A.K.A. Vincent Starrett

The many names of Vincent Starrett

He was born Charles Vincent Emerson Starrett.

During the course of a long career, he was known by many names to his family, his readers and his friends. If you’re going to collect Vincent Starrett, you need to know the names you’re looking for.

Let me introduce you to the many names of Vincent Starrett.

For more about this book and it's tender, sad story, go here.

Charlie

Growing up, he was known as Charlie, or Charles. His siblings called him Charlie well into his adult years. Younger family members, who came along after he had achieved some fame as a writer, knew him as "Uncle Vincent." (He had no children of his own.)

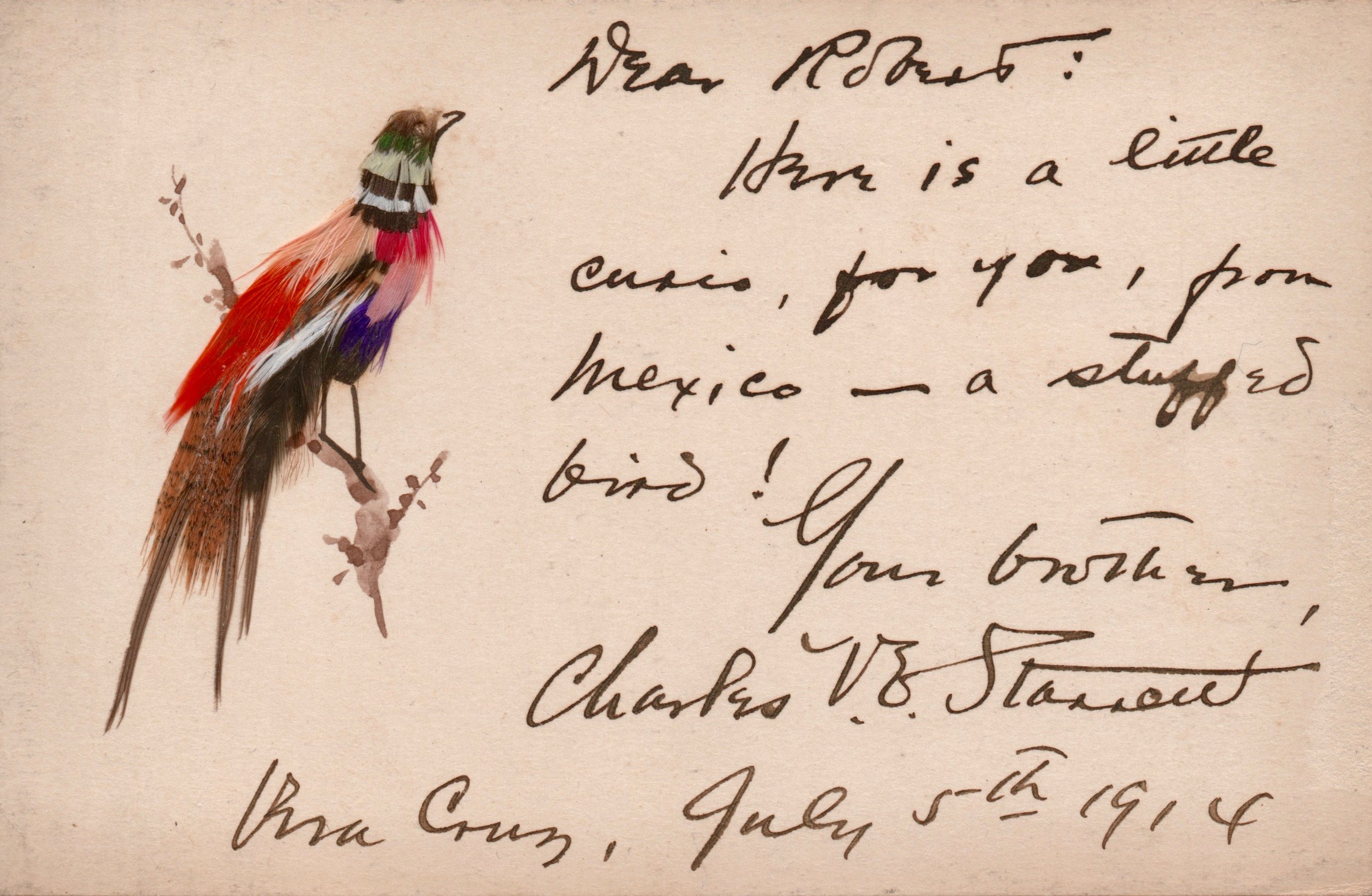

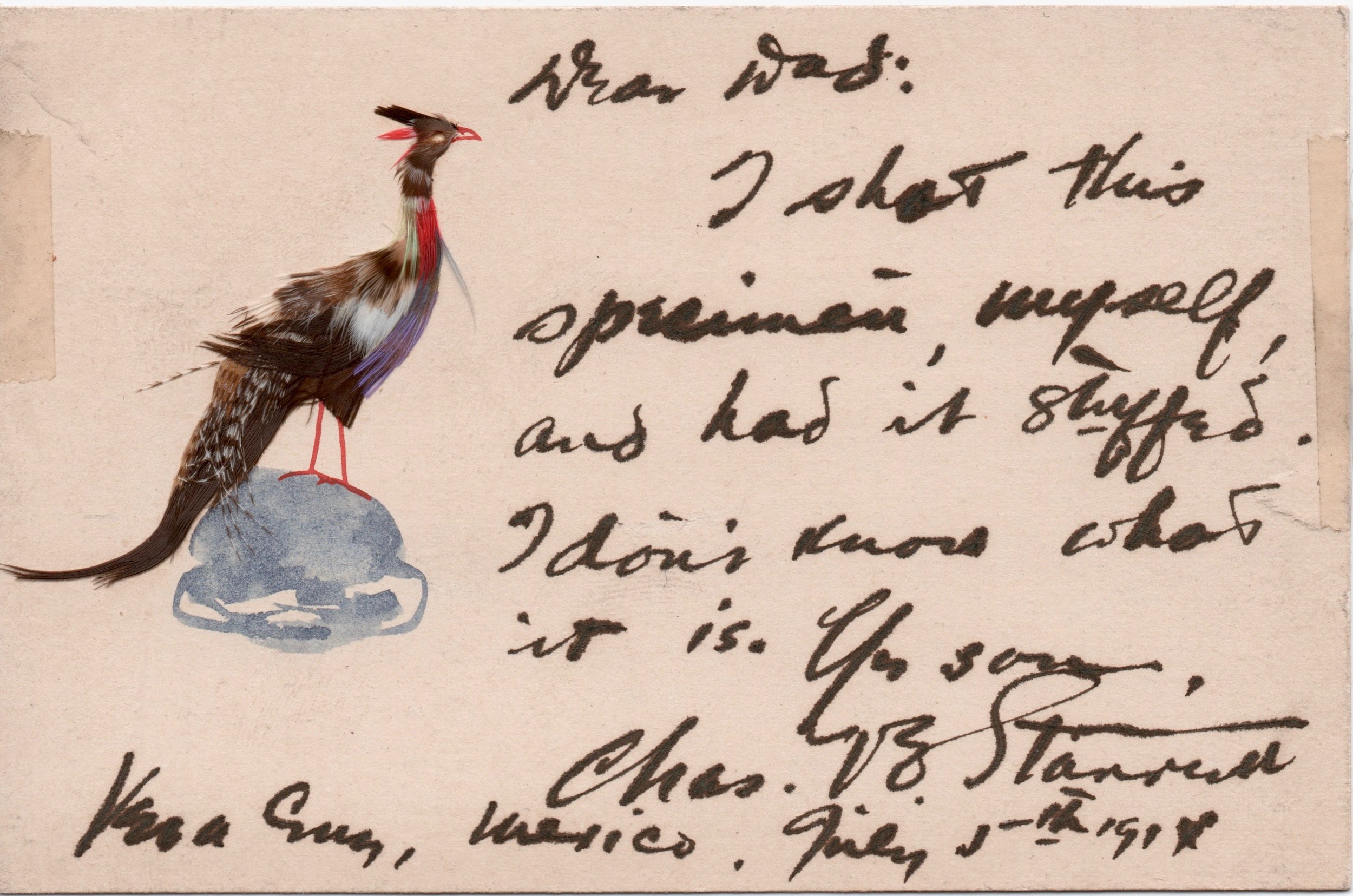

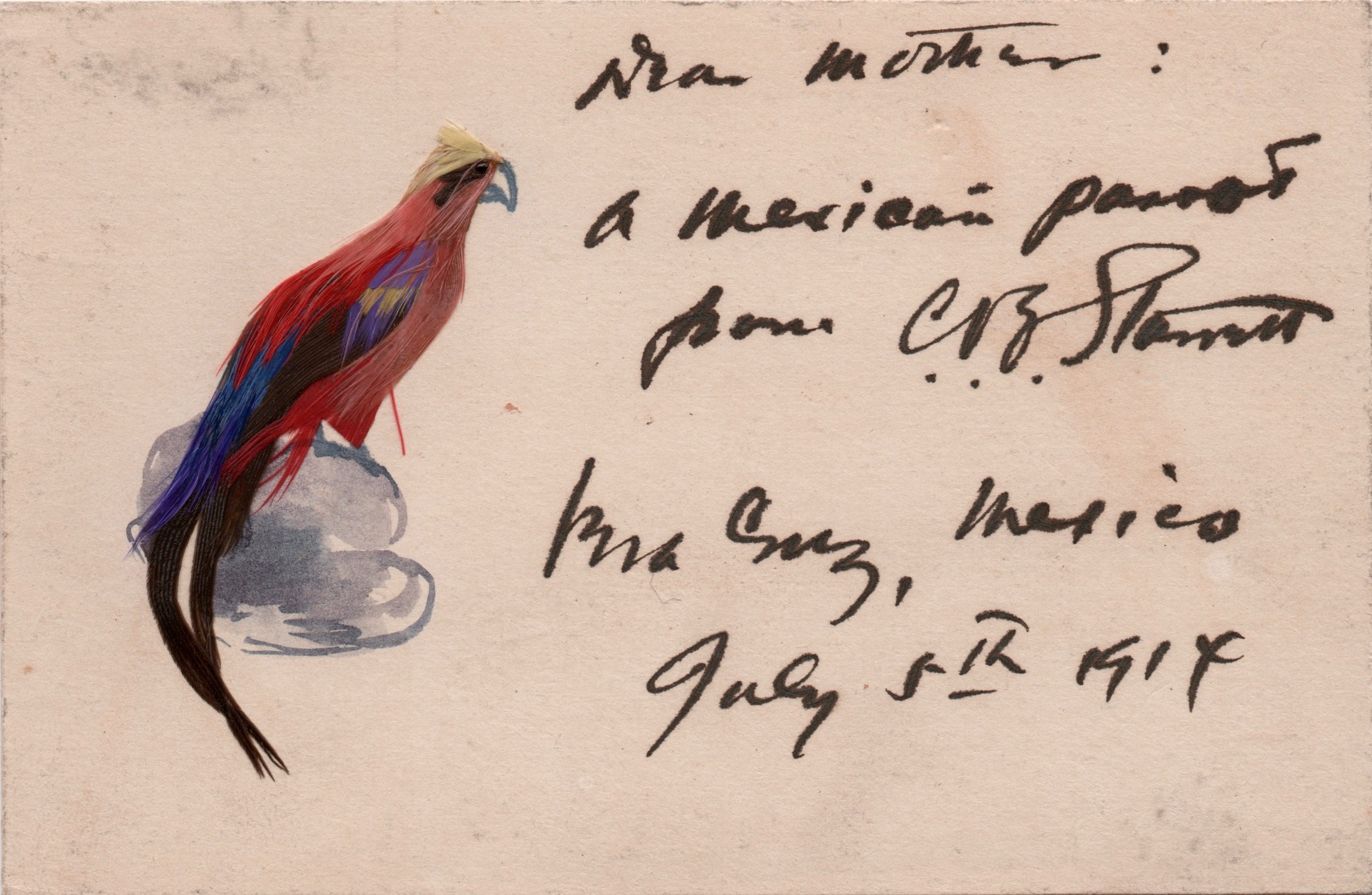

I own a few postcards sent by Starrett from the Mexican civil war of 1914-15 to family members that are signed “Charlie.”

But to my mind, the most touching example of this family name is the inscription to his mother in the 1922 book of his poetry, Banners in the Dawn.

(If you haven't read the story behind this copy of Banners, let me suggest you take a few minutes to visit this posting.)

Charles V.E. Starrett

Although the files of the Chicago Inter-Ocean and the Chicago Daily News are not easily accessible, there’s evidence to suggest that when Starrett left high school to become a newspaper reporter, he used Charles V.E. Starrett as a byline.

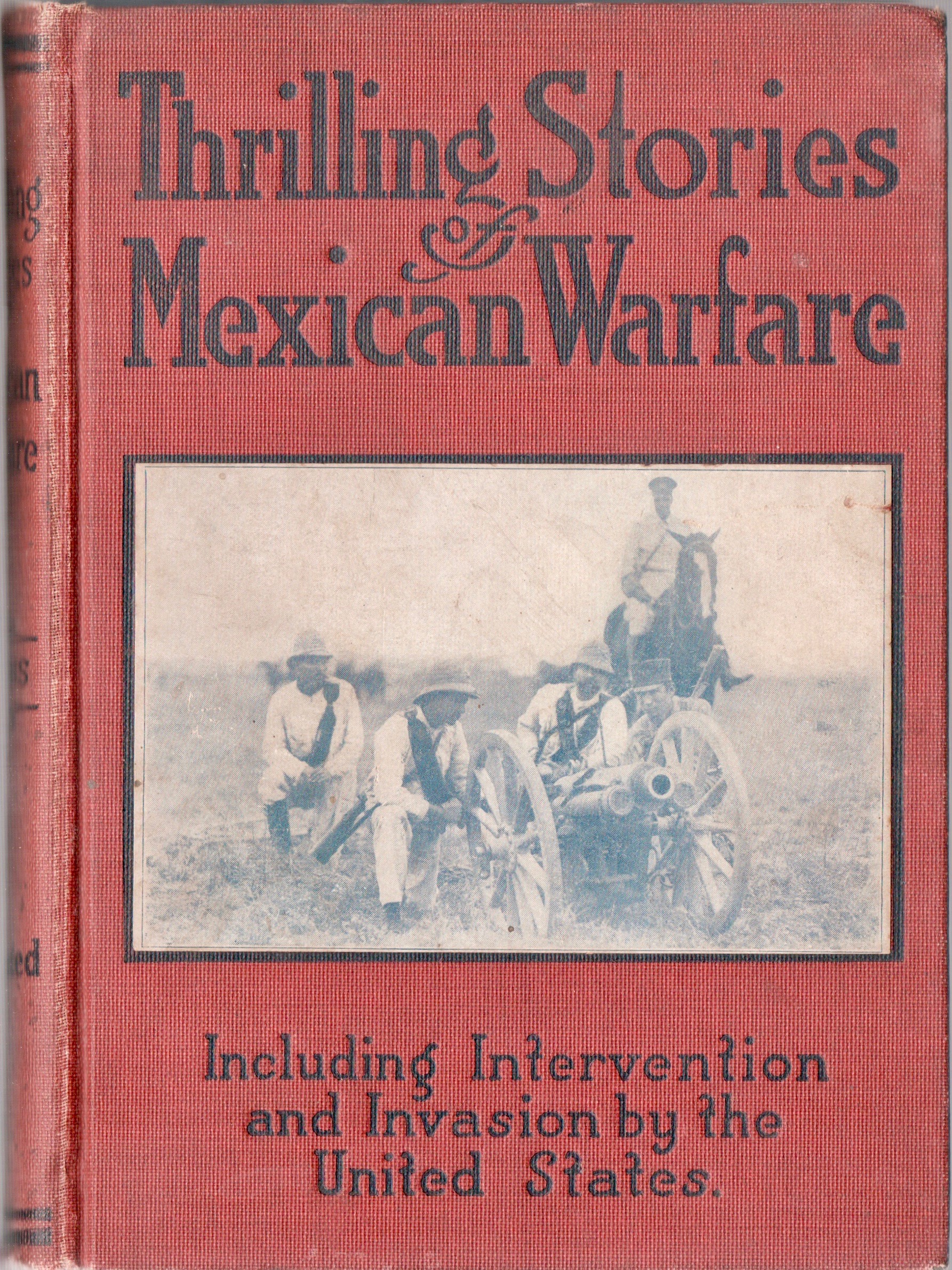

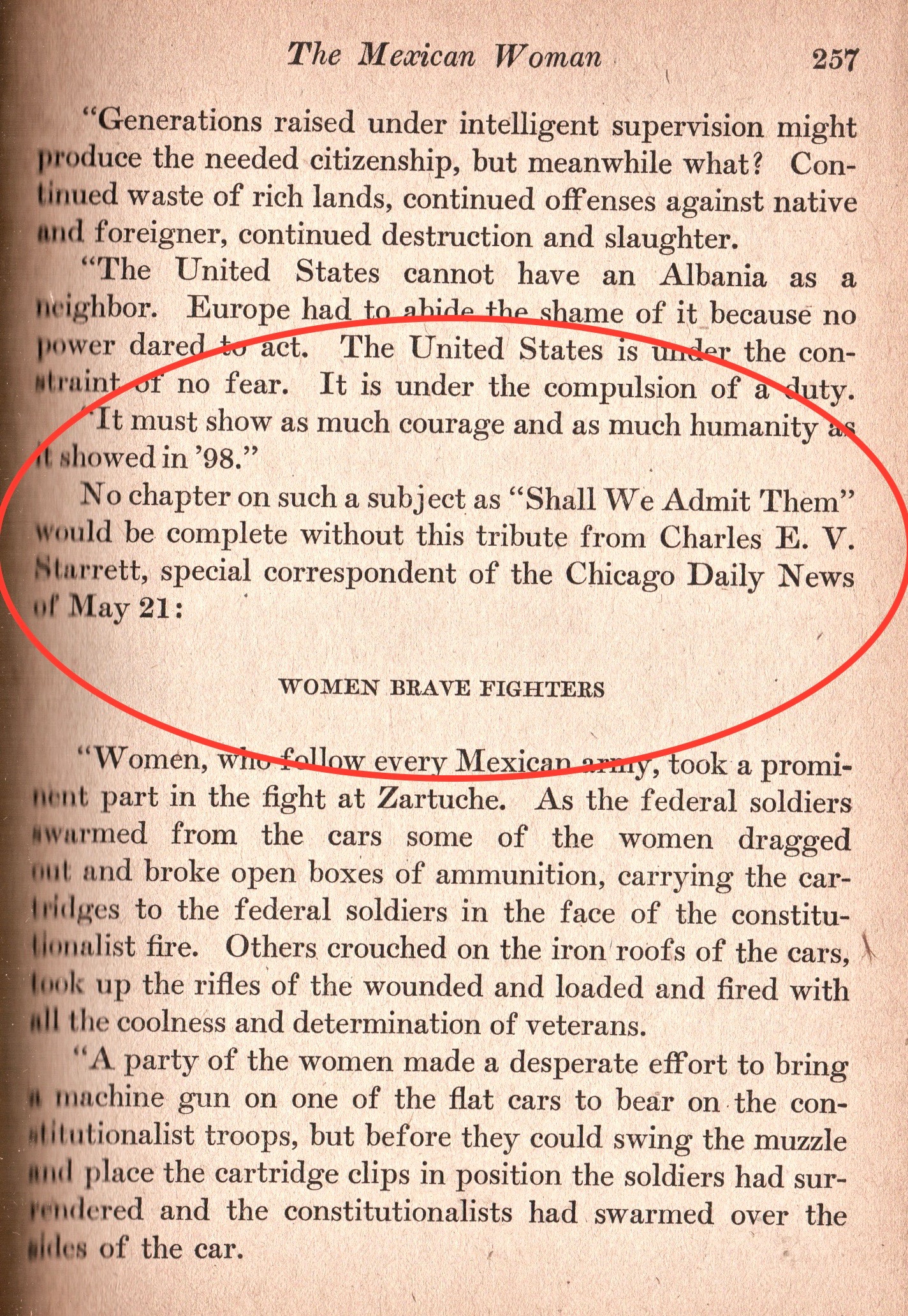

Here’s a reprint of an article he wrote as a reporter during the Mexican civil war of 1914-1915 with this variant. The article was reprinted in a cheaply published edition that tried to capitalize on the public’s great interest in the conflict.

Note that two middle initials are transposed: Charles E.V. Starrett instead of Charles V.E. Starrett. Just goes to show you how rushed the whole book project was and why the world needs good copy editors.

I’m also including some cards he sent back home from the war zone to his family that used his byline. The cards are quite lovely, with the birds on each made from real bird feathers.

While showing these on the Studies in Starrett Facebook page, I had wondered why Starrett used this formal name when writing to his family. In thinking about it, I wonder if he wasn't showing off a bit, letting the folks back home know he was a big shot war correspondent.

At any rate, the cards are little works of art and show how much Starrett cared about his family, regardless of what name they used for him..

There’s also a four-page piece by Charles V.E. Starrett dedicated to David Ker, one of the last “boy’s adventures” writers whom Starrett admired. The article appears in the Jan. 30, 1915 issue of The Editor: The Journal of Life for Literary Workers. I've seen this article but don't own a copy.

Yet.

And I suspect there are articles from the early to mid 1910s that bear this name. It will be fun hunting them down.

Charles V.E. Starrett also shows up in formal occasions, like the 1940 divorce filing against his first wife, Lillian Hartsig. This clip is from the Feb. 17, 1940 issue of the Reno Gazette-Journal in Reno, Nevada.

From the Feb. 8, 1918 issue of Reedy's Mirror, where many of Starrett's earliest essays appeared first.

Vincent Starrett

As a writer of essays, book reviews, mysteries and other stories, he took the name Vincent Starrett, and that soon replaced the much longer Charles V.E. Starrett as his newspaper byline too.

It was a good move. Vincent carried with it an air of sophistication that the more common Charles lacked.

A "Vincent" needed to be heeded.

A "Charles" could be chucked.

I’m not sure exactly where this variation on his name was first seen. It was the name that he used when writing some of his earliest essays for Reedy’s Mirror in 1917 and 1918. Starrett cites Reedy's as the place where he became a professional writer.

It was also under this name that his Jimmie Lavender and other mystery stories were published in pulps like True Detective and Short Stories in the late 1910s.

By the 1920s, the other variants on his name largely faded from public view, although Vinpenny showed up as his alias for light verse published in newspapers for many years to come.

Starrett, or at least his poetic alias, made it on the dust jacket cover of the verse anthology, Column Poets, published in 1924.

Vinpenny

As an aspiring poet, Starrett had many outlets for his work, including the daily newspapers in Chicago, where poetry was a regular feature. Less common were poets who used their own names for column submissions.

For example, early Chicago Sherlockian Jay Finley Christ wrote often about Holmes topics for the Chicago Inquirer column “A Line O’ Type Or Two,” under the name Jay Finch.

Likewise, Starrett’s poetry was often attributed to Vinpenny. This name was exclusive to his lighter, newspaper verse, although it made its way into at least one book, the 1924 collection, Column Poets, as you can see from this very handsome, art deco dust jacket.

It is one thing to have a cute nickname when your verse is presented in a daily newspaper. But when Starrett submitted more serious work to major magazines, like Poetry or The Saturday Evening Post, he preferred to have it published as by Vincent Starrett, and not Vinpenny. While "building your own brand" was not a concept in the 1920s. creating name recognition for your talents was a well-known practice even then.

Starrett’s poetry days were largely over by the 1940s, but I did recently notice the “Vinpenny” name popping up again on a poem published in the May 21, 1939 Wisconsin State Journal.

(Starrett’s desire to find himself at a lighthouse “battered by the sea” with a room full of books and “Ginger Rogers in for tea,” is one that is shared by others. And since we're living out our dreams, I might substitute Myrna Loy for Miss Rogers, thank you very much.)

Starrett's poetry showed up in the strangest places, from socialist workers journals to Weird Tales Magazine to the more exclusive poetry publications. His most prolific era was the 1910s to the 1940s, but odd verses continued to show up decades later.

For the most part, he published poetry under the Vincent Starrett name in later years.

When Starrett died, friend Michael Murphy memorialized this moniker by printing an old tribute to Vinpenny from Roy Franklin Dewey, a Chicago bookdealer and occasional poet himself. (To further confuse the matter, Dewey wrote under the name Lucian Taylor.) Dewey's tribute to Starrett is included here.

I’ve not been able to find an origin story for the name Vinpenny. Clearly "Vin-" comes from Vincent Starrett, but why "penny"? The world may never know.

Poetry from The Wave by Starrett, but attributed to Stephen Huguenot.

Stephen Huguenot and Edgar Savage

in addition to Vinpenny, Starrett used two other nom de plumes in his poetry and short stories: Stephen Huguenot and Edgar Savage. As far as I can tell, both appeared first in The Wave, the little literary magazine Starrett edited as his contribution to the Chicago Renaissance, the movement that swept through that city in the first few decades of the last century. (NOTE: Stephen Huguenot's earliest appearance as the author of short stories was in The Double Dealer, another little magazine, also published in the early 1920s.)

As The Wave's editor, Starrett had at least one contribution to every issue. So it’s not surprising that he used these names to cover the fact he was also choosing his own poetry for the little journal. It didn’t happen often. For this information I am indebted to Charles L.P. Silet and his article, “Vincent Starrett’s Pseudonymous Poems in ‘The Wave’ ” in the Winter, 1981 issue of The Great Lakes Review. Silet finds five poems under Starrett’s name, two in the first issue (January 1922) as Edgar Savage; and three others under Stephen Huguenot, one in the January 1922 issue and two more in the June 1922 number. (There were only eight issues of The Wave, with Starrett editing all but the last.)

Silet believes Starrett used these names because he was still uncertain about his skills as a poet. as he correctly notes, “The prose he signed; the poetry he did not.”

Starrett outed himself in his memoirs, Born in a Bookshop, as using the two "alter egos." He doesn't say why.

Copies of The Wave are hard to find and very expensive. I have only three issues and just one has poems using the Huguenot name. This is not, however, the last time we will hear of Mr. Huguenot.

Autolycus

Speaking of Stephen Huguenot, I discovered the name being used occasionally in The Chicago Tribune in the 1940s, a few decades after The Wave had been swept out to the ocean. Starrett contributed occasional “filler” items for the Tribune, as part of an irregular column called “A Literary Anthology.”

The column was made up of short anecdotes or aphorisms, the kind of thing that would be turned into an internet meme today. Each column was signed by Autolycus, whom he defined as “A snapper up of unconsidered trifles,” a line from Shakespeare's The Winter's Tale (Act 4, Scene 3: "My father named me Autolycus; who being, as I am, littered under Mercury, was likewise a snapper-up of unconsidered trifles.")

Other sources note Autolycus was a Greek God famed for trickery and theft.

Starrett was so intrigued by the name that he titled his most famous poetry anthology, Autolycus in Limbo. Faithful readers will remember it was the first book to publish Starrett’s sonnet, “221B.”

Here is an example of "A Little Anthology" from the November 17, 1946 issue of the Tribune. I especially like it because it is not only signed Autolycus, but has a pearl of wisdom each from Stephen Huguenot, and Sherlock Holmes.

And did you notice that just under the Holmes quote, there's one from 18th century poet Walter Savage Landor? Savage. Wonder if that's were Edgar Savage's last name came from? Just a guess.

This name is the result of a "playful printer."

Charles Vincent Starrett

One of Starrett’s most unusual books was Et Cetera. Published in 1934 by Pascal Covici of Chicago, Et Cetera was a collection of never-before published or rarely seen fragments by authors like Walt Whitman, Andrew Lang, Arthur Machen, Stephen Crane and Lord Dunsany.

The book was limited to 625 copies and most of them clearly state it was edited by Vincent Starrett. But as you can see here, some carried the name Charles Vincent Starrett.

BTW, this illustration comes from copy number 45 of Et Cetera. I have two other copies, Nos. 216 and 445, that say "Edited by Vincent Starrett." Perhaps those with lower numbers were bore the variant name?

In Charles Honce’s bibliography, Starrett explains this curious circumstance as the work of “a playful printer.” Sounds more like a printer's error to me.

Starrett gravestone at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

There is one other place that I have found this variation on Starrett’s name: his headstone.

As you can see here, he will forever be known at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago as Charles Vincent Starrett.

Vincenzio

To Christopher Morley, he was always, “Vincenzio.”

That’s actually not true, but it is a nice play on the opening line from “A Scandal in Bohemia.”

Starrett and Morley addressed each other formally in their early correspondence, but soon became more familiar as time and shared interests built a tighter bond. Vincenzio became the nickname Morley used for his friend, and he was Vincenzio until Morley passed away in 1962. It was the name that came in letters bearing news of the Irregulars and their antics for more than 20 years.

Perhaps it was the name Starrett enjoyed seeing the most.