'Part of a slim volume"

Chapter 7: ‘Let us be done with all this solemn prattle’

"A definitive collection"

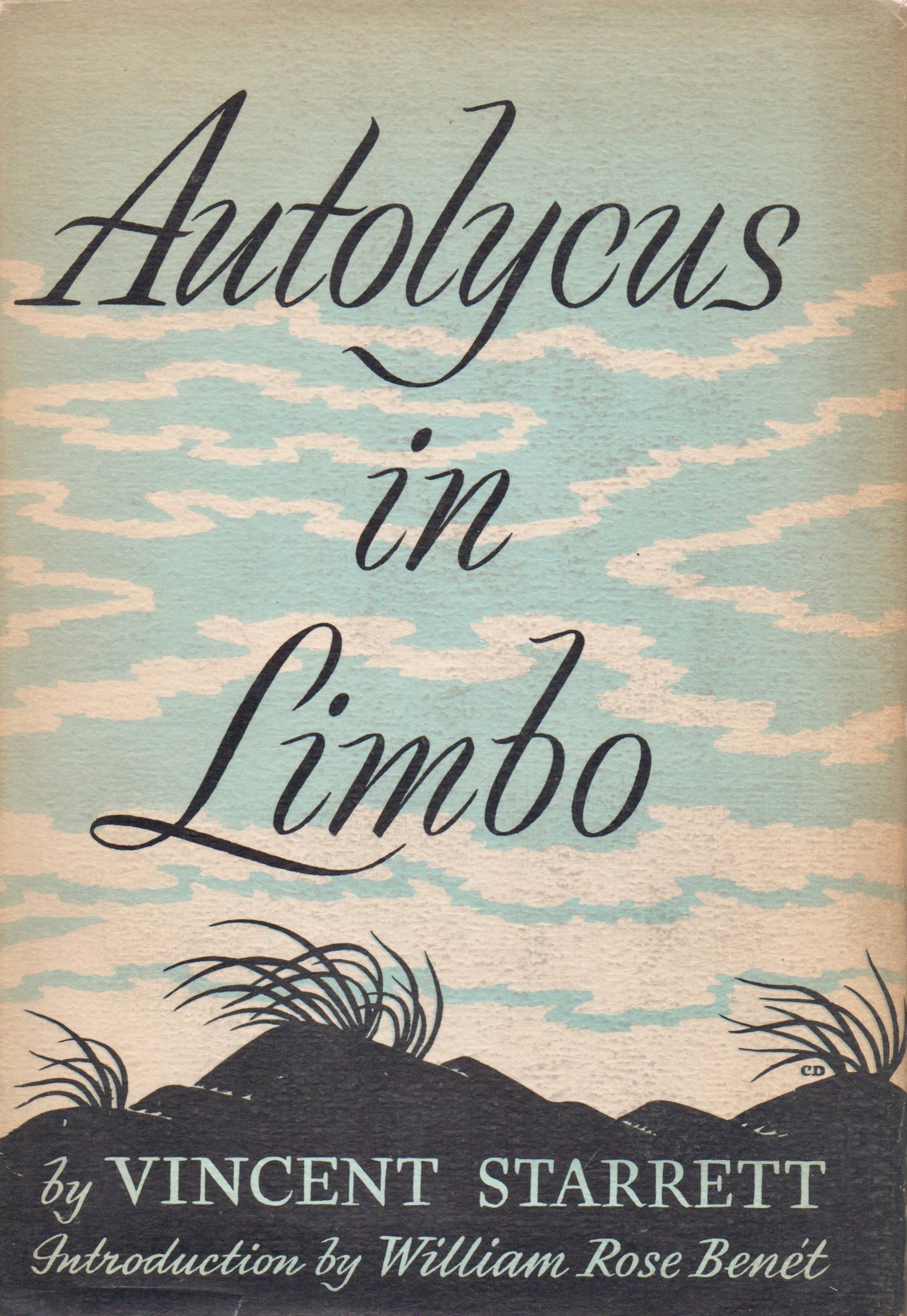

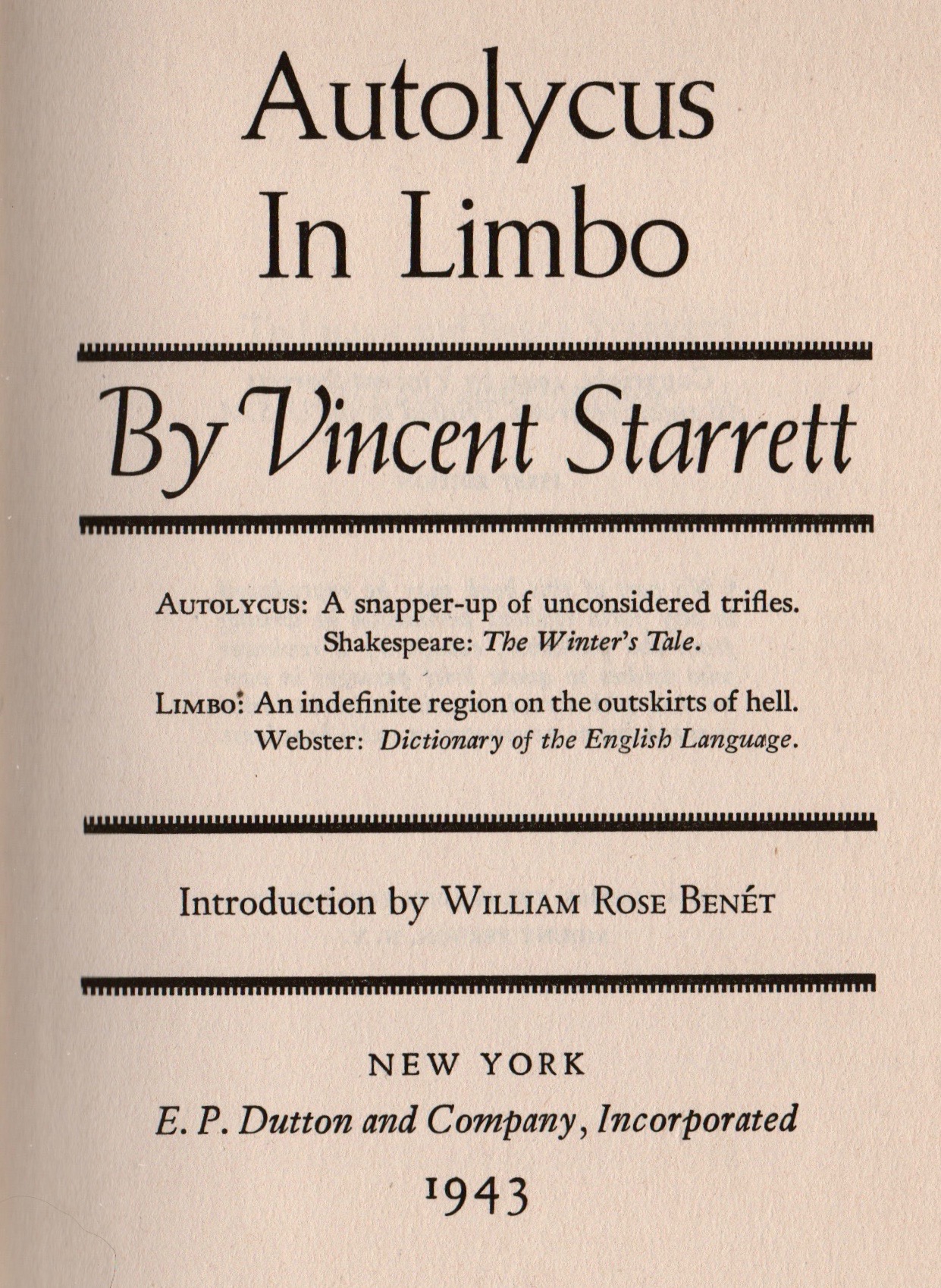

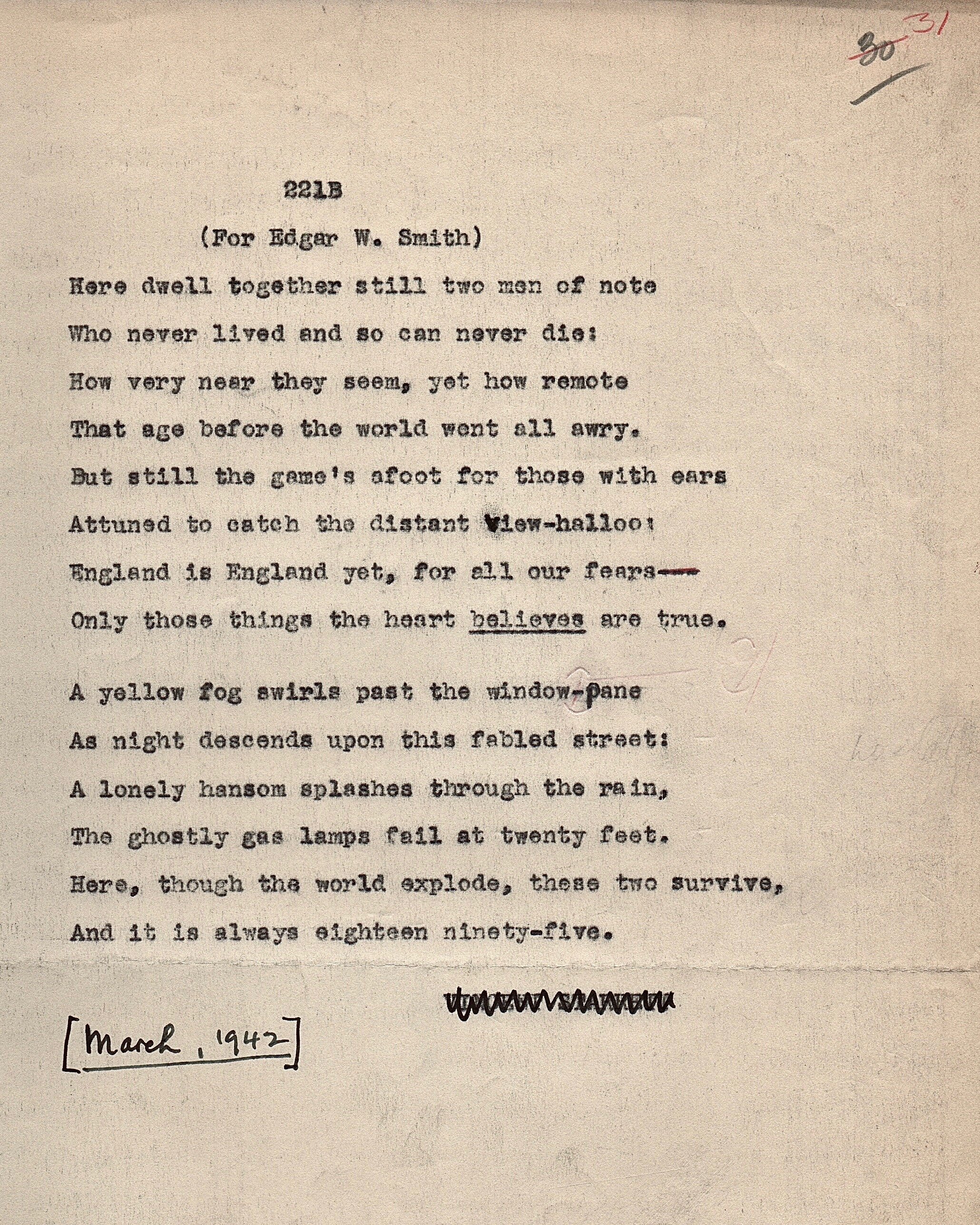

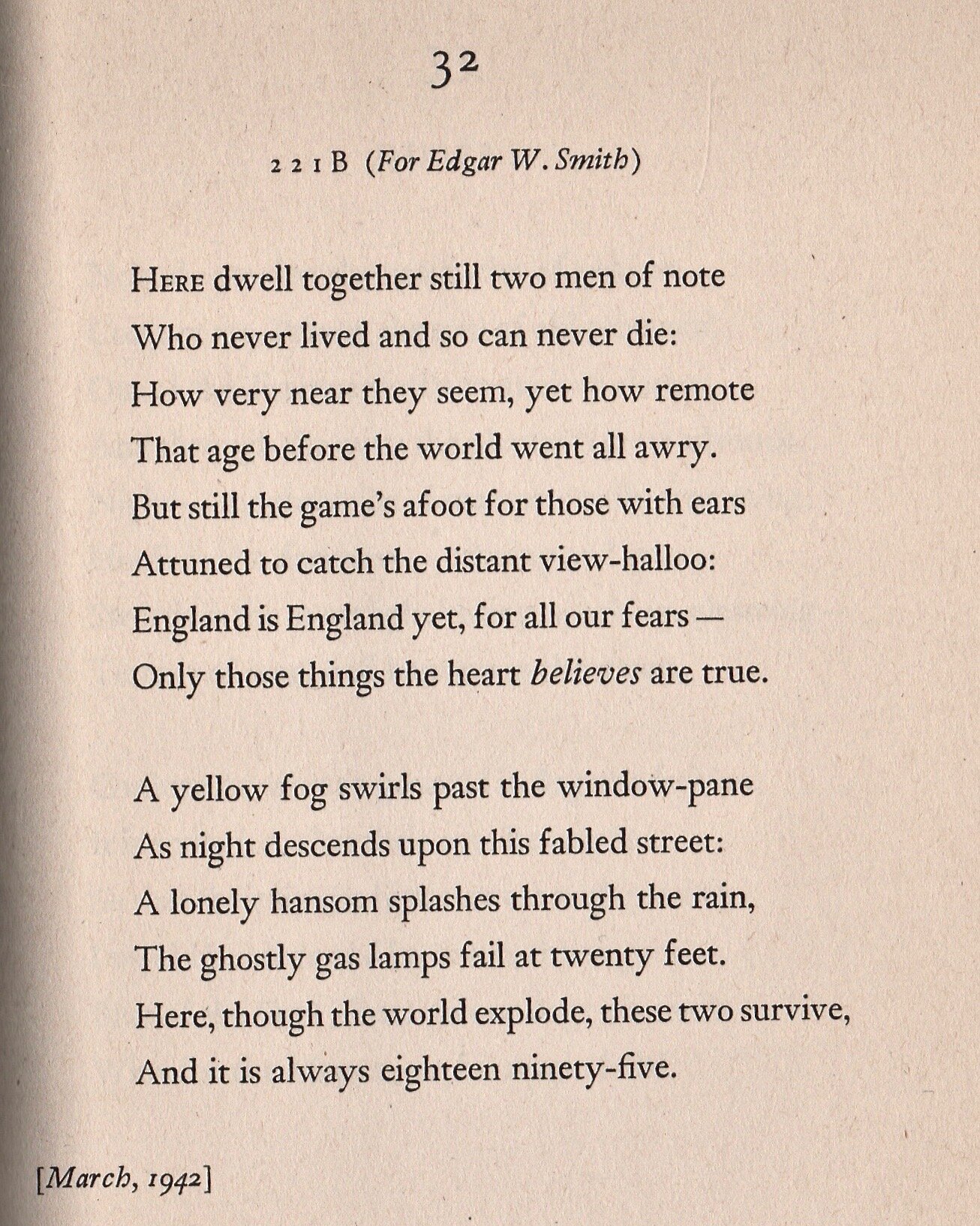

When sending “221B” to Edgar W. Smith, Starrett said he hoped it would soon “be part of a slim volume,” That slim volume of poetry was published by E.P. Dutton on August 8, 1943, and entitled Autolycus in Limbo. Limited to 1,500 copies, it is easy to find these days on the used and rare book market.

Starrett wrote in his memoirs that when Charles Honce put together a bibliography of his work, Honce encouraged him to find a publisher for his favorite poetry. Although the verse had found outlets in newspapers, magazines and little booklets, the last book of his poetry, Flame and Dust, had been published in 1924.

“For some time I had been hoping to bring out a definitive collection, and this was accomplished in 1943 with the publication by Dutton of Autolycus in Limbo, for which William Rose Benét wrote the introduction."

(From Born in a Bookshop by Vincent Starrett, University of Oklahoma Press, 1965.)

The book’s unusual title comes from two sources: A comic thief in Shakespeare’s play “The Winter’s Tale,” boasts that he is named after the Greek figure Autolycus and, like him, is "a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles". The word “trifles” no doubt caught Starrett’s ear, attuned as it was to a word that was a favorite of the Baker Street detective.

