Sherlock Holmes Comes Home

Private Life Chapter 5: The British First Edition

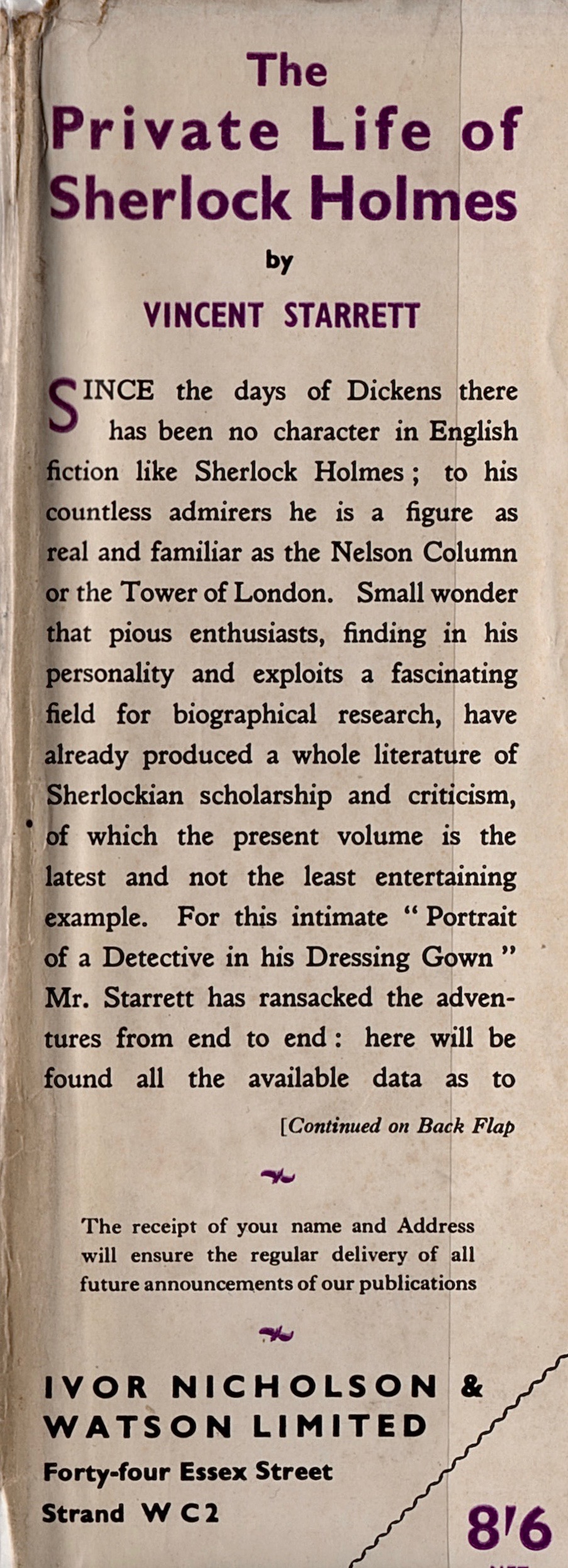

Vincent Starrett created the market for books about Sherlock Holmes in the United States when The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was published in 1933. But when the British edition came out one year later, Private Life was just one of several publications about the Baker Street detective available to the budding Holmesians in Great Britain.

Mgsr. Ronald Knox’s 1911 ground-breaking essay “Studies in The Literature of Sherlock Holmes,” had been republished a couple of times, most recently (at this point) in Knox's Essays in Satire published by Sheed and Ward of London in 1928. (It has been reprinted widely since.)

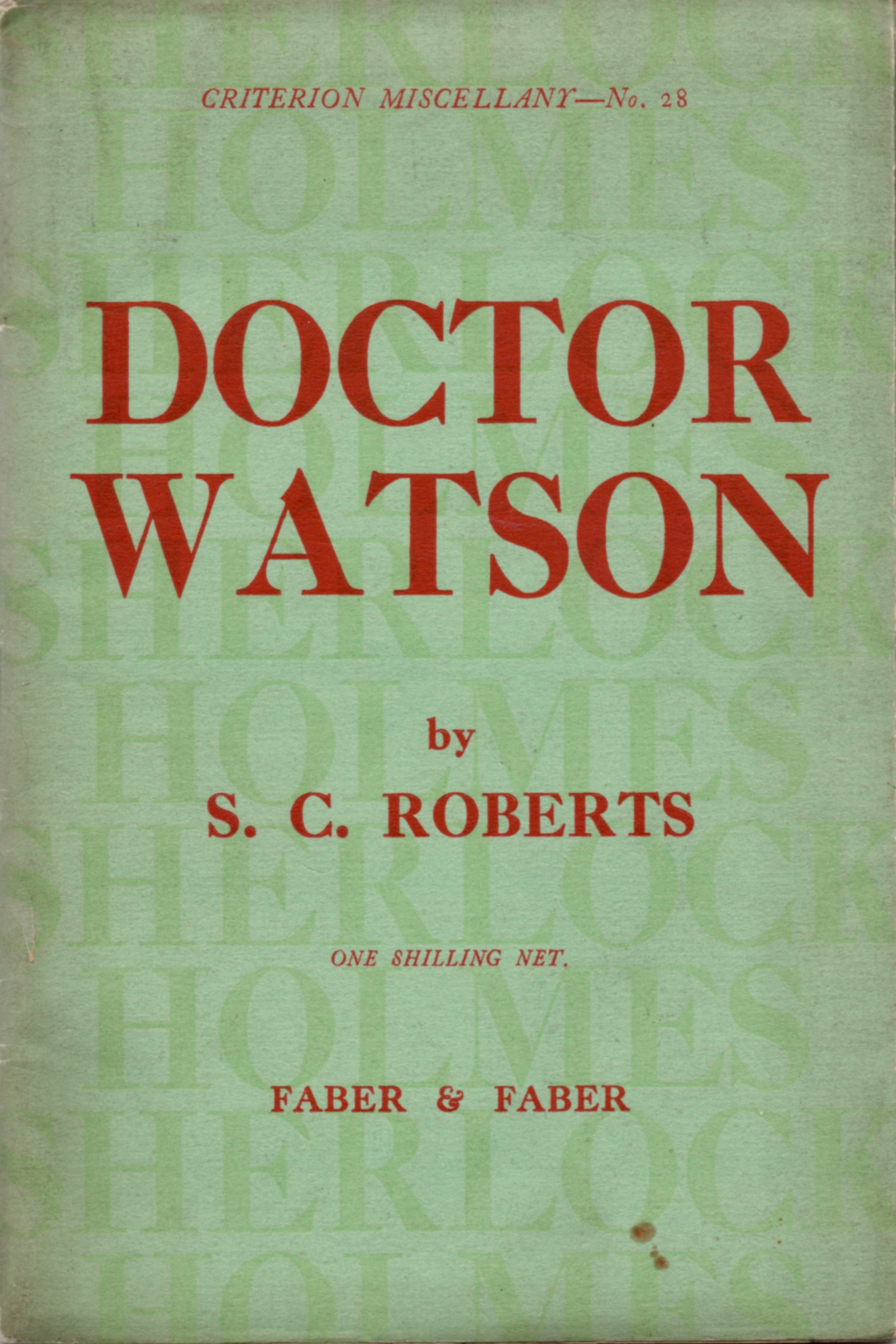

Three years later, S.C. Roberts’ Doctor Watson: Prolegomena to the Study of a Biographical Problem, with a Bibliography of Sherlock Holmes was produced as a pamphlet by Faber & Faber of London. Roberts was a Dr. Johnson scholar, so to turn from Boswell to Dr. Watson was not a great shift. His 30 pages of analysis about the good doctor’s life and history was fully in “The Game” and is delightful, even after all these years. It’s followed by a two-page bibliography of Holmes’ publications, which anticipates Starrett’s own bibliography in Private Life.

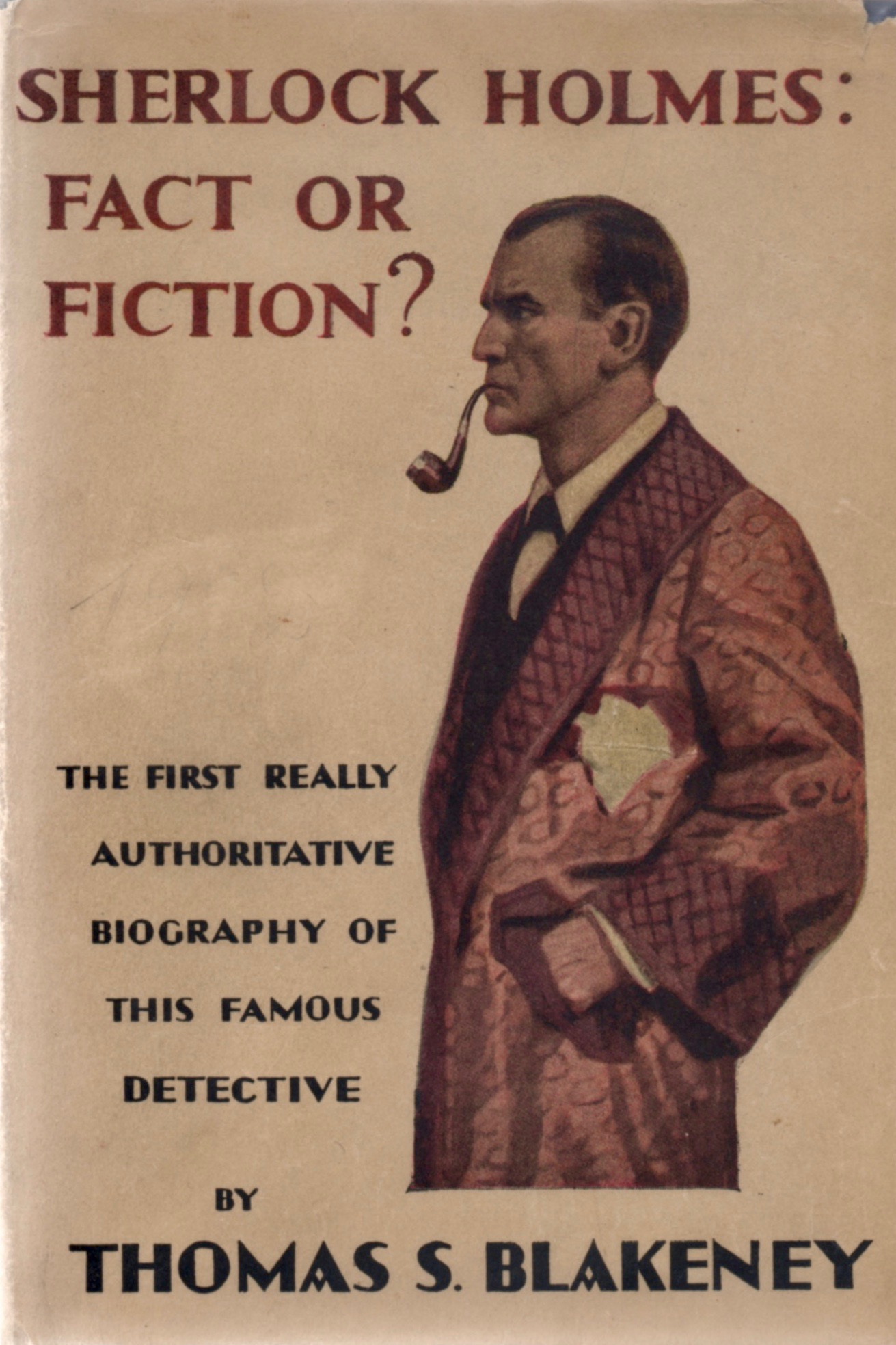

The same year, 1932, saw November’s publication of a more lengthy work of criticism by Thomas S. Blakeney, Sherlock Holmes: Fact or Fiction? As you can see from the dust jacket, publisher John Murray (who had published most of the Holmes books in England) promoted Blakeney’s work as “The first really authoritative biography of this famous detective.” To encourage the belief that it is a continuation of the Holmes saga, Murray created a book that, in size and jacket design, is wholly complementary to its set of Dr. Watson’s chronicles. Like Roberts, Blakeney never mentions Conan Doyle and gives himself over completely to discussing Holmes, Watson et al. as living men whose lives are worthy of explication.

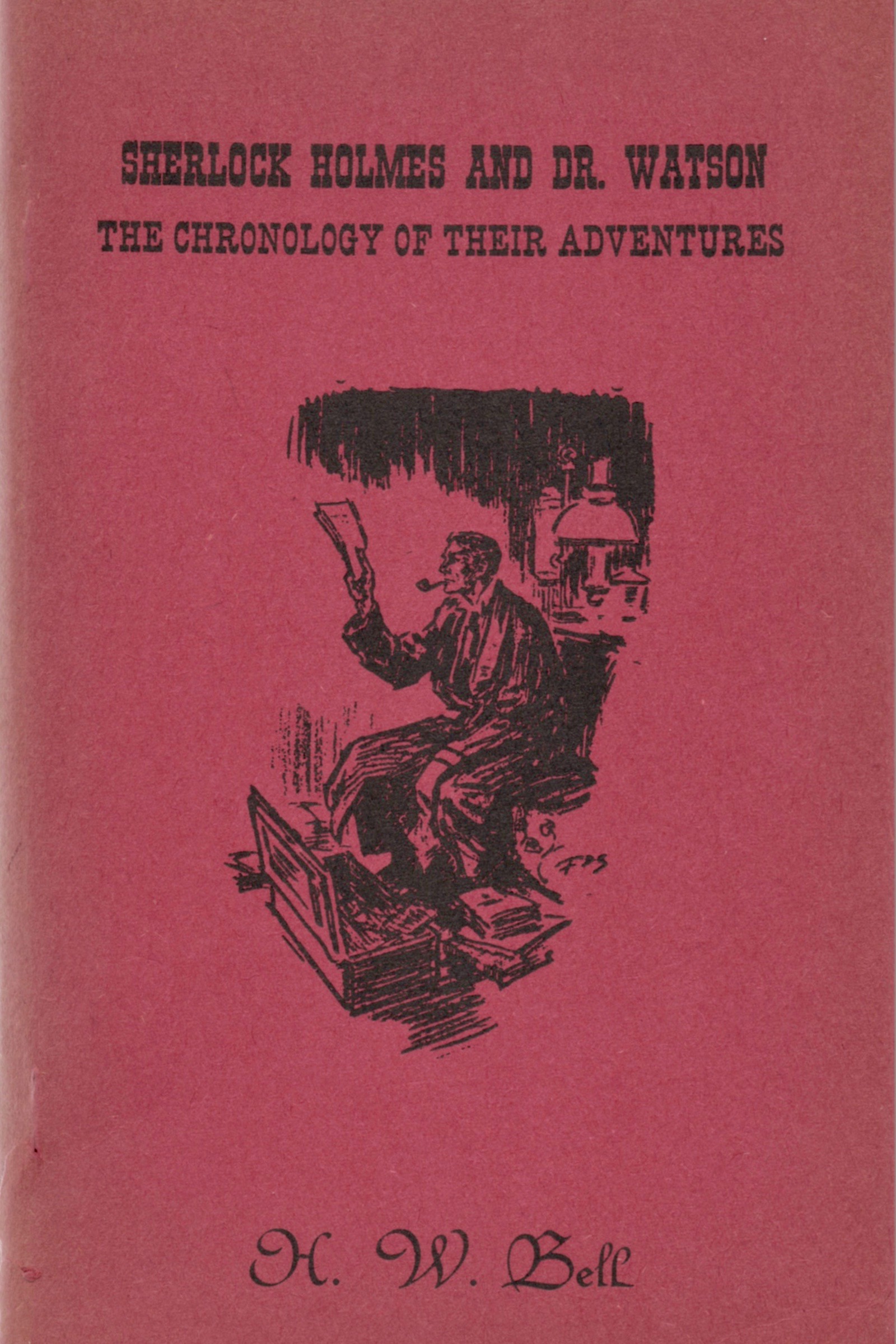

There was also H.W. Bell’s Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson: The Chronology of Their Adventures, published in 1932 by Constable & Co. of London. (I don't own a copy of the original, but I do have the 1953 Baker Street Irregulars reprint.) Bell, an archaeologist, dug through the canon to produce the first attempt at a comprehensive chronology, an activity that has captivated and confused commentators ever since.

As a result of these works, Starrett’s Private Life had to compete with a small but steadily growing batch of books for the niche Sherlock Holmes market. And unlike American critics, the British reviewers had other examples to use when judging the value of Starrett’s book.

Nevertheless, Starrett was pleased with the reception that Private Life received. Before we get to the reviews, let’s look at the book.

Title page of the first British edition.

The British First Edition: A Description

Ivor Nicholson & Watson, Limited, London, June 1934. First edition. Hardcover 8 ¼” X 5 ¼”. vii, [vi], 199pp.

Cover: Light blue cloth over boards.

