One of "My Disciples," Part One

Charles Honce, Starrett's bibliographer

Charles Honce in a January, 1952 publicity shot.

In his book of memoirs, Born in a Bookshop, Vincent Starrett makes a passing reference to his band of “disciples.” Surely one of those disciples was Charles Honce.

A Bookish Reporter

First, a bit of background about Honce.

A newspaperman who delighted in writing bookish feature stories, Honce worked for most of his life at the Associated Press (commonly called the AP), a syndicate of news organizations that shared stories across the country. Before there was an internet, stories from the AP linked the newspapers of the United States, and eventually, the world. Charles Honce was in the middle of it all.

Born in the magical year of 1895 in little Keokuk, Iowa, Charles Ellsworth Honce’s newspaper career took him from his hometown newspaper to Des Moines, and then in 1919 to a job with the AP in Chicago. It was in the Windy City that he crossed paths with other reporters and literary folk, like Starrett.

Honce earned a reputation as a solid newspaperman, rising through the ranks of the AP between the two wars, eventually becoming an assistant general manager of news features. It was a great job. In addition to interviewing celebrities and colorful politicians, the job allowed him to roam about the nation looking for interesting feature stories, with Chicago as his base.

Late in his career, he became editor of the APME Red Book, which recorded the events at the Associated Press’s annual meeting. The example shown here has a line drawing of two of the AP’s leadership wearing deerstalker caps. I wonder where that idea came from?

He retired from the AP in 1953 and died in 1975, one year after Starrett.

The New York Times, in its obituary, noted that Honce “directed The A.P.'s coverage of such memorable events as the 1929 St. Valentine's Day massacre in Chicago, the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby in 1932 and the Morro Castle ship disaster in 1934.”

He prided himself on being a man who knew a little of everything, with a deep respect for quality news writing, which he called “literature written as the clock ticks.”

Honce was also a lifelong admirer of Sherlock Holmes. He was invested in the Baker Street Irregulars in 1944 as “The Empty House.” More about his Holmes connections in a bit.

An Unfunny Treasure

I’m not sure exactly how the Honce and Starrett first met. Chances are they ran into each other in a bookshop, or at Schlogl’s restaurant, or at some other watering hole where current and former newspapermen gathered to tell lies and laugh.

