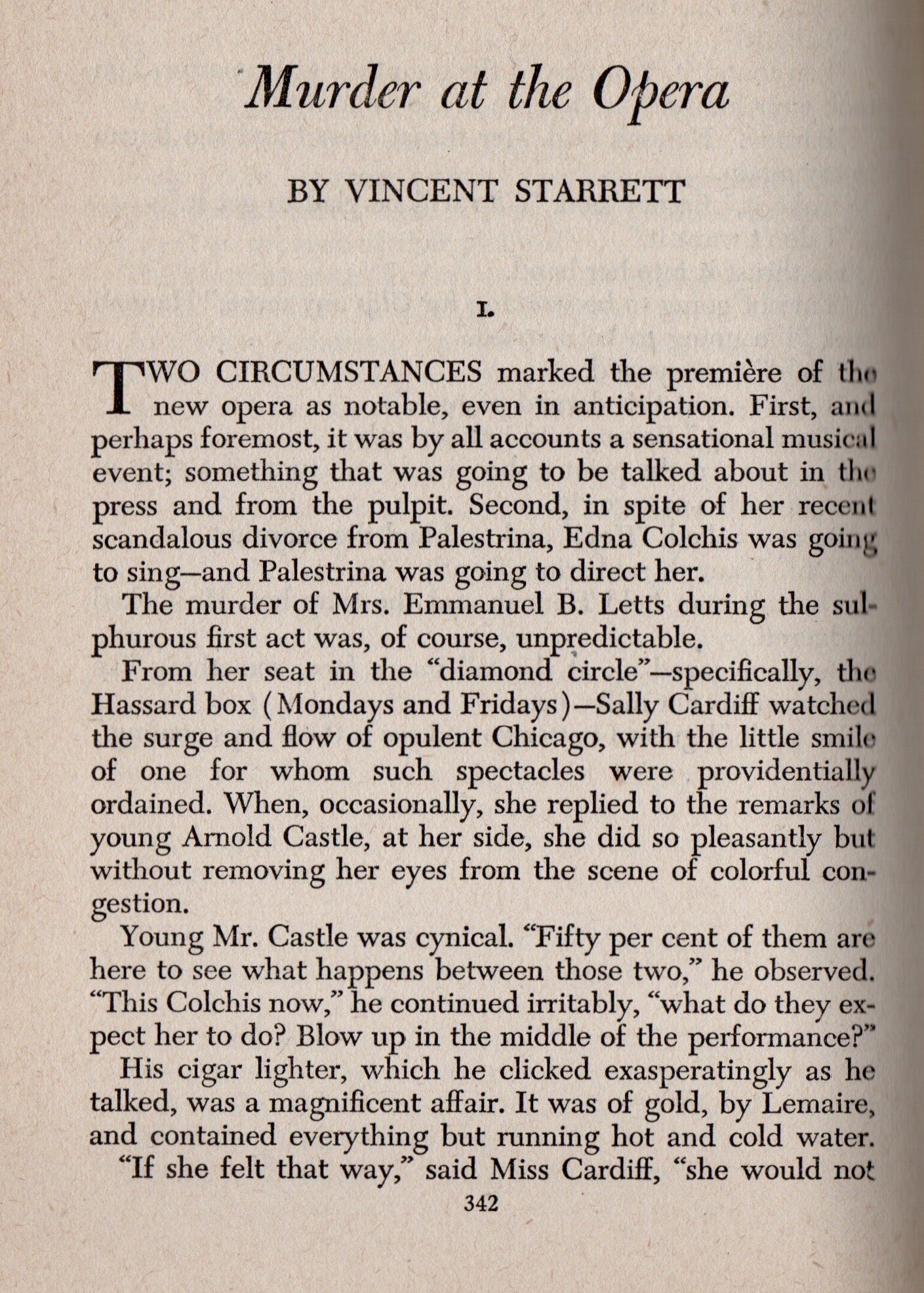

When this post first went live, it didn’t include this entry, because I had forgotten it. Regular reader Dan Andriacco reminded me that Sally Cardiff’s sole adventure made it into The Third Mystery Companion, published in 1945. “Murder at the Opera” was the final tale in the book.