Limbo, of course, refers to a portion of Hell. Why Starrett picked this allusion to Hades is unclear. I’m tempted to think the fire bombing of so many cities during the war led him to think of the fires of Hell. Regardless of the spark, this was the kind of literary reference Starrett loved to scatter among his poetry.

Of all the writing that Starrett had done throughout his life—newspaper reporting, bibliographies, short stories, mystery and detective novels—his first love was poetry. Now he felt the time was right.

Autolycus in Limbo was designed to be Starrett's poetic magnum opus, a "best of" sonnet collection that would once and for all put this verse before the public between hard covers.

‘Let us be done with all this solemn prattle’

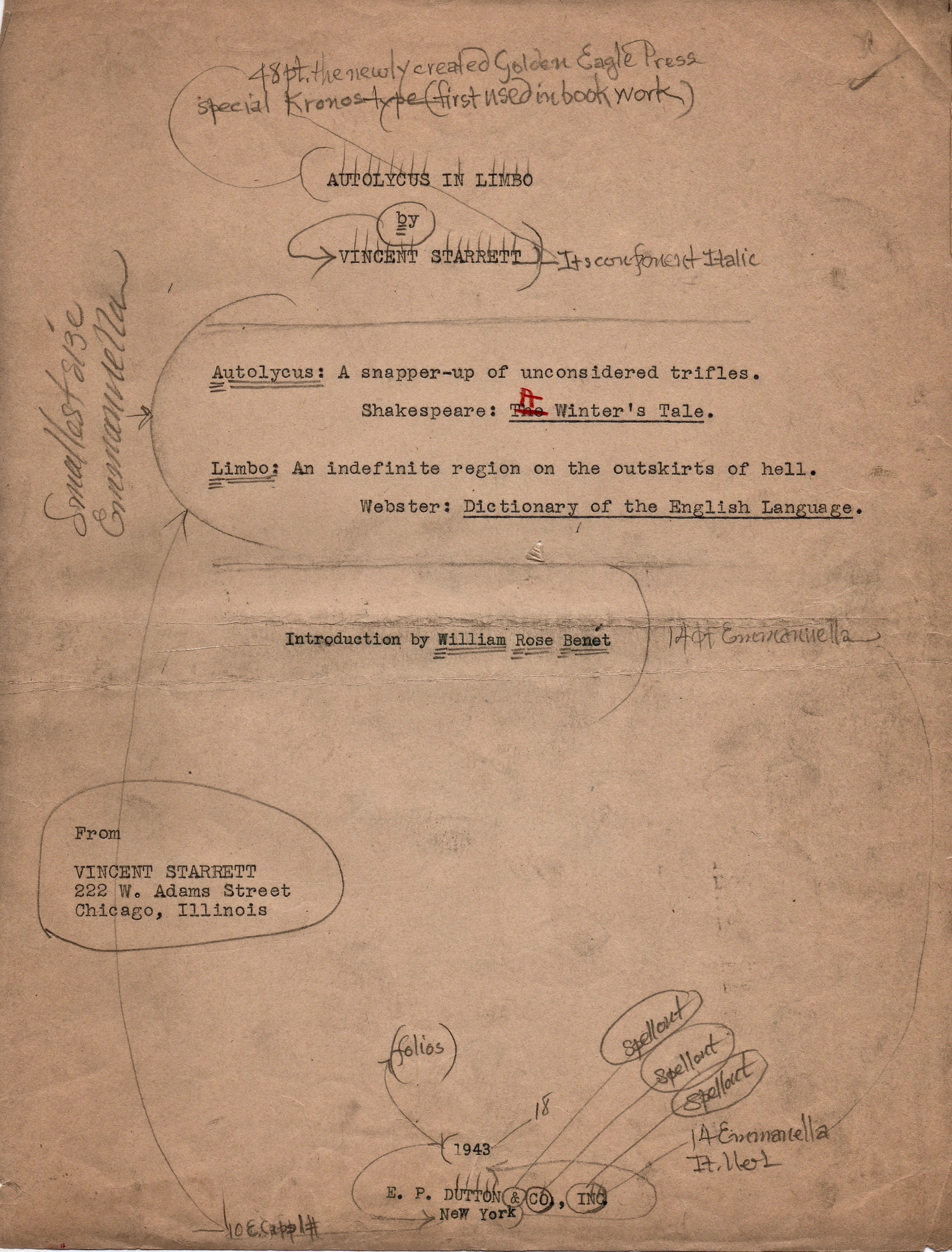

A few years ago I had the great good fortune to acquire the manuscript for Autolycus in Limbo and have it here as I write. The pages of the manuscript supply some of the illustrations for this chapter.

