One of "My Disciples," Part Two

A Vincent Starrett Library By Charles Honce

Title page to Honce’s bibliography of Starrett’s work.

Last time out, we talked a bit about Charles Honce, the Associated Press reporter and editor who became one of Starrett’s “disciples.” This post is dedicated to Honce’s invaluable bibliography, which was compiled with Starrett’s help and occasional comment.

The Guide

Contrary to the impression I give, I have not always been a Vincent Starrett collector. I accumulated books by him off and on over the decades without any real thought or pattern. If I saw a copy of one of his mystery novels—battered and lacking dust jacket—for $5 in a library sale, I would buy it, read it and shelve it.

I picked up a few better editions of his Holmes works (like the various editions of Private Life), but otherwise my Starrett collecting was aimless.

Then, about 15 years ago, I came across a copy of Charles Honce’s book, A Vincent Starrett Library: The Astonishing Result of Twenty-Three Years of Literary Activity. It was a pricey volume and I took a pass on it the first time around, only to go back later to purchase it. It was, at the time, the most expensive book relating to Starrett that I had ever purchased.

Suddenly, I had a mission: Try to hunt down as many pieces in the bibliography as (practically and financially) possible and make them part of my own library. It was an intimidating thought, but I dove in knowing I was not alone. In Charles Honce, I had a friendly guide—someone I never met but who left this book as a roadmap. The search for Starrett treasure was on!

I’ve taken on this pursuit despite the warning Honce gave readers in this thin, handsome volume.

‘These 129 Odd (Great God!) items’

Unlike Peter Ruber, who titled his homage to Starrett The Last Bookman, Honce uses this essay to discuss the ethereal nature of Starrett’s imagination.

Here’s what he says about his own collecting challenges in his prefatory essay, titled “The Last Romantic:”

“I’ve been collecting Starrett firsts for quite a few years. . . . I have been amazed at the number of things I have turned up. And, while my collection already runs to rather startling proportions, I haven’t the slightest idea that I’ll ever be able to get together all of his missing numbers. Not in this lifetime, at least.”

That sounds familiar.

For his own part, Starrett was both honored and embarrassed by Honce’s work, as he pointed out in a closing essay, “A Backward Glance.”

It is not every amateur of letters who has a book written about him—even a slim volume limited to one hundred copies—or such a friend as Honce to write and publish it. Obviously, the whole episode is flattering. . . . However, it does put me on the spot. Looking over the record of my labors — these 129 odd (Great God!) items connected with my name — I find myself filled with a wild desire to apologize and explain. But to whom and for what?

Early in his life, Starrett put together bibliographies of Stephen Crane and Ambrose Bierce. Now, to have one done of his own work, he was “dismayed to discover how little I have done that has any chance of survival and how much I have done that is trivial and inferior.” He admits to wavering between great pride over his work and wishing it would all just fade away. In the end:

“One does what one can, as a distinguished failure in poetry once gloomily told me over a bottle of sauterne.”

‘Mr. Starrett Wrote These’

The bulk of the book is made up of three sections, each devoted to Starrett’s productivity from the 1910s to 1941, when the book was published. This covers the period when Starrett was his most prolific, from his major detective novels and short story collections, to his poetry and his books about writers and their works.

There are also listings for promotional brochures he wrote about then-contemporary writers, little odds and ends sent to friends as holiday presents and a series of publications done by Edwin Hill.