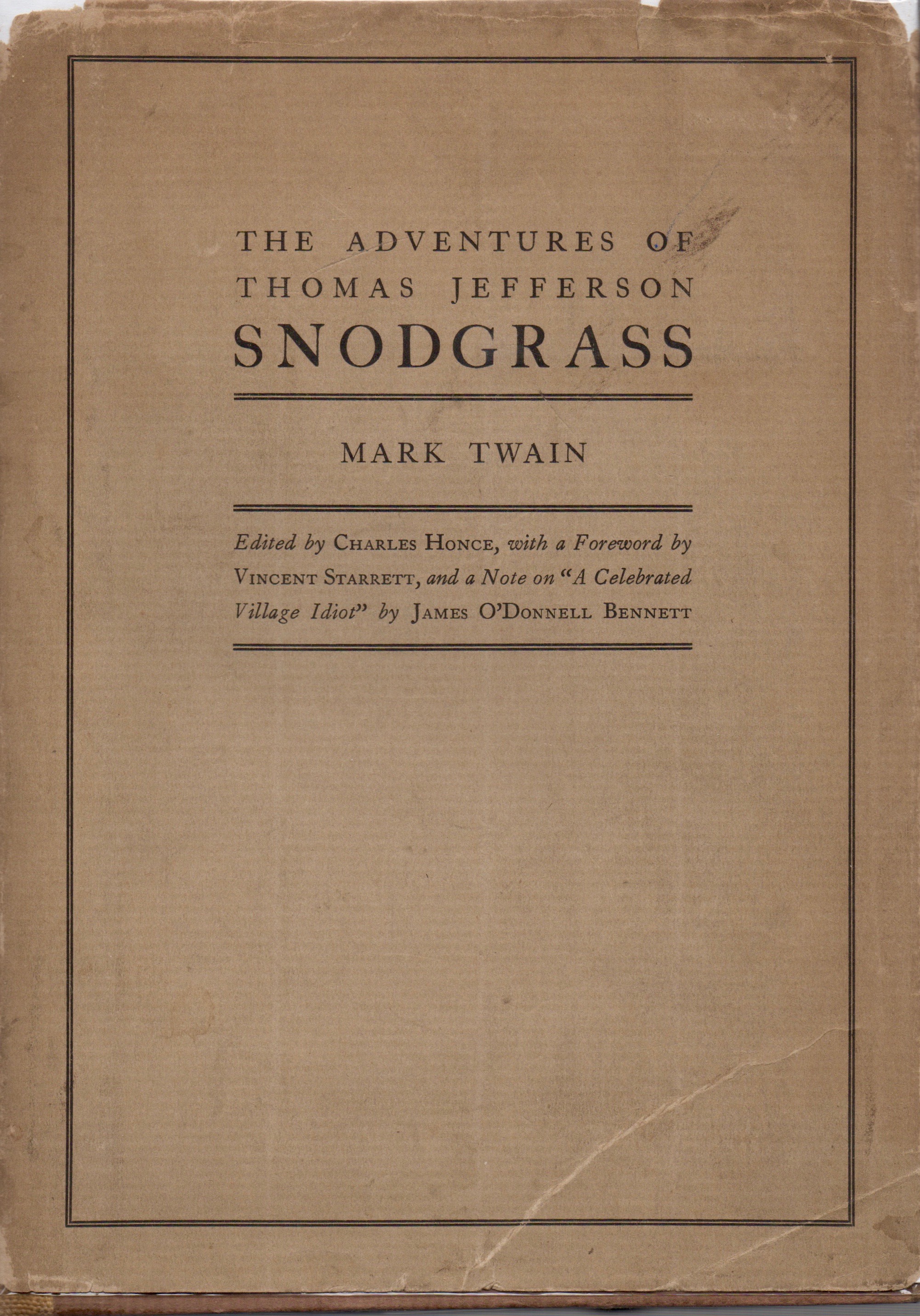

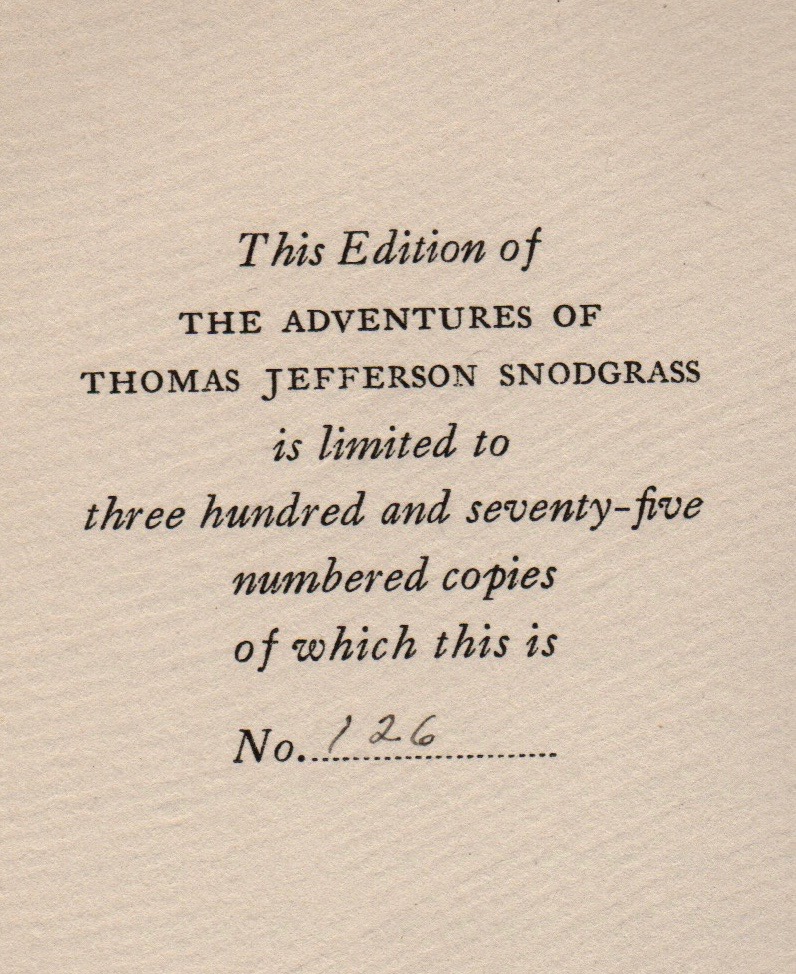

What I do know is that their first joint project was published in 1928 by Pascal Covici in Chicago. The Adventures of Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass was a true literary find: a brief series of newspaper articles written about a country bumpkin named Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass by a very young Mark Twain.

Honce discovered the articles in his hometown Keokuk newspaper, and he and Starrett planned a little book to reproduce them. Starrett wrote the foreword and Honce the introduction.

Fellow Chicago newspaperman and literary critic James O’Donnell Bennett added a note on a similar effort at country humor by another writer of the period, who might have provided a model for the young Twain. The book was handsomely produced in a limited edition of 375 and retains its quality today.

All three men were at great pains to point out the historical significance of the articles, marking as they do, some of the earliest efforts of Samuel Clemens as he transformed himself into the humorist Mark Twain. Each of the three writes respectfully of the talent Twain was honing in these country humor sketches. They left it up to Starrett to state the painful truth:

“The Snodgrass letters, it may be admitted, are not particularly funny.”

Nonetheless, the book has since become a desired item especially for Mark Twain collectors, and somewhat less especially, for those of us who collect Starrett.

Sherlock Turns 50

A portion of Charles Honce’s story about Sherlock Holmes’ 50th “birthday.” This is how the story appeared in the Democrat and Chronicle of Rochester, New York on May 9, 1937, roughly a half century after A Study in Scarlet’s appearance in Beeton’s Christmas Annual.