“221B” is one of the book's 85 poems, many of which have literary allusions.

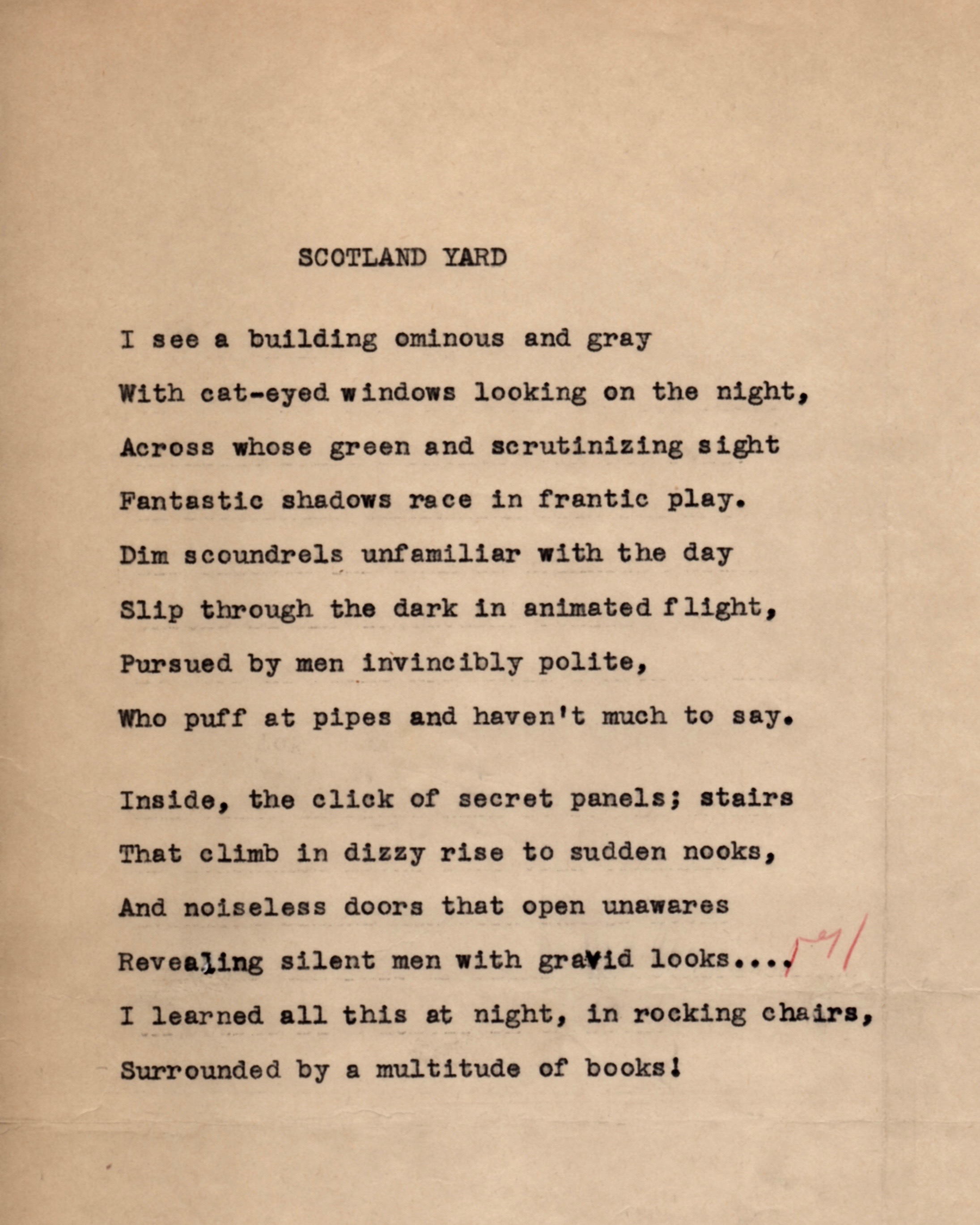

There are paeans to D’Artagnan, Dumas, Dupin, Falstaff, Pickwick and Don Quixote. There are also two tributes to the detective story, the first entitled “Scotland Yard,” is a love story to reading mysteries and ends with a vision of Starrett in his preferred habitat:

"I learned all this at night, in rocking chairs,

Surrounded by a multitude of books!"