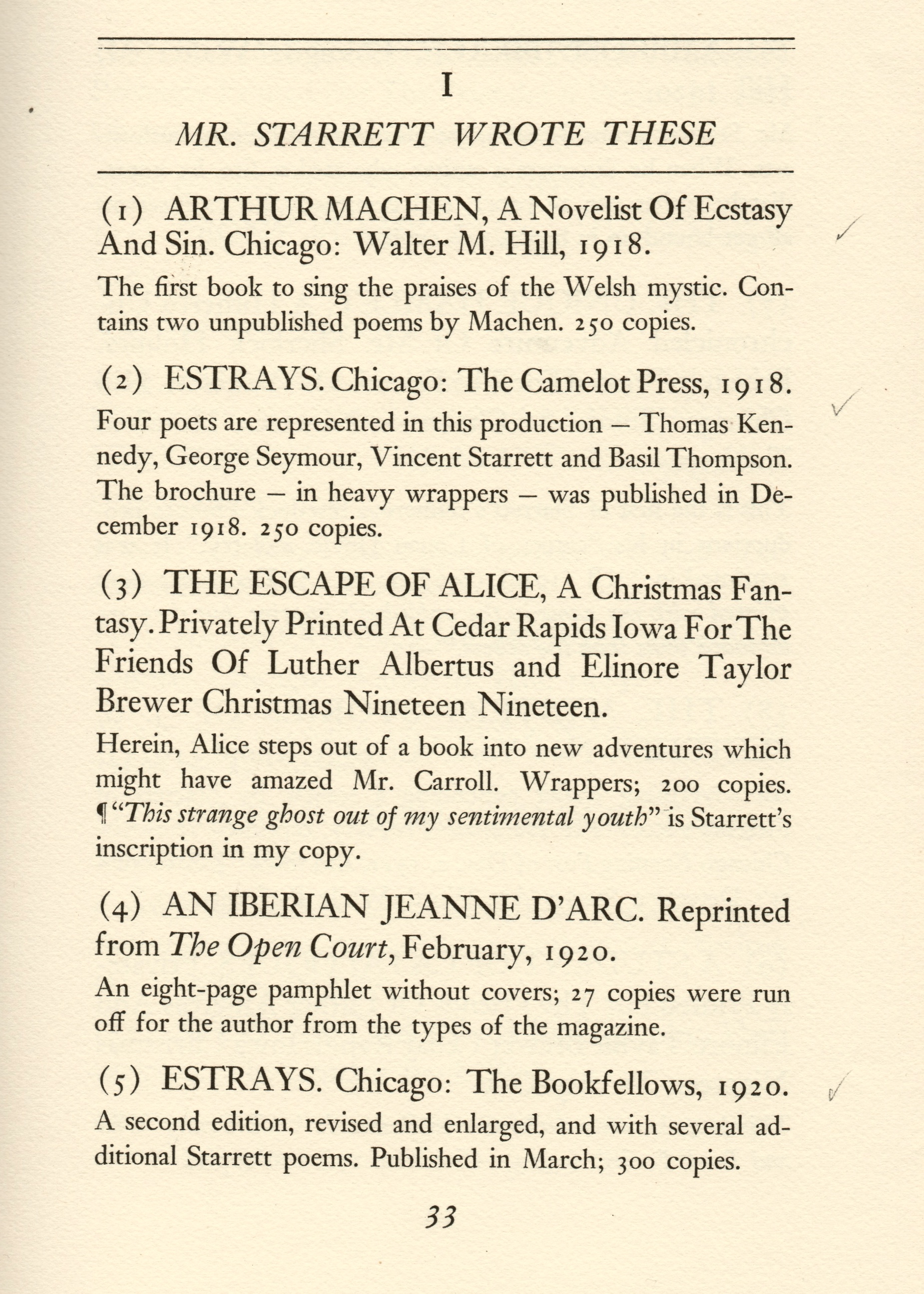

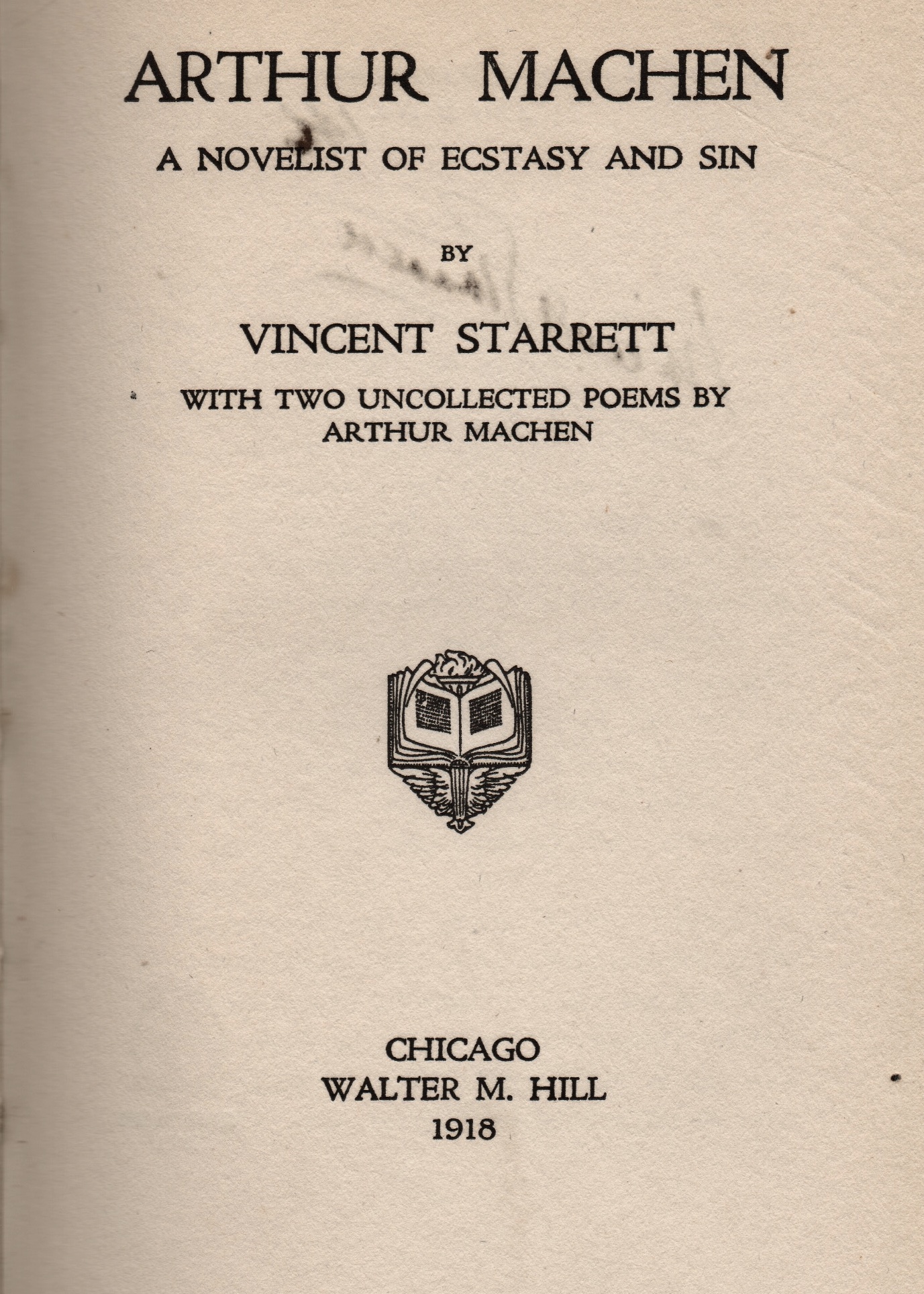

The first section of the bibliography, “Mr. Starrett Wrote These,” starts with the booklet devoted to Arthur Machen, the Gothic writer whom Starrett championed for years, and ends with Two Short Stories, a 4-page leaflet of only 25 copies that I have yet to run down.

In all, Honce counted 52 items written by Starrett. Of particular interest to Sherlockians is No. 7, “The Unique Hamlet, A Hitherto Unchronicled Adventure of Mr. Sherlock Holmes. Privately Printed for The Friends of Walter M. Hill, Chicago, Illinois at Christmas Nineteen Hundred Twenty.” Also No. 16, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1933.

To illustrate the relationship between the bibliography and my shelves, here’s the first page of the section “Mr. Starrett Wrote These,” followed by illustrations from Starrett’s booklet on Machen, and both editions of Estrays, the poetry collection that included several of his verses.

(You will see my copy of The Escape of Alice next time. It’s fun.)

In a rare case of being able to go Honce one better, I not only have the rare reprint, I also have the equally rare copy of The Open Court magazine with “An Iberian Jeanne D’Arc” in it.

So there.

And for the record, I didn’t make the tic marks in pencil shown on the page. That must have come from the previous owner.

‘Mr. Starrett Edited These’

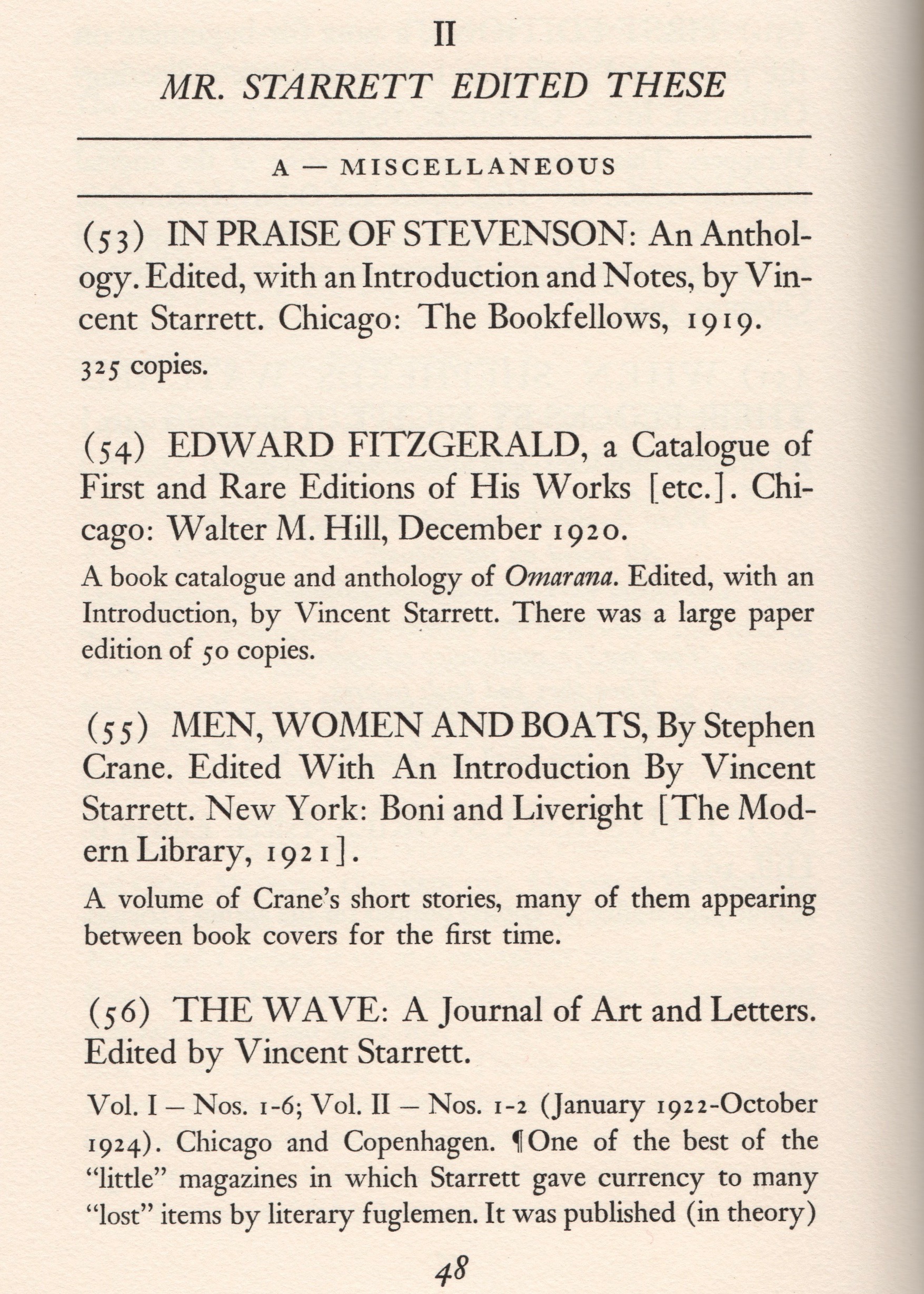

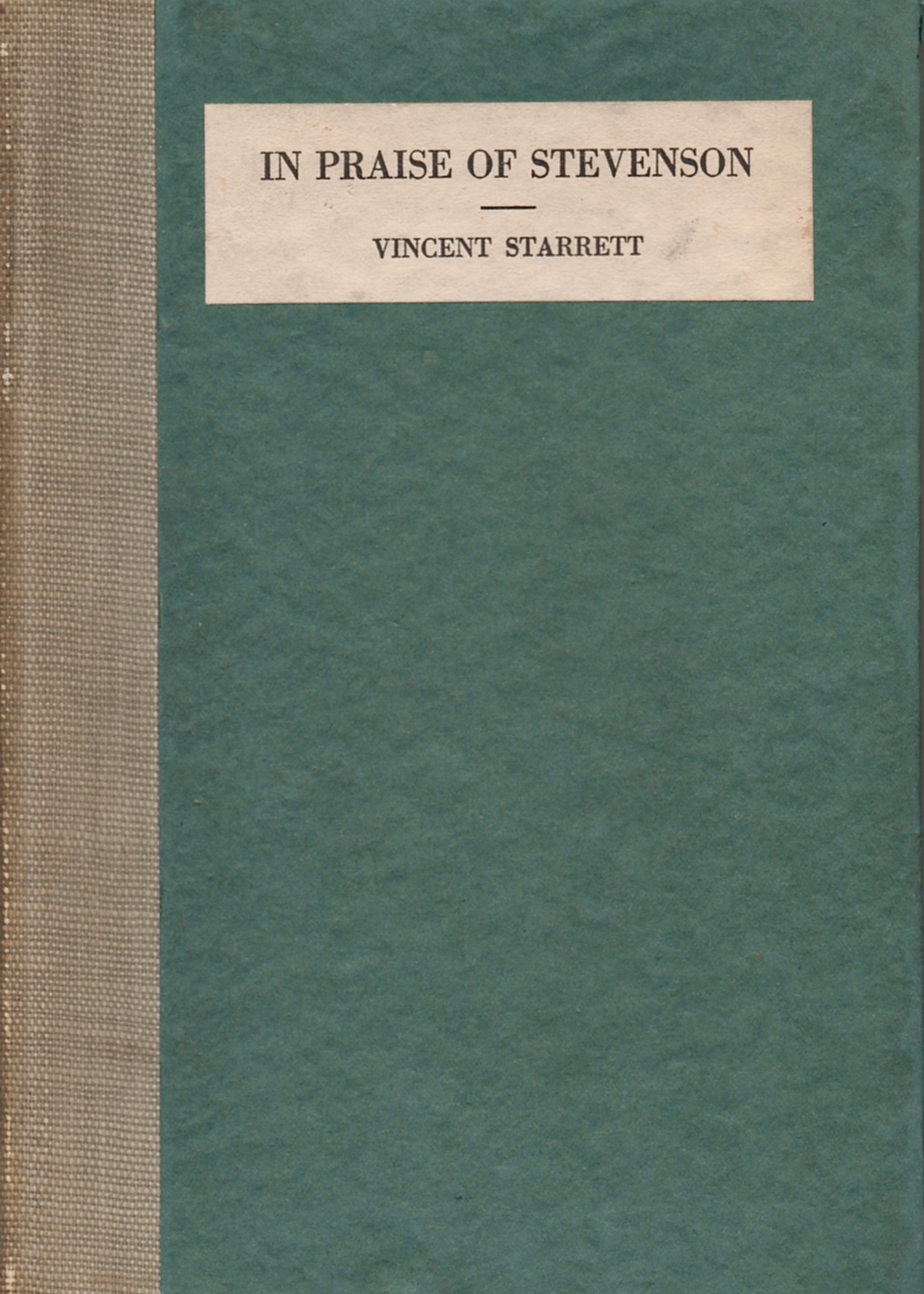

The second section, “Mr. Starrett Edited These,” (items 53-80) starts with a miscellaneous listing of items, with In Praise of Stevenson, the 1919 booklet published by the Bookfellows of Chicago.

I don’t own the Edward Fitzgerald catalogue.

Yet.

But do have copies of Men, Women and Boats, the Stephen Crane anthology that Starrett edited for Boni and Liveright, which was later The Modern Library.

I also have a couple of copies of the very rare little magazine called The Wave. I hope to have a complete run soon. The magazines are tough to find, since the paper they were printed on was not the finest quality and the issues tend to fall apart when read—a drawback for a magazine, if it’s 100 years old.

Note the background comment in the entry for The Wave. Most of these comments come from Honce, but every once in a while, Starrett offers his thoughts, as in the entry for the book Et Cetera: “In some copies my name was given by a playful printer as Charles Vincent Starrett; in most of them I was Vincent.”

Honce notes that when Starrett inscribed a copy of Et Cetera for him, the author wrote, “Regretting a great deal what I put into this book.” That self-deprecating-bordering-on-embarrassed perspective is found throughout Starrett’s comments on his early work.

Sherlockians will appreciate item No. 62, “Sherlock Holmes: A Play by William Gillette. Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1935. Edited and with an Introduction by Vincent Starrett.” Followed shortly afterwards by No. 64, “221B: Studies in Sherlock Holmes, By Various Hands. Edited by Vincent Starrett. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1940.

‘Mr. Starrett Edited These,” continued

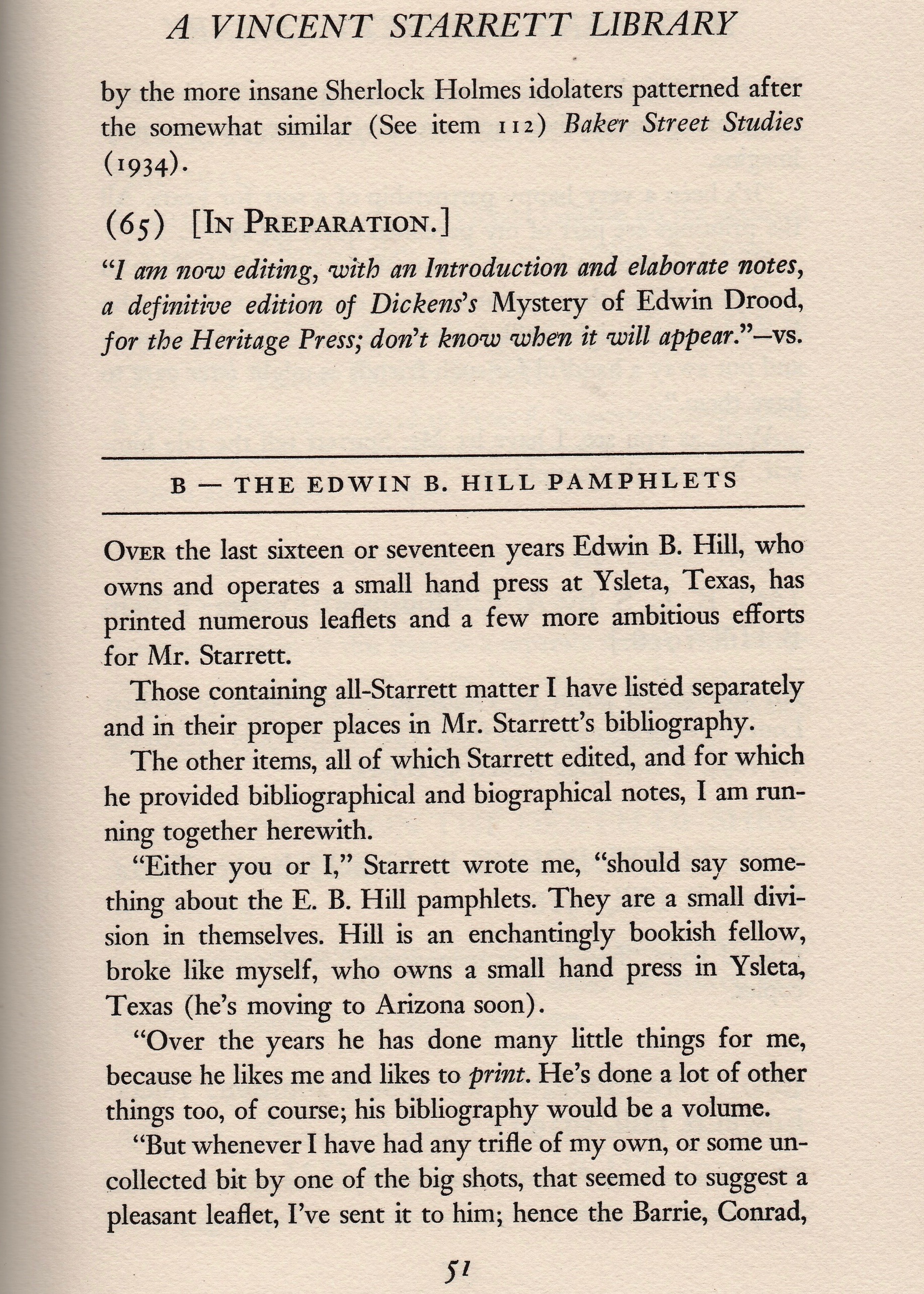

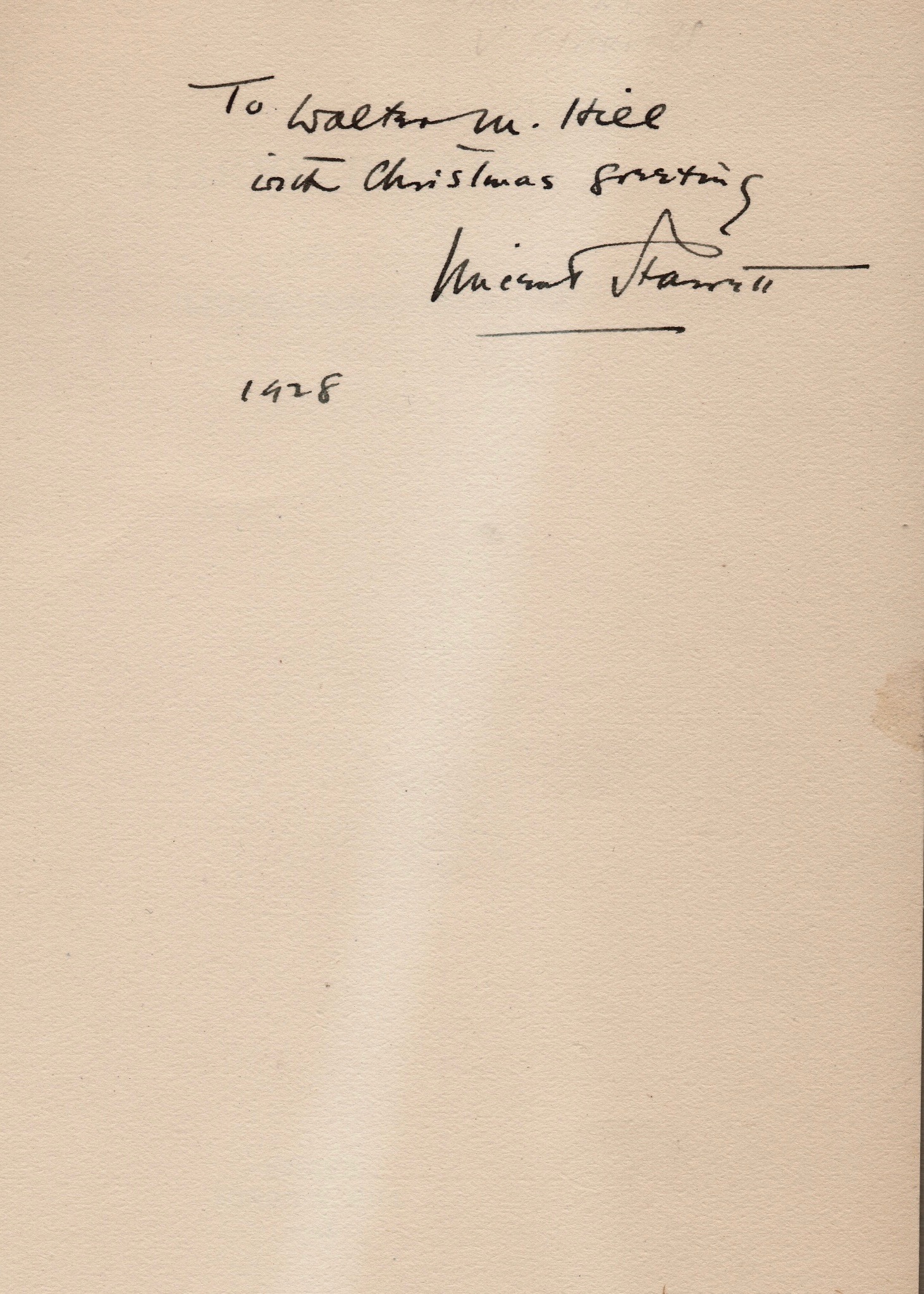

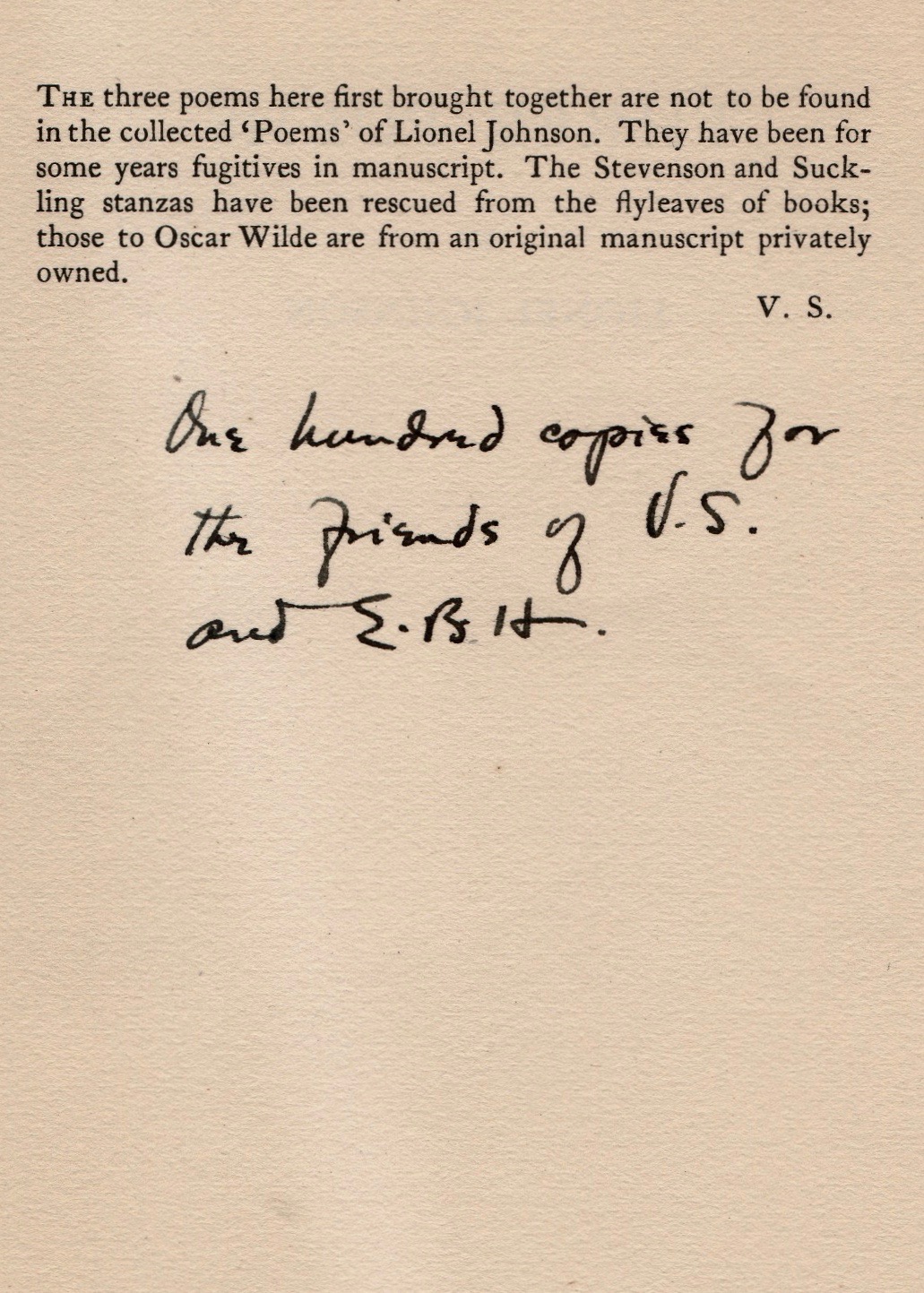

This section also contains a full listing of the Edwin B. Hill Pamphlets published up until 1941. Starrett (and sometimes others under his direction) prepared these little holiday gifts for friends.

I have nowhere near a full run of Hill publications, but I do have a few and some are fun, like the little booklet that is the second item on the list, featuring unpublished verses by Lionel Johnson, the English poet, remembered best today for introducing his cousin Lord Alfred Douglas to his friend Oscar Wilde.

History, love, inhumanity and misery ensued.

The bibliography came out one year too early to catch Starrett’s Christmas gift for 1942: Sherlockiana: Two Sonnets by Christopher Morley and Vincent Starrett, featuring the first appearance in print of the sonnet, “221B.”

‘Mr. Starrett Contributed to These’

The final bibliographic section (items 81-129) contains “First Appearances,” and “Reprints.”

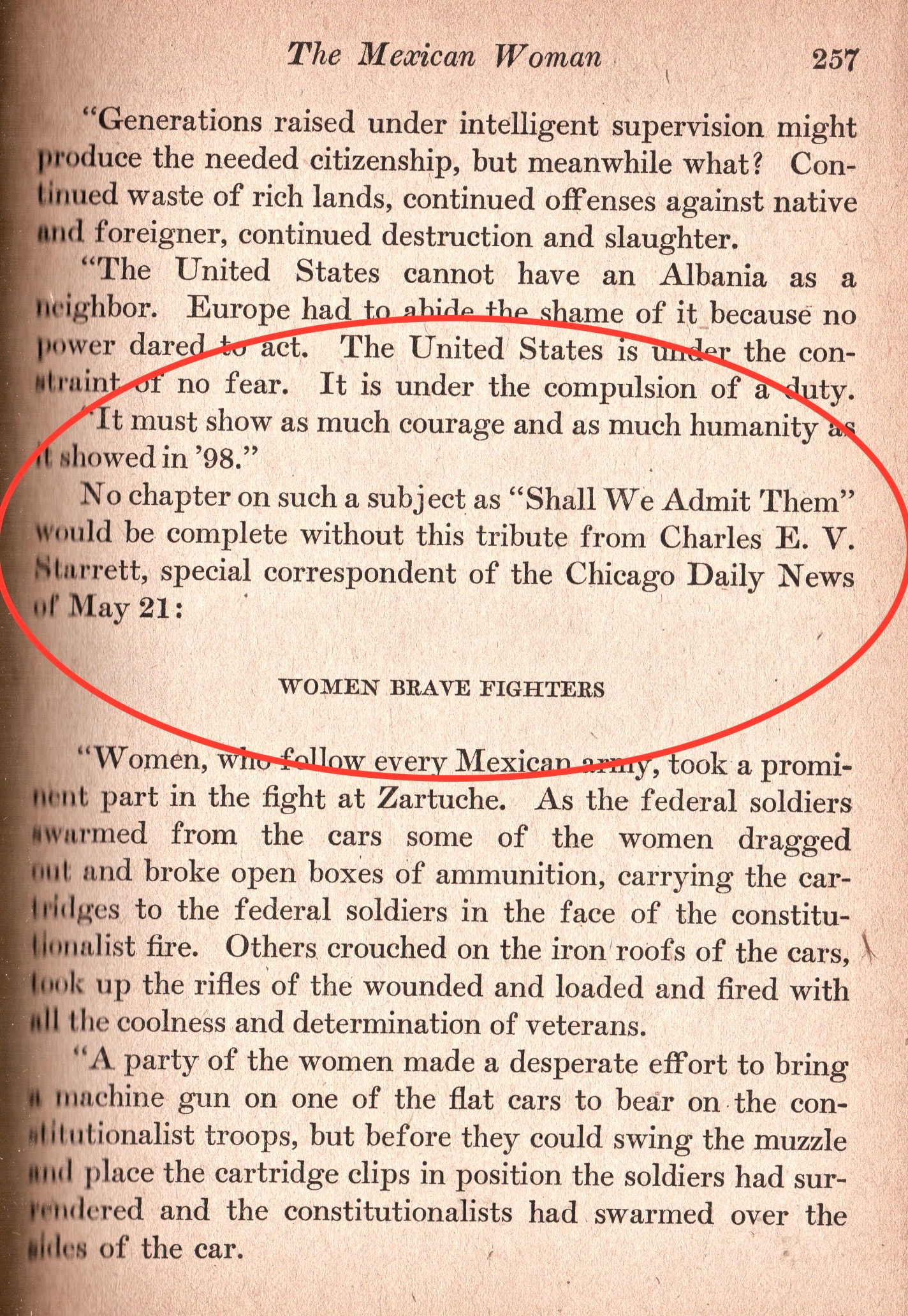

The first item in this list (No. 81) is the first time a piece written by Starrett was collected between hard covers. Thrilling Stories of Mexican Warfare, 1914, includes one of the stories Starrett wrote while covering the Mexican uprising for the Chicago Daily News.

I was stunned to be able to find a copy a few years back. It’s in only fair condition, but sure enough on page 257, there is an article by one Charles E.V. Starrett. In those early reporting days, Starrett’s work was often signed Charles Starrett, but the editor of this hastily assembled work scrambled his two middle initials. Starrett’s wounding at Xochimilco is a story that deserves deeper investigation.

No. 104 in this section includes The Adventures of Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass, which we discussed last time.

Sherlockians will recognize several early works where Starrett had either a chapter or introduction.

And item No. 122, is Honce’s bibliography now under discussion. Honce was nothing if not a completist.

Oops, I did it again. I meant for this to be the last of blog posts about the Honce/Starrett relationship, but I have a few more books to share and, if I haven’t worn out my welcome, will ask you to indulge me just one more time. After that, the whole business will be completed.

I promise.