Spine: THE/PRIVATE/LIFE OF/SHERLOCK/HOLMES; VINCENT STARRETT at head. IVOR/NICHOLSON/AND/WATSON at tail.

Dust Jacket: THE PRIVATE LIFE/OF SHERLOCK HOLMES in white at top of cover; VINCENT STARRETT in violet at bottom, with a violet bar underneath. Illustration of the entrance to 221B by an uncredited artist.

Spine: THE PRIVATE/LIFE OF/SHERLOCK/HOLMES BY VINCENT STARRETT at head in violet ink. IVOR/NICHOLSON/AND/WATSON at tail, also in violet with bar underneath as on dj cover. Uncredited illustration of Holmes in deerstalker with hand at chin in contemplation standing next to an oil lamp.

Dedication: “To/William Gillette/Frederic Dorr Steele/And/Gray Chandler Briggs/In Gratitude” (Same as in the American first.)

Thoughts on the First British Edition

The dust jacket cover with its romantic image of 221B Baker Street.

I love this dust jacket, and prefer it to its American cousin. The cover illustration of the street entrance to 221B captures Starrett’s affectionate description of Holmes’ home. I can easily see Holmes and Watson bursting out of that door and racing down the street to catch a cab as they seek their next adventure.

And the illustration of Holmes on the spine, while stuck in deerstalker mode, nonetheless gives us a Holmes in full contemplation of a problem. It is just the kind of illustration that would entice a reader to pull the book off the shelf and consider its purchase, which is, after all, the purpose of a dust jacket.

I wish I knew the artist who drew the cover and spine illustrations. I can find no name anywhere on the jacket.

The use of the violet or purple (hard to tell with all the fading) ink for Starrett’s name and wording on the dust jacket’s spine anticipates the infusion of purple that will come when the book is revised, updated and republished in 1960 by the University of Chicago.

The text and illustrations are largely the same as the text in the American edition.

The dust jacket spine could not avoid the “detective in deerstalker” trope, but I do like the image of Holmes in contemplation.

A few minor changes to note:

The acknowledgment page cites the British publication history of the stories as they appeared in London. The American first had the U.S publication history.

In the text, there is one deviation from the American first, and it comes in the essay “The Return of Mr. Sherlock Holmes.” Remember last time when we showed you the changes Starrett made by hand in the book he inscribed to Eddie Liegler? Starrett twice changed the date of October 1904 to December on the same page. Here, that change is incorporated into the text.

New plates were used by Ivor Nicholson and Watson and as a result, the book is a little slimmer than its American cousin: 199 pages in England, compared with 214 in the States.

The image of William Gillette as Holmes drawn by Frederic Dorr Steele is missing from this edition. It was stamped on the cover of the first American and printed on the FEP. Perhaps it was seen as "too American" in its influence, since both the actor and the artist are from the States and Paget’s influence was far more prevalent in England.

By the way, how cool is it that the British edition was published by a firm with Watson in its name?

The final section of the book, “Studies and Reviews of Mr. Sherlock Holmes in Books and Periodicals, including Parodies and Burlesques, and other Sherlockian Matters of Interest to the Collector,” is the same as the American first. But here, the notes on the British entries seem to carry more relevance.

Of H.W. Bell’s Chronology, Starrett says, “A fine volume of fantastic scholarship.”

T.S. Blakeney’s Sherlock Holmes: Fact or Fiction? rates a note as “The biography of Sherlock Holmes by a leading Holmes specialist.”

And Doctor Watson by S.C. Roberts receives an approving nod: “A gorgeous serio-comic biography of the good Watson.”

A Final Thought

The image of William Gillette as Holmes drawn by Frederic Dorr Steele is missing from this edition.

As I mentioned earlier, Starrett was delighted by the fact that his book was given a British printing. None of his mystery novels had crossed the pond to Sherlock’s native country (although a few of Starrett’s novels would make an appearance in the French bookstalls). Here’s what he had to say in his memoirs, Born in a Bookshop, about Private Life and its British appearance.

“This work, my best-known book gave me for the first time an international audience and made me a decent reputation in England. British reviewers expressed polite surprise that the first biography of Holmes should have come from America.”

That makes a nice segue into our next week’s posting.

In the United States, Macmillan published Private Life as part of its biography line of books. Ivor Nicholson and Watson saw things differently, and classified Starrett’s book in with its crime fiction.