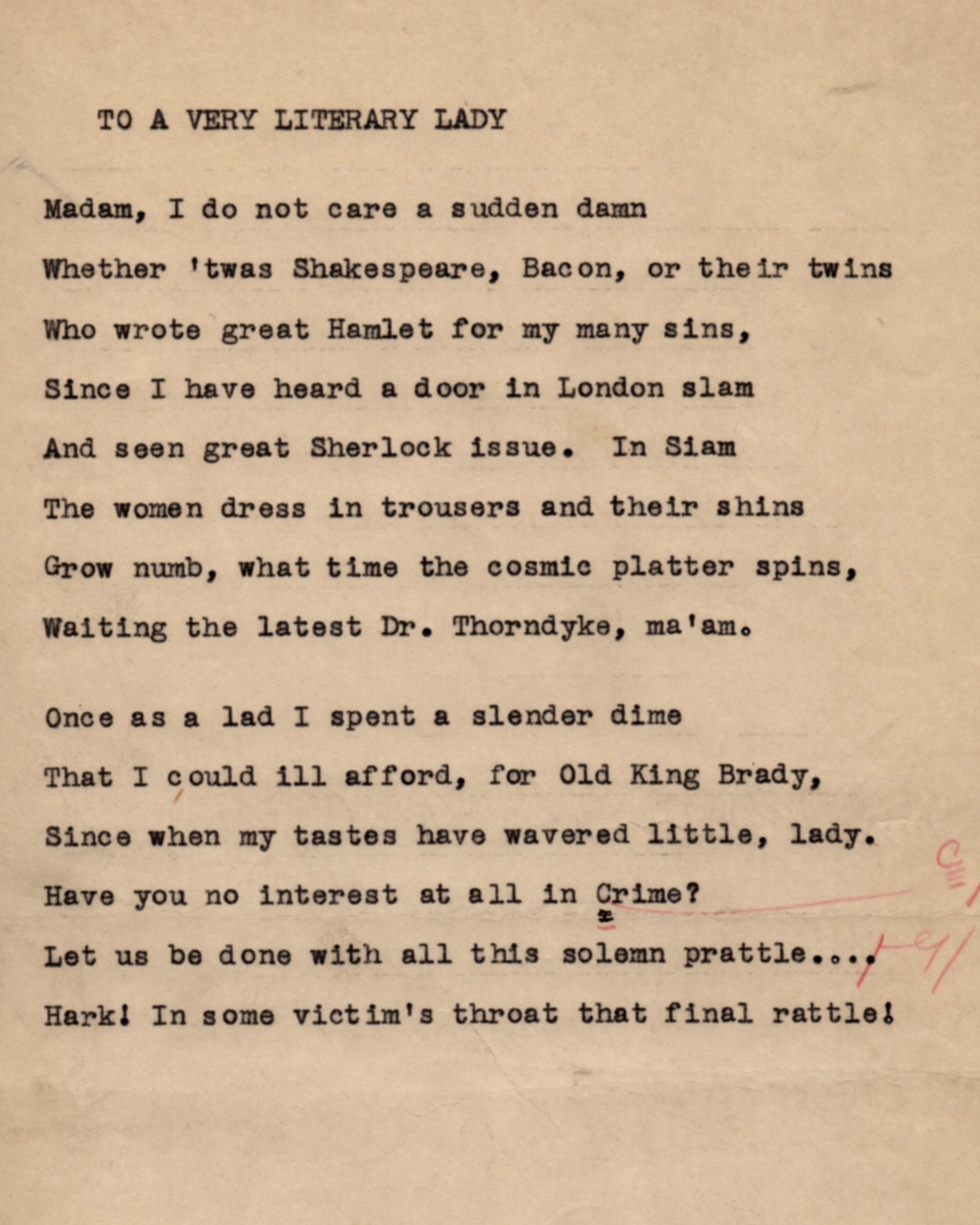

The second is a favorite of mine, “To a Very Literary Lady.” I believe it was the only poem Starrett had published in The New Yorker, and was a rebuke to a snooty woman who didn’t read detective stories. Holmes makes a quick appearance:

"Madam, I do not care a sudden damn

Whether 'twas Shakespeare, Bacon, or their twins

Who wrote great Hamlet for my many sins,

Since I have heard a door in London slam

And seen great Sherlock issue…"

Best of all is this final sentiment:

Let us be done with all this solemn prattle . . .

Hark! In some victim’s throat that final rattle!

Here is the manuscript version of Starrett’ poem, fresh from his typewriter, and how it appeared in the printed volume.

‘Competent, diverting, entertaining’

LIke many of Starrett’s books, Autolycus in Limbo was hardly a best-sellter. Reaction among the critics was kind, but hardly enthusiastic. “Competent, diverting, entertaining,” said the reviewer for the Oakland (Calif.) Tribune.

“Mr. Starrett evidently enjoys himself hugely and the reader will find himself chuckling in sympathetic appreciation with the poet,” noted the critic for the El Paso (Texas) Herald-Post.

A notice in the Philadelphia Inquirer agrees that humor is Starrett’s strongest quality and this “sheaf of lyrics is distinguished principally for their refreshing humor.”

Writing in the Louisville Courier-Journal, Mary E. Burton says she enjoys the easy readability of the stories, but laments that “Starrett seems to have no style of his own.”

Addie May Swan in the Davenport Democrat captures the sense of Starrett’s poetry best:

“Vincent Starrett may be described as having one foot upon a cloud, and the other on terra firma. He is fanciful and realistic; he is bookish and savors life and its contradictions to the full; he is a creator of captivating phrases, but if he takes his readers along with him to a poetic height, it is best to be prepared for a sudden fall to earth.”

A clip of Richard Hart’s review from The Evening Sun of Baltimore on July 17, 1943.

I’ve tracked down about two dozen contemporary reviews of the book. While critics plucked their favorites to quote in full or in part, only one that I’ve found mentions “221B.” Richard Hart, writing in the The (Baltimore) Evening Sun on July 17, 1943, first calls out Starrett’s use of wit in his sonnets. Then he notes:

But like most wits, he has a very pretty vein of sentiment as well. He has a feeling for forms and flavors of the past, especially for our immediate past of ten to 50 years ago, which is so rapidly becoming a closed volume of world history. In “221B” he catches the aroma of immortality that lingers around Holmes’ flat in Baker Street.

A lonely hansom splashes through the rain.

The ghostly gas lamps fade at twenty feet.

Here, though the world explode, these two survive,

And it is always eighteen ninety-five.

So far as I’ve been able to tell, Hart is alone in recognizing the poem’s charms. Even William Rose Benét, who wrote the introduction to Autolycus and noted that Starrett was a founding member of the BSI, says nothing about the sonnet to Sherlock.

The fact is “221B” wasn’t written for the masses. It was created for Edgar W. Smith and those like him who love Holmes and the world he represents. It would be up to the Sherlockian world to make sure the sonnet didn’t fade into the yellow fog of night.

In Chapter 8, 221B finds two advocates: Edgar W. Smith and Basil Rathbone.

‘221B’ Chapter Index

Chapter 1: Introduction and Prologue: ‘Where it is always 1895’

Chapter 2: 'So they still live for all that love them well'

Chapter 3: ‘Some of the most dramatic months… of contemporary history’

Chapter 4: ‘Here dwell together still’

Chapter 5: ‘He has done many little things for me’

Chapter 6: ‘A wider circulation’

Chapter 7: ‘Part of a slim volume’

Chapter 8: ‘This poem by my good friend’

Chapter 9: ‘Something remains of London in 1895’

Chapter 10: What is it we love about ‘221B’?

Chapter 11: Afterthoughts and Acknowledgments

Want to chat about this blogpost? Join us at the Studies in Starrett Facebook page: