Walking with Old Glory

Sgt. Bates and Mr. Starrett

In 1938, Vincent Starrett needed money. He and Ray had just returned from their two-year trip around the world and Starrett had burned through the money he made from selling The Grand Hotel Murder plot to Hollywood.

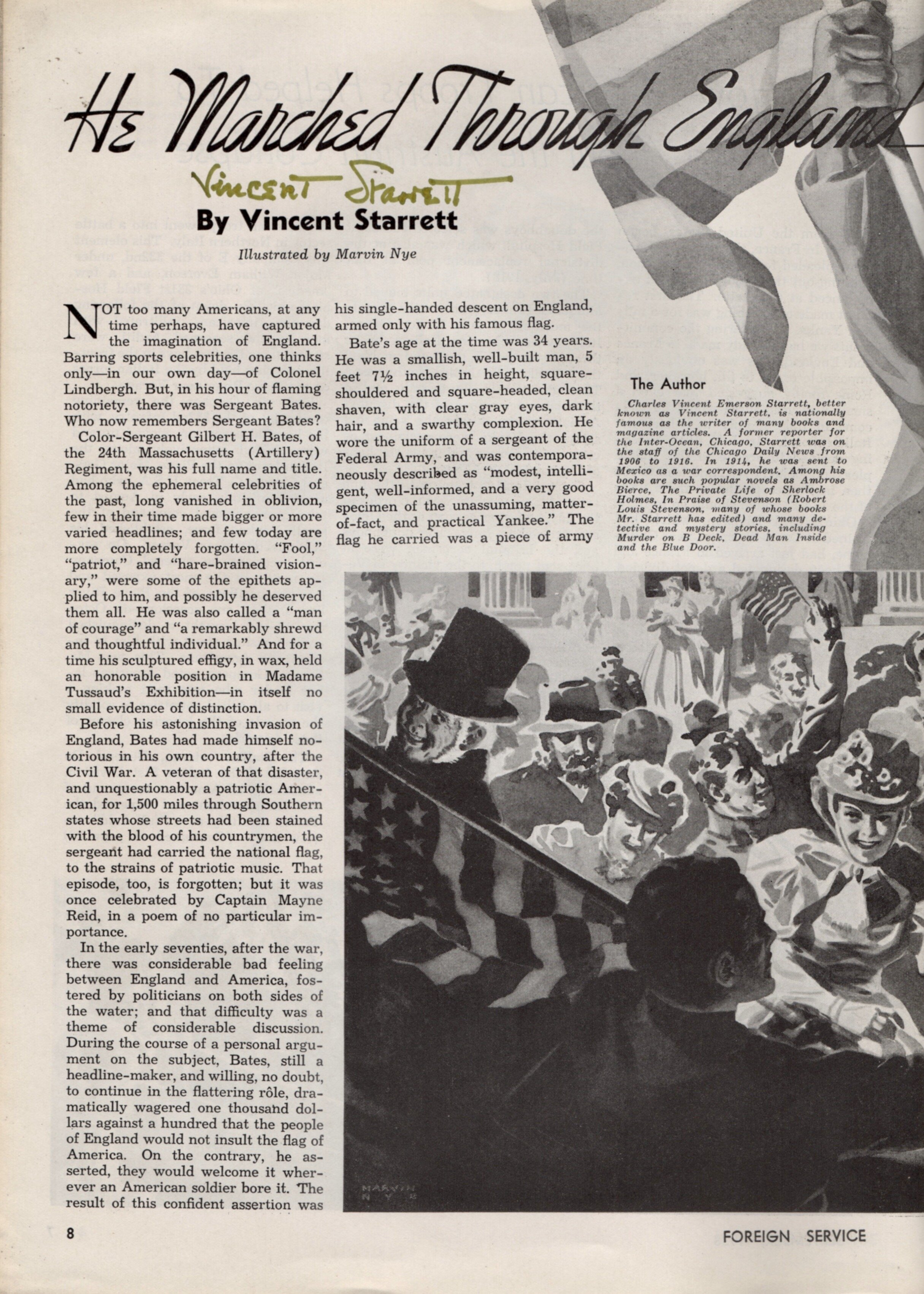

He hit the typewriter and started writing anything and everything that would bring in quick cash. That’s why he wound up editing A Modern Book of Wonders, and why he recounted the tale of a flag-waving Civil War veteran for the September 1938 issue of Foreign Service magazine.

Sgt. Bates. Photo from Wikipedia. More here.

I knew nothing about this essay until a copy of Foreign Service came up for sale on eBay. The sexist cover didn’t excite me, but the Starrett piece on the inside was intriguing. (By the way, I am skeptical of that Starrett signature above his name. It looks like it was done in felt tip pen. The vast majority of authentic Starrett signatures were done with him using a fountain pen. Felt tip pen signatures tend to be the work of another hand.)

The small block of biographical copy is also a little off, especially this sentence: “Among his books are such popular novels as Ambrose Bierce, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, In Praise of Stevenson (Robert Louis Stevenson, many of whose books Mr. Starrett has edited).”

Portrait of Sgt. Bates.

First, none of those three books are novels. Ambrose Bierce is an extended essay/appreciation of Bierce’s work and impact; you should know what The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes is all about; and In Praise of Stevenson is a festschrift in verse.

There is not a novel in the bunch.

Second, Starrett edited a single book of poems praising Stevenson, but that’s far from editing “many of” Stevenson’s books themselves.

Aside from that, the sentence is fine.

But I digress.

As I was saying, I was intrigued by the tale of a Civil War soldier who marched through England carrying Old Glory, in order to disprove the belief that the British were completely on the side of the Confederacy during the American conflict and would not respect the Union flag. The soldier in question was one Sergeant Gilbert H. Bates, and as Starrett notes, his march through England would actually be the second of its kind.

Here’s a look at his first march.

In 1868, with the re-United States still licking its wounds from the Civil War, there remained a wary association between the Northern and Southern states. Bates believed there was more respect for the Union in the South than most Northerners thought. So he decided to march in uniform from Vicksburg to Washington DC with Old Glory. His audacity was matched by the mounting publicity that grew around the stunt.

A full-page story from The ( Madison, Wisc.) Capital Times of April 22, 1982, recounting Sgt. Bates’ march through the former Confederate states.

Newspapers carried daily reports of his progress, of his reception among farmers and townsfolk. Bates was received with respect and as a hero of sorts. Although his efforts during the war warranted little notice, his march through the South came to symbolize the potential that a re-unified United States could heal itself over time.

Sgt. Bates marched through Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina and Virginia to Richmond, the heart of the Confederacy, still reeling from the war’s devastation. Perhaps because he was not a leader of the army, but an enlisted man like so many others, townsfolk celebrated his arrival, put him up in local homes, fed and entertained him, and sent him on his way with praise and cheers.

Former Confederate soldiers sang songs and shared whiskey. Farmers offered food from their fields and one former rebel solder took him to the grave of his brother who died during the war. Standing on opposite sides of the grave, the two men reached across and shook hands.

“Will any one say that I did wrong in taking the hand of one against whom I had fought, but who now was willing to stand by the old flag and bury the differences of the past?” asked Bates in his tale of the journey.

A few years later, Sgt. Bates accepted a wager that he could not conduct a similar march through England with similar good will. The result, as Starrett records, was a spectacular journey that duplicated his reception through the American South. “At whatever town or village he put up he was given an ovation, and the enthusiasm gathered volume as he neared his journey’s end.” Starrett reports. “News of his coming always preceded him, and there can be little doubt that his progress was a continuous triumph.”

The rare pamphlet chronicling Bates’ marches across the American South and England.

His entry into London caused traffic jams and so much disruption that the Sheriff of the Old City offered Bates an open-air carriage so that he could proceed without being trampled by the crowds. On Dec. 1, 1872, he rode up Notting Hill and along Bayswater Road, Bates and his flag up front followed by the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes trailing behind.

(Starrett fails to note that this part of the journey anticipated the sentiments of Sherlock Holmes, who hoped that one day the two nations would exist under “a flag which shall be a quartering of the Union Jack with the Stars and Stripes.”)

The procession to the Guildhall was festooned with the flags of both nations and the good sergeant reached his destination, he was paraded up and down the street on the shoulders of well-wishers.

Bates had long ago repudiated the wager, saying his reception among the British was its own reward. But his fame didn’t end with the march.

Seeing an opportunity, the good folks at Madame Tussaud’s Exhibition (just a short turn from Baker Street) asked for and received his boots and a piece of his flag. His likeness was soon carved in wax and put on display for several years. John Theodore Tussaud, in his 1921 history, The Romance of Mrs. Tussaud’s, dedicated two full chapters to Bates’ march and enshrinement in the museum.

And there the matter would rest for Bates, Tussaud’s and Starrett. Until Valentine’s Day, 1943.

A portion of Starrett’s “Books Alive” Feb. 14, 1943 column for the Chicago Tribune.

Writing in his still-new “Books Alive” column for the Chicago Tribune on Feb. 14, Starrett noted that someone had asked for information about Bates in American Notes and Queries (“A Journal for the Curious”).

Starrett recalled that Bates had at one time been a household name on two continents, but had fallen into anonymity after his two marches.

“Bates was the champion headline maker of his little day,” said Starrett. “What cynics said about him, in that day, was plenty; but it is possibly true that he attempted something for international amity. … It is an odd business, the thing called fame. Who would have thought, 70 years ago, that Sgt. Bates ever would be forgotten? Certainly not Sgt. Bates.”

Thanks to Starrett, a bit of Bates’ life story lives on.

Happy Flag Day everyone.