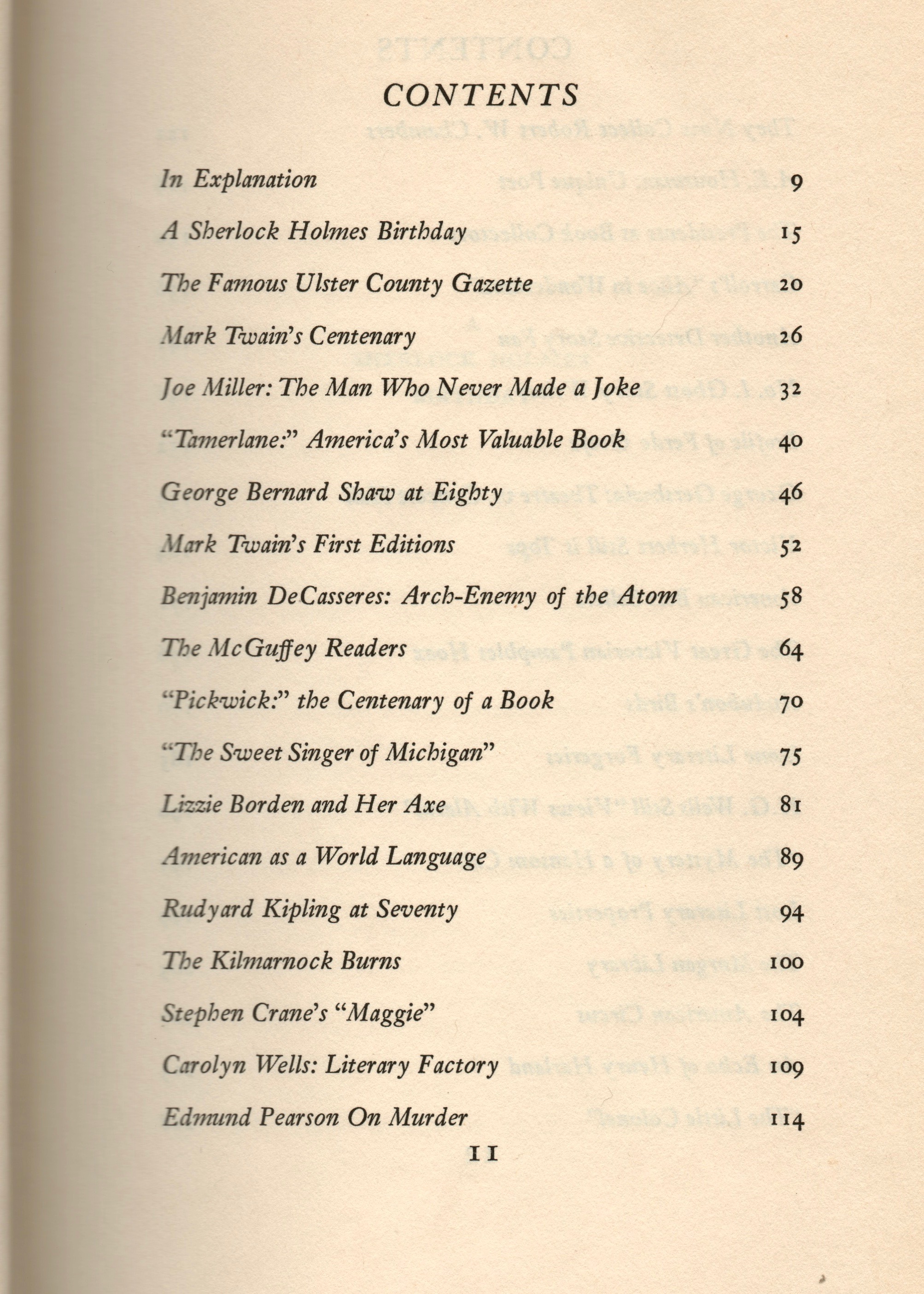

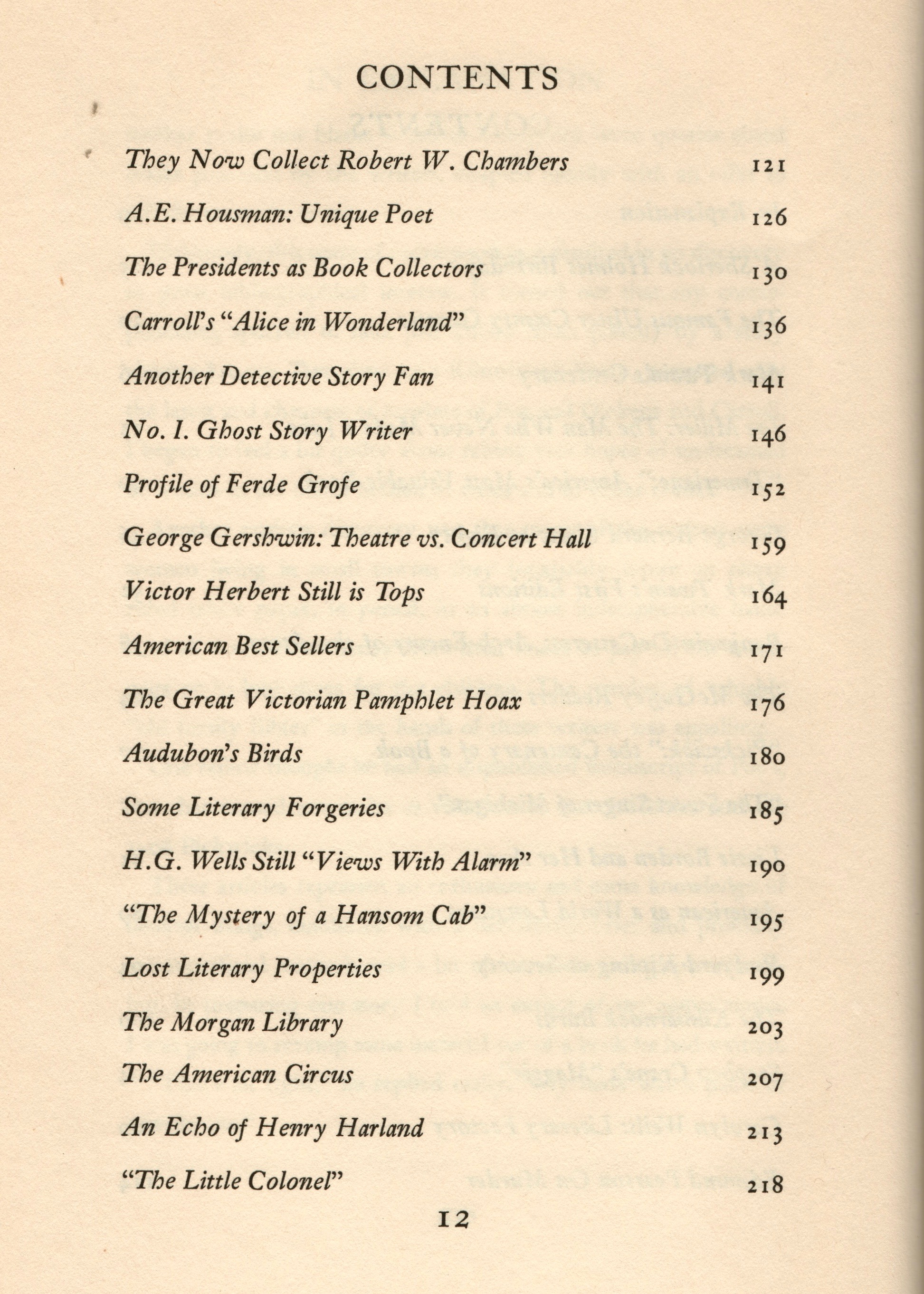

Let’s skip nearly 10 years to 1937, when the world was celebrating the 50th anniversary of A Study in Scarlet. Honce had by this time established that news stories on the anniversary of famous bookish events could become popular features, “to compete for space in newspaper columns with tidings of murder and alarums of war.”

