A Modern Book of Wonders: A forgotten Starrett book

"The Mechanical Man" was also known as 'Willie Vocalite.' He can 'smoke cigarettes, operate a vacuum sweeper, turn lights on or off and perform numerous other simple tasks.' Willie was an invention of the Westinghouse company and more about him is available at the cyberneticzoo website. He is also one of the "amazing" and "marvelous" items featured in the volume Starrett edited.

When I was growing up and sneaking science fiction short story collections into the house, one name that popped up with regularity was Fritz Leiber. His tales were heavily anthologized and with good reason: he was a great storyteller whose work stands up well today. In particular, his short story, “The Girl with the Hungry Eyes,” detailing a modern day vampire who wasn’t after blood but your soul, had a profound impact on my teen-aged mind.

So it was with a start that I found Leiber’s name mentioned in passing in one of Vincent Starrett’s more forgettable works, A Modern Book of Wonders: Amazing Facts in a Remarkable World. An ungenerous person might claim that Leiber’s participation is one of the few remarkable items in this otherwise forgettable work.

For Starrett, the book is one he never mentioned and it lacks any memorable qualities. Except for the introduction, the book was largely a clip job and it's easy to see why he chose never to acknowledge it.

So if you have ever scratched your head after running across this little volume in the dusty bin of used bookshop, you need to wonder no longer.

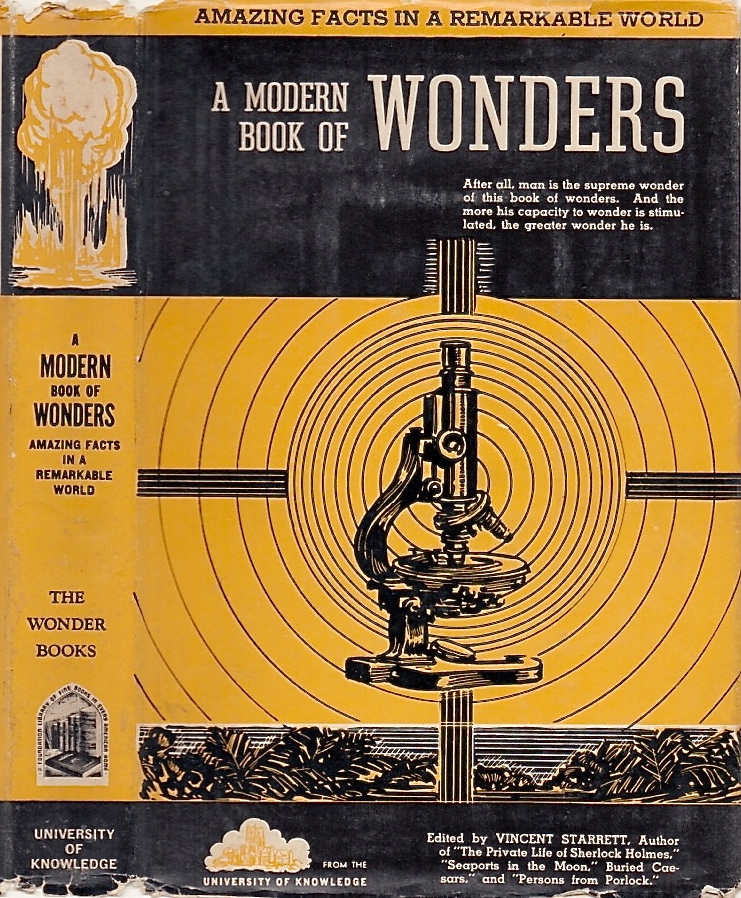

Dust Jacket to Volume 18 of the "Green Imperial Edition." Starrett edited A Modern Book of Wonders: Amazing Facts in a Remarkable World. Don't you just love the breathless way in which the dj has become a billboard for the series? And who would not want to own the "Green Imperial Edition"? Sounds pretty darned fancy to me.