Here’s the creepy/fun dust jacket for the volume and the first page of Starrett’s story.

Thanks Dan!

If you have time, drop over to Dan’s Baker Street Beat blog, where he occasionally talks about Starrett and always has something worthwhile to say.

Back to the Digests

Is that Mrs. Letts about to be stabbed?

Miss Cardiff was still far from retirement.

She popped up in an Australian issue of Short Story Magazine in February 1947—another title I have yet to run down, and one that will likely never grace my shelves. That makes me sad.

Sally’s next American revival was in the eighth issue of Rex Stout’s Mystery Magazine, published in May 1947.

I’m tempted to say that’s an illustration of Mrs. Letts being murdered on the cover. That could be an expensive opera box circa 1934 in the background. But the woman being threatened is not wearing a necklace, a fact which is obvious for anyone glancing at her, ahem, neckline.

Add to this the fact that the fellow with the knife doesn’t match the description Sally gives us of the killer and it seems less likely.

But after going through the other stories in this issue, I can report the illustration doesn’t match anything else either.

A Round of Newspapers

The Racine (Wisc.) Journal-Times gave Sally a full page to show her stuff on Dec. 19, 1954.

Sally’s next return took place not in a magazine or a book, but in a series of daily newspapers over several years. Like a few other Starrett tales, “Murder at the Opera” was syndicated by King Features. It would not have paid the author a lot, but it was a paycheck for no new work, and it kept his name in front of the public, which is worth it. I have found a couple of examples, featuring the evocative artwork of prolific illustrator Paul Norris, best known for his influence on the first incarnations of Aquaman and Sandman for the comics.

The King Features syndication seems to have had a couple of runs. I’ve found it in the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph in February 1948, The Ottowa Citizen in 1950 and again in the Racine (Wisc.) Journal Times in December 1954. I’m sure there were other examples.

Back to Books

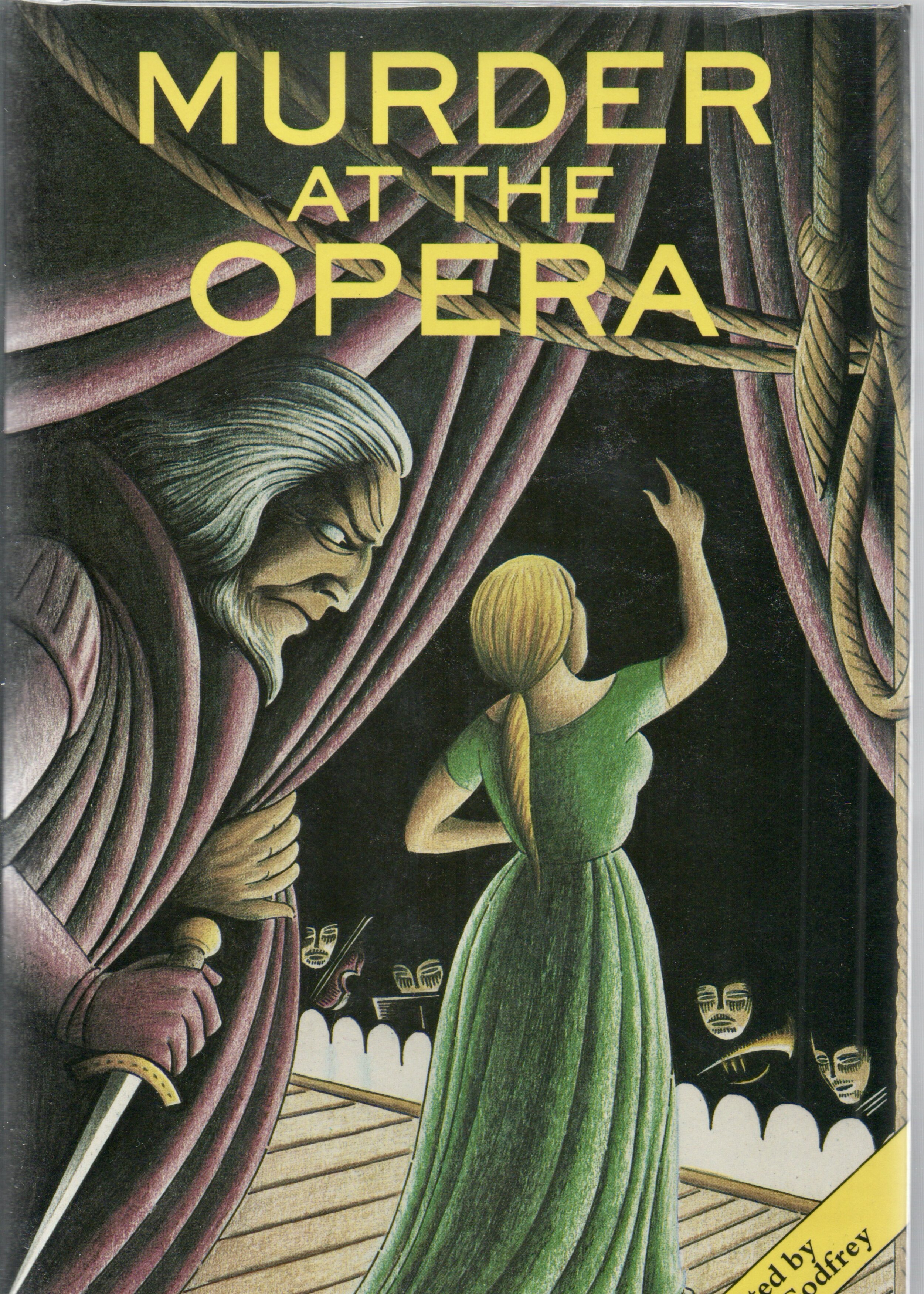

Sally had a great hiatus until 1988, when she returned to print on both sides of the Atlantic in Murder at the Opera, which carried the unnecessary subtitle: Great Tales of Mystery and Suspense at the Opera.

Edited by Thomas Godfrey, it was published by Michael O’Mara Books Ltd., in London. The next year, the same book was given The Mysterious Press imprint when it appeared in 1989 in the U.S.

In his general introduction, editor Godfrey gives the tale it’s third title, calling the story “A Box at the Opera.” It’s a title I had not seen before, and I think it’s a mistake, because it doesn’t even carry over into the rest of the book. In the book’s index and the on the story’s first page, the title inexplicably reverts back to “Murder at the Opera.”

But wait, there’s more!

In December 1995, Peter Ruber included “Murder at the Opera” in Volume 6 of The Vincent Starrett Memorial Series in the volume titled The Eleventh Juror and Other Crime Classics, published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box press.

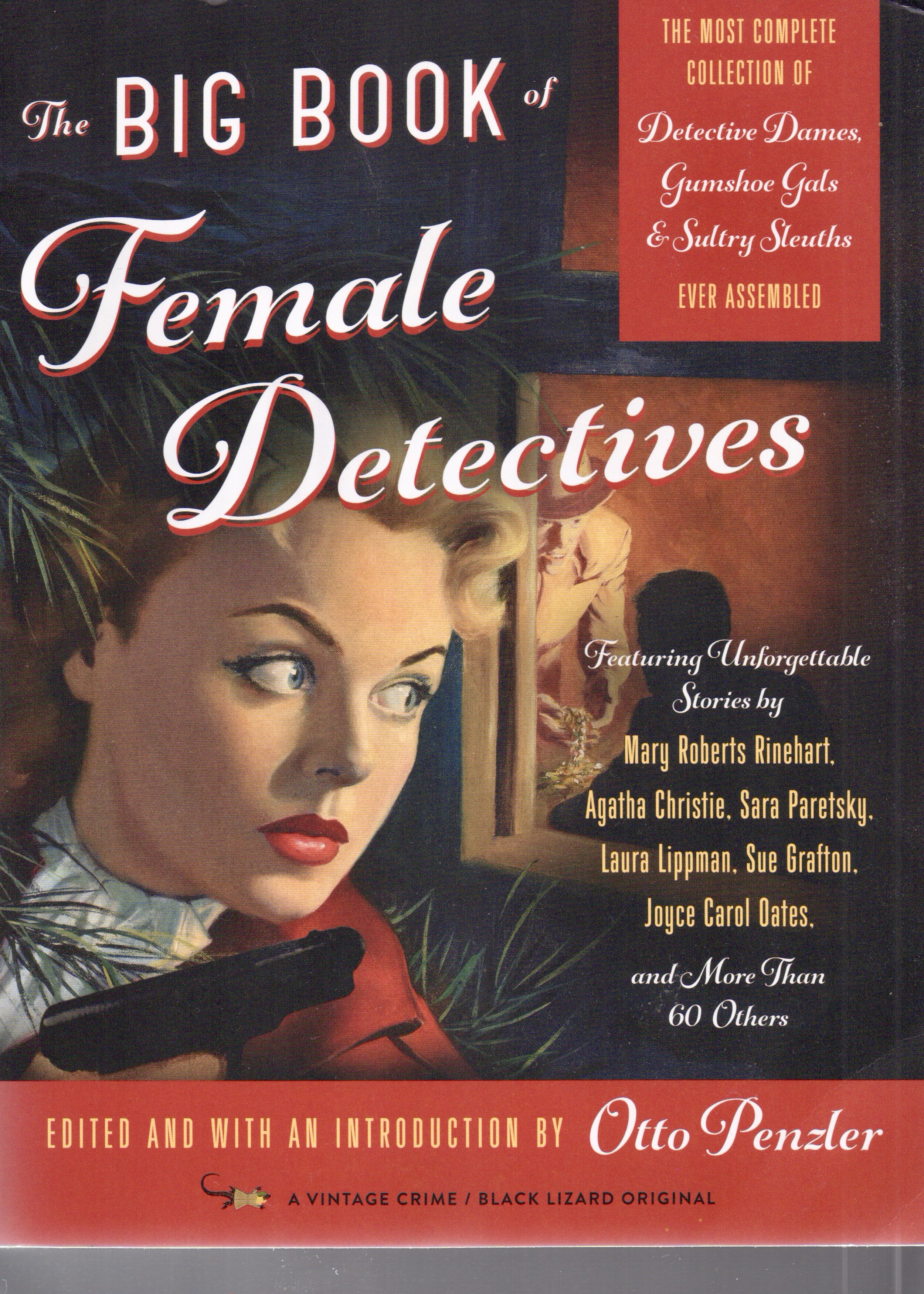

Finally, in October 2018, Otto Penzler of the Mysterious Press picked Miss Cardiff for one of his big reprint books, this one called The Big Book of Female Detectives. Otto returns the original title to the tale, “The Bloody Crescendo.” He also offers a loving tribute to Starrett in the introduction.

As you now know, Miss Cardiff may have had only one outing, but she’s had a very full reprint life indeed.

Sally’s Role Model?

And as we sign off, here’s a bit of speculation.

Vincent Starrett and Ray. Was she the model for Sally Cardiff?

Most of Starrett’s detective heroes are variations on himself or friends: Jimmie Lavender, Riley Blackwood and Walter Ghost all have some characteristics that align with the author. Obviously, Sally is an exception. So where did she come from?

In the early 1930s when this story was written, Starrett had been separated from his wife Lillian and had deeply fallen for Rachel (Ray) Latimer. We don’t get much of a physical description of Sally Cardiff, except that she is petite, attractive and has beautiful eyes.

Could Starrett have patterned his only female detective after his new love? And could the blushing dialogue between Sally and Arnold quoted above be an echo of the flirtiing between Vincent and Ray?

It would help to know if the cigar-smoking Starrett ever owned a lighter by Lemaire.

I like to think so.