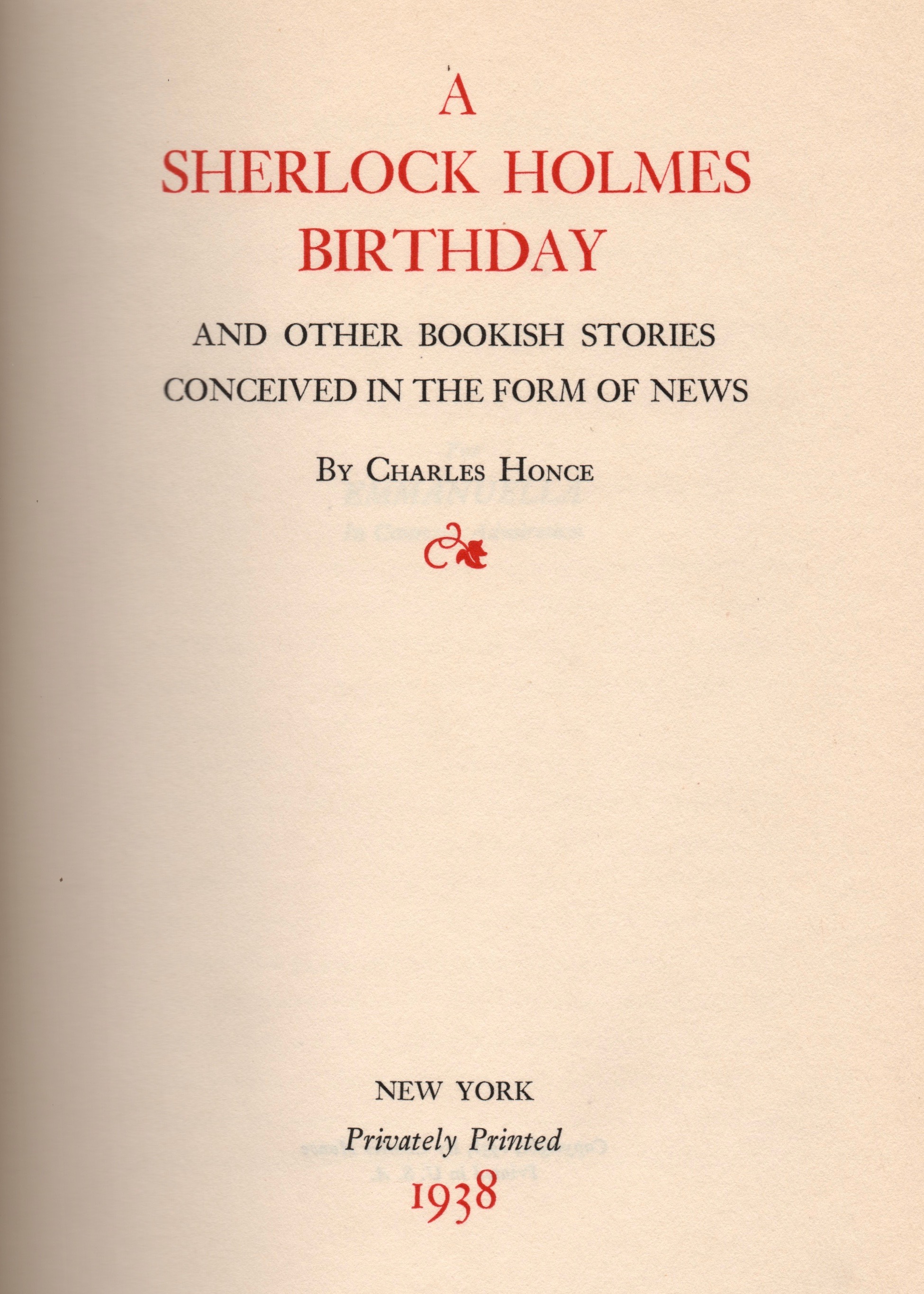

His first success came with the 100th anniversary of the Pickwick Papers in March, 1936. That went so well that he looked for other opportunities to feature books “from a ‘news’ standpoint rather than from a critical angle.” (These quotes by Honce come from his preface to A Sherlock Holmes Birthday, and other bookish stories conceived in the form of news, privately printed in New York in 1938. More on the book in a moment.)

Having an interest in Holmes himself, Honce wrote a detailed story that went out on the wires on April 17, 1937.

After a quick summary of Holmes’ creation, Honce quickly shifts to the highly influential work of Frederic Dorr Steele, who was at the time living

“on the top floor of a Greenwich Village Apartment. He probably will draw no more Sherlock Holmes pictures, but he is so steeped in the Sherlock Holmes tradition that he serves as a very definite and personal link with the man who has been called the greatest fictional creation of the last half century.”

Just as Arthur Conan Doyle was frustrated that his other work was overwhelmed by Holmes’ popularity, so Steele has lived with having much of his work overshadowed by his drawings of the master detective, reports Honce. People keep asking Steele if there are other originals of his Holmes work, but the only item left to him at this point is a small silhouette of Holmes looking through his magnifying glass at a miniature of the illustrator. (Honce would later own the image.)

The story goes on to describe how Vincent Starrett portrayed Holmes’ birth in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Borrowing liberally from Starrett’s book, Honce describes the early years of the Holmes canon, noting that American illustrators struggled to bring the detective to life until Steele was given the job, using William Gillette as a model. Says Steele:

“Everybody agreed that Mr. Gillette was the ideal Sherlock Holmes, and it was inevitable that I should copy him. So I made my models look like him, and even in two or three instances used photographs of him in my drawings.”

The story was popular and ran in Sunday newspapers around the nation, often with the illustration of Holmes observing Steele, as you see here.

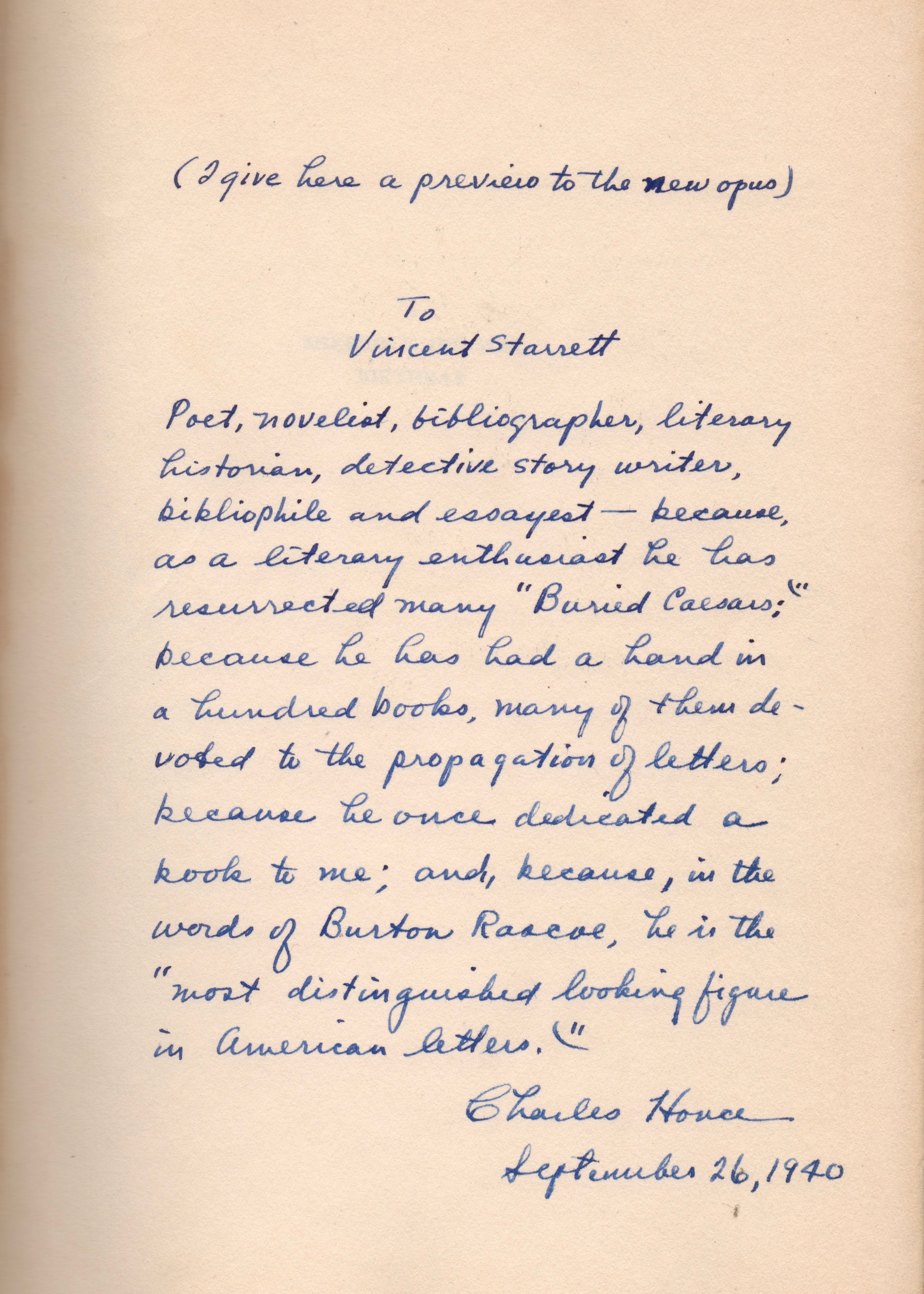

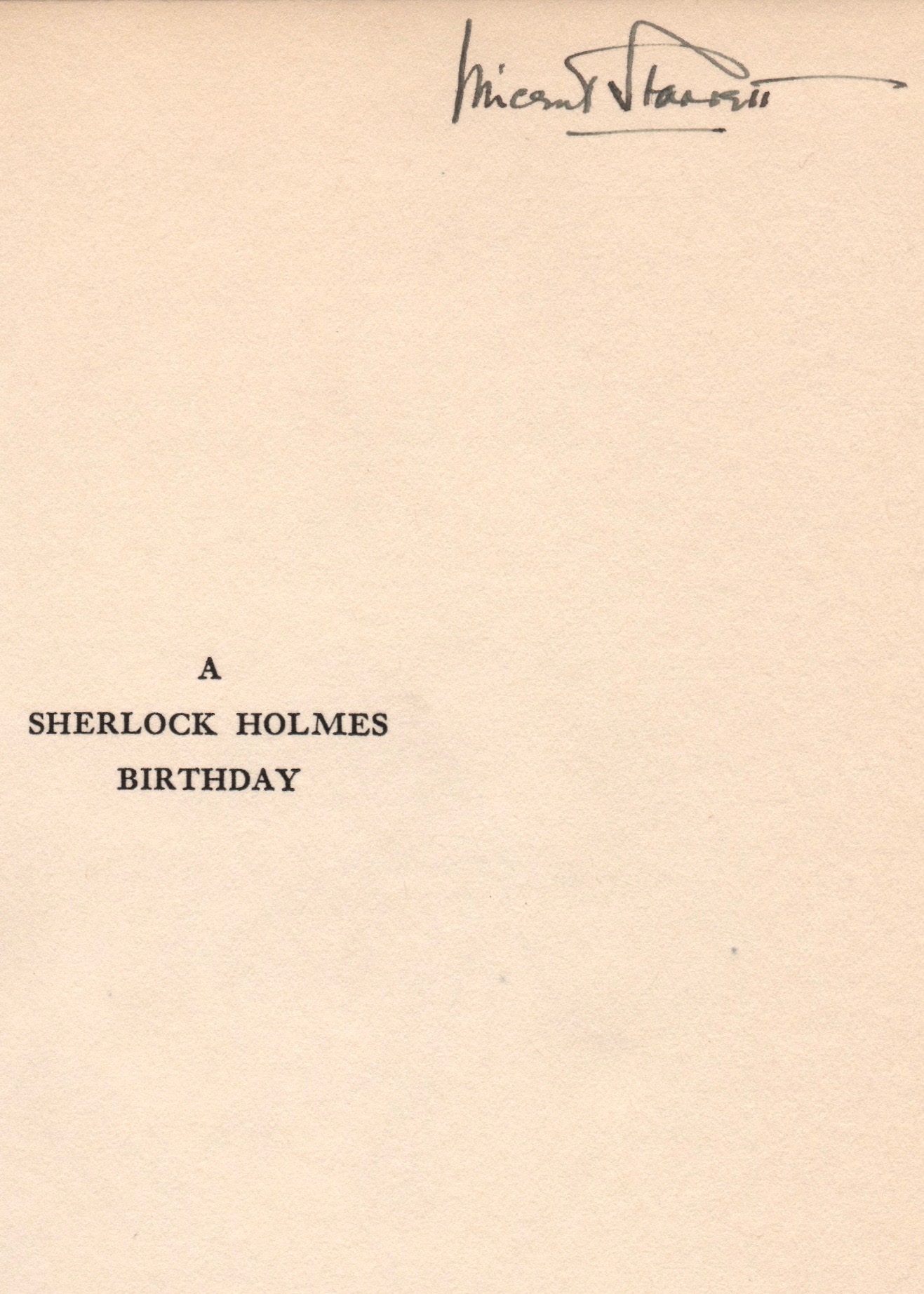

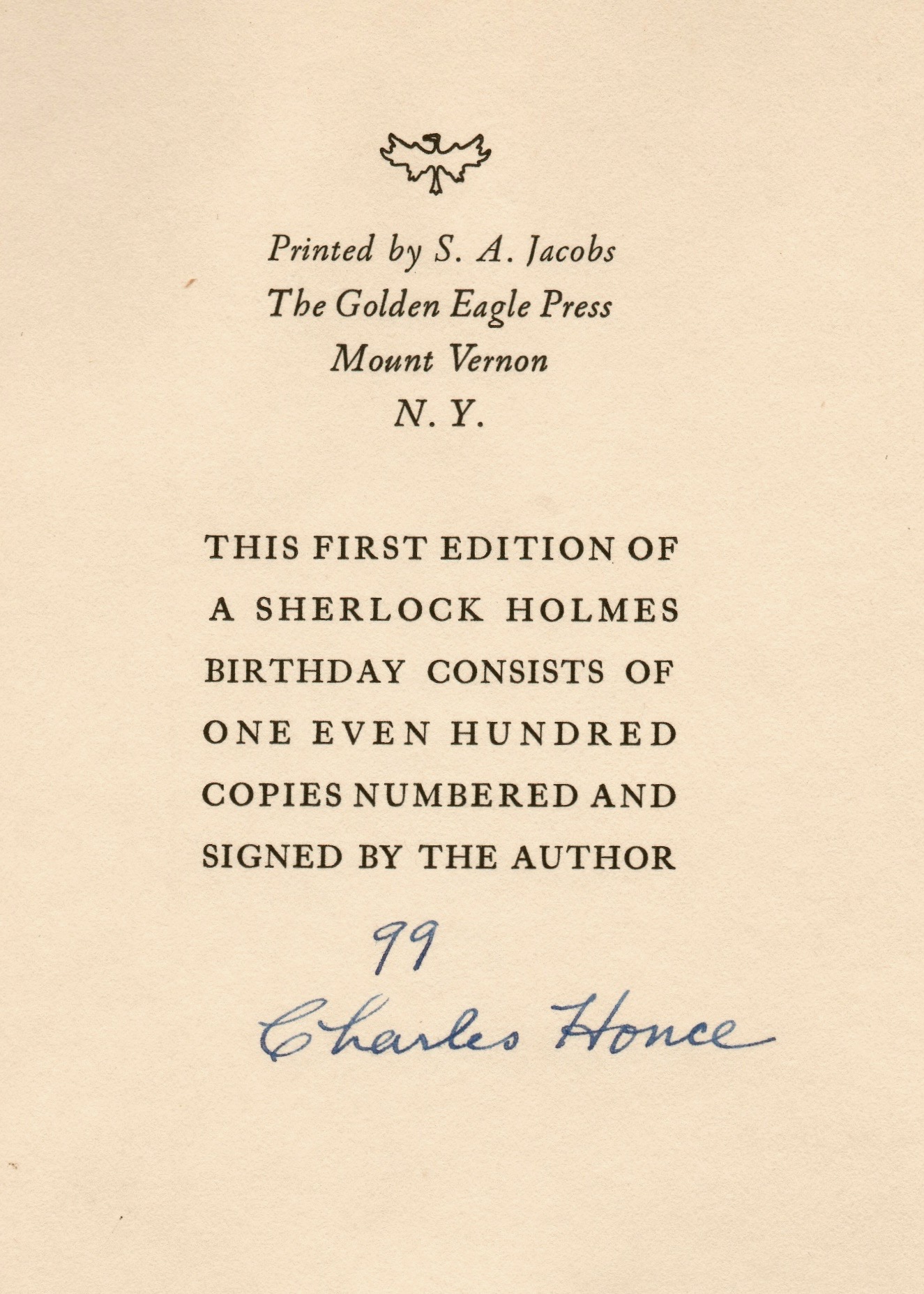

These bookish features were so popular, in fact, that in 1938, Honce bundled them up and published them in a highly limited edition of 100. No. 99 was inscribed by Honce to Starrett and is now on my shelf, as you shall see.

Collecting the clips: A Sherlock Holmes Birthday and other bookish stories conceived in the form of news

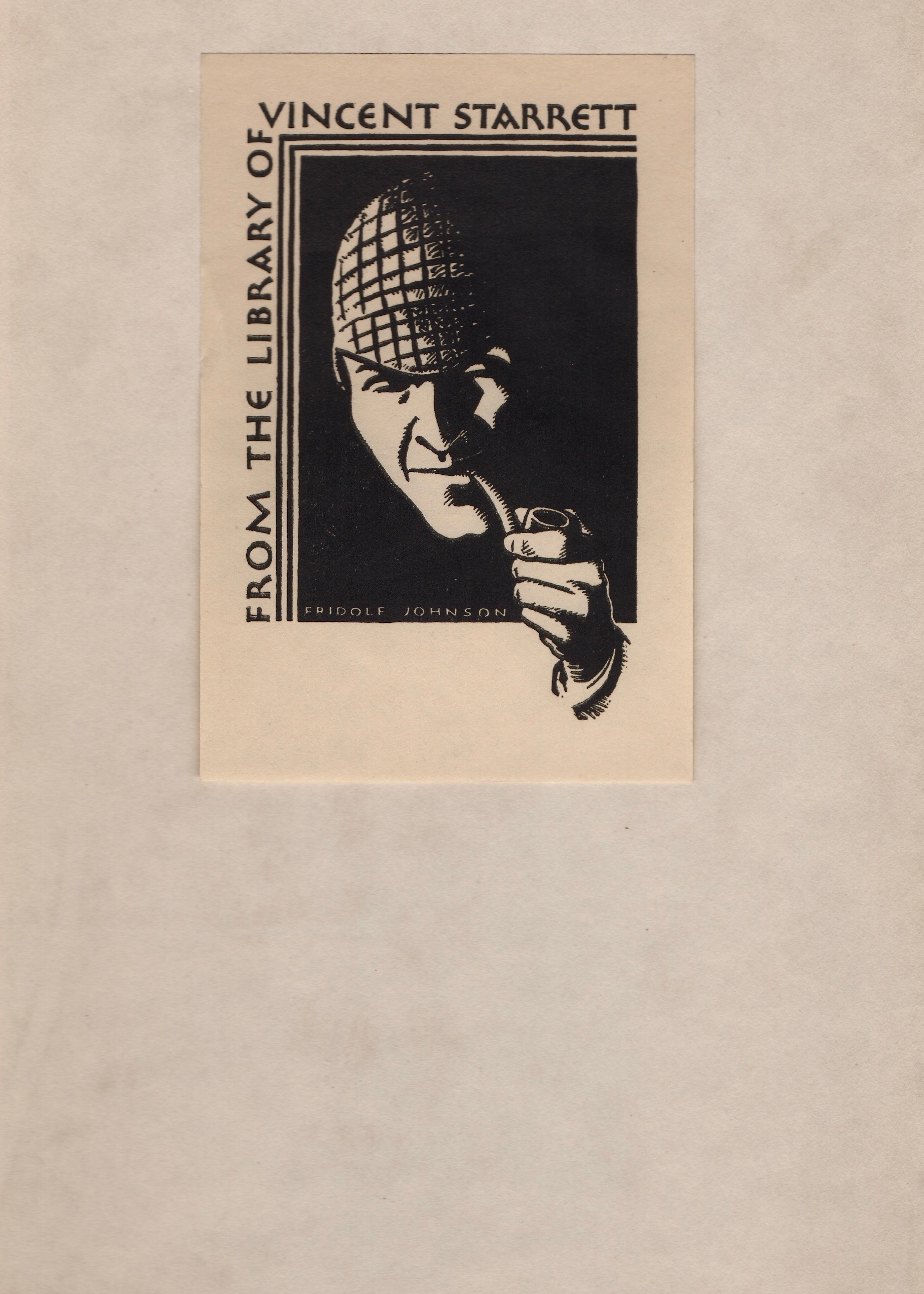

The red cloth covers are undecorated, and the gold stamping on the spine has faded with sun, but flip it open and one is immediately greeted like an old friend. There on the inside front cover, is Sherlock Holmes in Fridolf Johnson’s handsome bookplate. While neither the bookplate nor the signature would assure that this was once in Starrett’s collection, the inscription from Honce removes any doubt. Here’s what he wrote:

(I give here a preview to the new opus.)

To

Vincent StarrettPoet, novelist, bibliographer, literary historian, detective story writer, bibliophile and essayist — because, as a literary enthusiast he has resurrected many “Buried Caesars;” because he has had a hand in a hundred books, many of them devoted to the propagation of letters; because he once dedicated a book to me; and because in the words of Burton Rascoe, he is the “most distinguished looking figure in American letters.”

Charles Honce

September 26, 1940

Notes on the inscription:

“a preview to the new opus”. Honce’s bibliography was about to be published, hence this collection of Honce’s work is a preview of his work on Starrett.

“he has resurrected many Buried Caesars.” One of Starrett’s first book of essays was titled Buried Caesars. In it, he reminds readers about the talents of forgotten or neglected authors.

“had a hand in a hundred books.” Just how many books Starrett wrote, edited or was otherwise associated with is a subject of some debate, and while Honce tried to quantify Starrett’s output, he actually made the estimate worse. More about that next time.

“he once dedicated a book to me.” Midnight and Percy Jones, a mystery featuring Starrett stand-in Riley Blackwood, was published in 1938 and the dedication reads: “To Charles Honce/With gratitude for his grand idea.” Exactly which idea is represented in the book remains a mystery.

It is a beautiful inscription, detailed enough to get a real sense of the admiration and respect they shared. It is also a tribute to the kinship that can be built between two people who both admire Sherlock Holmes. In this inscription, their kinship lives though the two are no longer with us.

Stay tuned

I had hoped to write just one post about the Honce/Starrett friendship, but as you can see, this one’s running long and I have a lot of territory to cover. So look for part II, coming soon to a bibliographical blog near you.