A Modern Book of Wonders: Amazing Facts in a Remarkable World was produced by the “University of Knowledge, Inc.” in Starrett’s adopted city of Chicago in 1938, and went through at least a couple of reprints in 1941. Starrett edited Volume 18 in a 24-volume series that went by the general name of The Wonder Books.

In those pre-Internet days, encyclopedias of useful, odd and unexpected information were pretty common.In the upper echelon was the Encyclopaedia Britannica, leather bound and intimidating with its formal language and authoritative entries. It practically begged for silent respect while reading. No self-respecting library of its day lacked a complete set. Stepping down the information food chain were sets like those from Funk & Wagnalls, which in my childhood could be purchased one volume at a time from the local A&P supermarket for $4 or so.

The Wonder Books were several steps down the ladder from Funk & Wagnalls, largely consisting of corporate press releases, odd and unusual news brief items that appear to be copied from newspapers or magazines, all heavily dosed with a “gee-whiz” style of writing. The breathless advertising copy promised “9,216 pages, 3,000,000 words, 7,000 pictures. Everything you want to now about the fascinating secrets of Science, Art, History, Industry, Nature, Travel, Music, Literature.” Volume one was The Earth Before Man and the series ended with Marvels of Asia and the Orient.

Starrett managed his own breathless comments in his Preface for Volume 18.

What is that illustration stamped on the cover? An atomic bomb mushroom, perhaps? This book was printed four years before the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Perhaps in 1941 it was possible to see the bomb as part of a "marvelous world."

Naturally, he starts with an image from literature, of Alice falling down the rabbit hole. “One recalls with happiness the bookshelves on the way down (we never did find out what books they held) …”

While acknowledging that the volume is not an Alice story, Starrett promises “It is your adventures in a modern wonderland; and mine; and I will say this about it, without a quiver of an eyelash: it is filled with more wonders than Lewis Carroll ever dreamed of, and some, I think, that would have caused that admirable dreamer to open his eyes in surprise, and perhaps raise his ecclesiastical eyebrows in disbelief.”

That’s heady stuff for a volume that features articles on cannibalism and the secrets of snake charmers.

The contents feel like a walk through a higher grade of Ripley’s Believe it or Not: “Mr. Robot,” and the “Incredible Power of Animals,” with “Happy Accidents of Science,” next to “Marvels of the Human Body.” Rounding out the volume are chapters on subjects that seemed to have a hold on the fantasist in Starrett: “Hypnotism, Prophecy, and Telepathy” and “Conquest of Time and Space.”

There is even a mention of the man from 221B Baker Street, in the section on “Scientific Crime Detection.” After discussing the use of various lab tests, Starrett notes: “If Sherlock Holmes were a present-day character he might profit by modern methods.”

The books are occasionally still to be found today, collecting dust in the lower shelves of used bookstores and the odd offering on eBay or Amazon.

As for Starrett’s relationship with Leiber: That remains a mystery for now. The two were residents of Chicago at the same time, so it’s no surprise that they knew one another.

What role Leiber had in this volume is a little enigmatic, as the final lines in this column will make clear. Leiber does not rate a mention in Starrett’s memoir, Born in a Bookshop, so the association could not have been a strong one.

However, it should be noted that Leiber was enough of a Holmes fan to pen “The Moriarty Gambit,” a pastiche that was included in the 1965 anthology West by One and by One.

Here’s the mention of Leiber that ends Starrett’s preface:

I should feel indeed that my task were incomplete if I did not pay tribute to those who have assisted me in presenting this volume in such an interesting and readable style. To Fritz Leiber, Jr., Charles Paape, Naomi Rabe, Charles L. Hopkins, and Louis Herman I extend grateful thanks and appreciation for their industrious researches and editorial contributions.

Final thoughts: Was Naomi Rabe related to Bill Rabe, the Michigan BSI and higher education PR madman?

And while we’re at it, was Charles L. Hopkins related to Stanley Hopkins of “The Adventure of the Golden Pince-Nez”?

We can but wonder.

The endpapers to the Wonder Books are stuffed with historic, legendary and thrilling images.