Brothers of the Book

Pierrot and Pirates!

By way of apology

You’re probably wondering why I’m standing in the middle of Studies in Starrett World Headquarters while on a pair of skis. I’m doing this to illustrate how far over my skis I’m going to be while discussing an odd little book of poetry that recently joined the shelves. I will describe the book and its Starrett connections despite the fact that 1) I am far from qualified to discuss poetry; 2) I know only what the interwebs can tell me about the character of Pierrot; and 3) it wasn’t until a week ago that I paid any attention to Laurence C. Woodworth, who figures prominently in the tale.

With that full disclosure, I will get off the skis and on to today’s post.

Rathbone, Eliot and Woodworth

(But Not In That Order)

Five years before his death, Vincent Starrett published an extensive feature story in the Chicago Tribune that runs across several pages in the Sunday magazine for August 10, 1969. Starrett was 82 at this point and most of the features he wrote were reminiscences or reworkings of earlier efforts. (More on that later.) Regular readers will no doubt recognize this page from a recent discussion of Starrett’s relationship to poet T.S. Eliot.

The first page of Starrett’s August 10, 1969 feature story. Although the photos refer to Rathbone and Eliot, the story starts with two others: Don Quixote and Laurence Woodworth.

If you tried to read the accompanying newspaper clipping, you would have noted that despite the headline, Starrett does not start by discussing Sherlock Holmes, Basil Rathbone or Eliot. Instead, he starts to figuratively roam around his bookshelves, beginning with a few paragraphs about the enduring popularity of Don Quixote. The tale of the old knight “still outsells, especially during the Christmas season, quite a few so-called masterpieces of the moment.” Starrett then pushes right into an extended memory of Laurence Conger Woodworth. To him, this shift makes sense, although the transition is lost on me.

Woodworth had come to Chicago from Gouverneur, New York, a little town near the Canadian border not far from Lake Ontario. It was there in 1898 where he created a group called the Brothers of the Book. The group was dedicated to private printings “in dainty fashion (of) the literary gems he admires,” according to a brief story in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle for April 21, 1898. Woodworth held the title of Scrivener, a title we all recall from high school readings of Melville’s “Bartleby the Scrivener.” (Bartleby’s oft-repeated phrase, “I would prefer not to,” became my catch phrase after reading the story, annoying friends and family for months.)

(Allow me to digress a bit more: The archives of the Brothers of the Book are at the Newberry Library in Chicago and have not been processed so are not available online. As a result, I’m working from bits and pieces of information found elsewhere. I’ve also not been able to find out much about Woodworth. An obituary for him has been devilishly difficult to track down. If someone out there has some additional information about him, please let me know. Woodworth intrigues me.)

One of the few advertisements I could find for a book published by Laurence C. Woodworth. This ad comes from the May 4, 1919 New York Herald.

Woodworth moved from the tiny New York state hamlet of Gouverneur just after the turn of the century. As Starrett relates in his Tribune piece, “he was typographical expert for a firm of printers and was continuing his altruistic projects on the side.” Along the way he became known to booksellers and printers in Chicago during its Literary Renaissance. In a May 13, 1917 piece, longtime Tribune columnist Fanny Butcher gives us a few tidbits of information about Woodworth’s efforts.

The Brothers of the Book is a group of men and women—some 900 now, I think—who subscribe a small sum each year and who are privileged to buy, if they wish, the volumes which the brotherhood publishes. These volumes are always beautiful in their typography and are in limited editions. ‘About the only requirement for membership,’ I was told when I first ardently begged admission to the brotherhood, ‘is that the candidate must be a lover of the good, the bad, the true and the beautiful.’

The limitation page for Mon Ami Pierrot. The run of 550 copies was considerably more than the 200 or 300 Starrett recalled in his Chicago Tribune piece published more than 50 years later.

It's unclear who Butcher is quoting there, but she goes on to explain that if readers want to know more they should contact Woodworth, “who is Scrivener of the Brothers of the Book,” at his home, 504 Sherman Street, Chicago.

It’s no surprise that Starrett would be intrigued by a group called the Brothers of the Book. His description in the Tribune essay contains a quote about the group, explaining its membership would be limited to “Idealists, Poets, Dreamers, Bards, Artists, Artificers, Collectors, Players, Writers, and Craftsmen.”

Poet? Check.

Dreamer? Big check.

Collector and Writer? Big double check.

Brothers of the Book was clearly made for Vincent Starrett.

It’s no surprise to learn that Starrett himself was at one time a member of the group’s advisory board. Also on the board was famed Chicago bookseller Frank M. Morris along with well-known (and well-healed) bookmen from Boston, New York and Philadelphia. This was a crowd Starrett eagerly wanted to be associated with. When he wrote “The Unique Hamlet,” in 1920, these were the bookmen he wanted to impress.

Starrett believes the membership was limited to 200 or 300, considerably less than Butcher’s 900. Nonetheless, they both say that beautifully produced booklets were the group’s goal and that the print runs were limited. Starrett says Woodworth believed there were no more than 250 serious book collectors in the country, meaning people who would subscribe to the group and then purchase its little volumes.

Which brings us to the orange book.

Mon Ami Pierrot

The bright orange cover of the book. There was a bright orange box as well.

Published in 1917 in Chicago, Mon Ami Pierrot: Songs and Fantasies is a handsome example of the Brothers work under Woodworth and the man Starrett calls “his principal abettor and collaborator, Kenneth Banning.” Banning was a good poet “in his own field,” says Starrett, adding the backhanded notion that “his verse will be remembered, I suspect, more because it was published by Woodworth than on its own merit.”

Ouch.

Banning compiled the pieces for the tribute to Pierrot, the character based in Comédie-Italienne.

Paul Legrand as Pierrot, c. 1855. Photograph by Nadar.

According to Wikipedia: “His character in contemporary popular culture — in poetry, fiction, and the visual arts, as well as works for the stage, screen, and concert hall — is that of the sad clown, often pining for love of Columbine, who usually breaks his heart and leaves him for Harlequin. Performing unmasked, with a whitened face, he wears a loose white blouse with large buttons and wide white pantaloons. Sometimes he appears with a frilled collaret and a hat, usually with a close-fitting crown and wide round brim and, more rarely, with a conical shape like a dunce's cap.”

The character of Pierrot was in the air in late 1916 and early 1917.

A stage play, “Pierrot the Prodigal,” opened on Broadway in September of 1916 and ran for 165 performances—not bad for a play without dialogue. It must have felt more like a silent film, since music accompanied the performance.

The show came to Chicago in the spring of 1917 and prompted serious debate among critics, which kept the production in the news. Perhaps it was this excitement which prompted Woodworth and Banning to consider a book of poetry to the silent clown.

With Starrett’s role as a poet and member of the writing establishment in Chicago, it was natural that he would be approached to help fill out the volume. As he wrote decades later:

When I was asked if I had written any Pierrot poems, I was obliged to confess that I had not. Nevertheless, I wanted much to be in this unique book and I decided to translate two Pierrot poems from the French for inclusion. … The fact that I knew no French did not, at that early stage of my career, deter me.

Starrett didn’t know French, but he knew that Clarence Bradley, then head of the ChIcago Daily News copy desk, was proficient in the language. “It was from his literal translations that I contrived my rather stiff lines. Mon Ami Pierrot, I am happy to add, was a lovely book.”

Here are a few images from a recently obtained copy. You can judge the quality of the poetry for yourself.

Note: This is not Starrett’s copy. Nonetheless, I think it’s a lovely thing overall and deserves a place on the shelves, especially when it is paired with his Chicago Tribune feature.

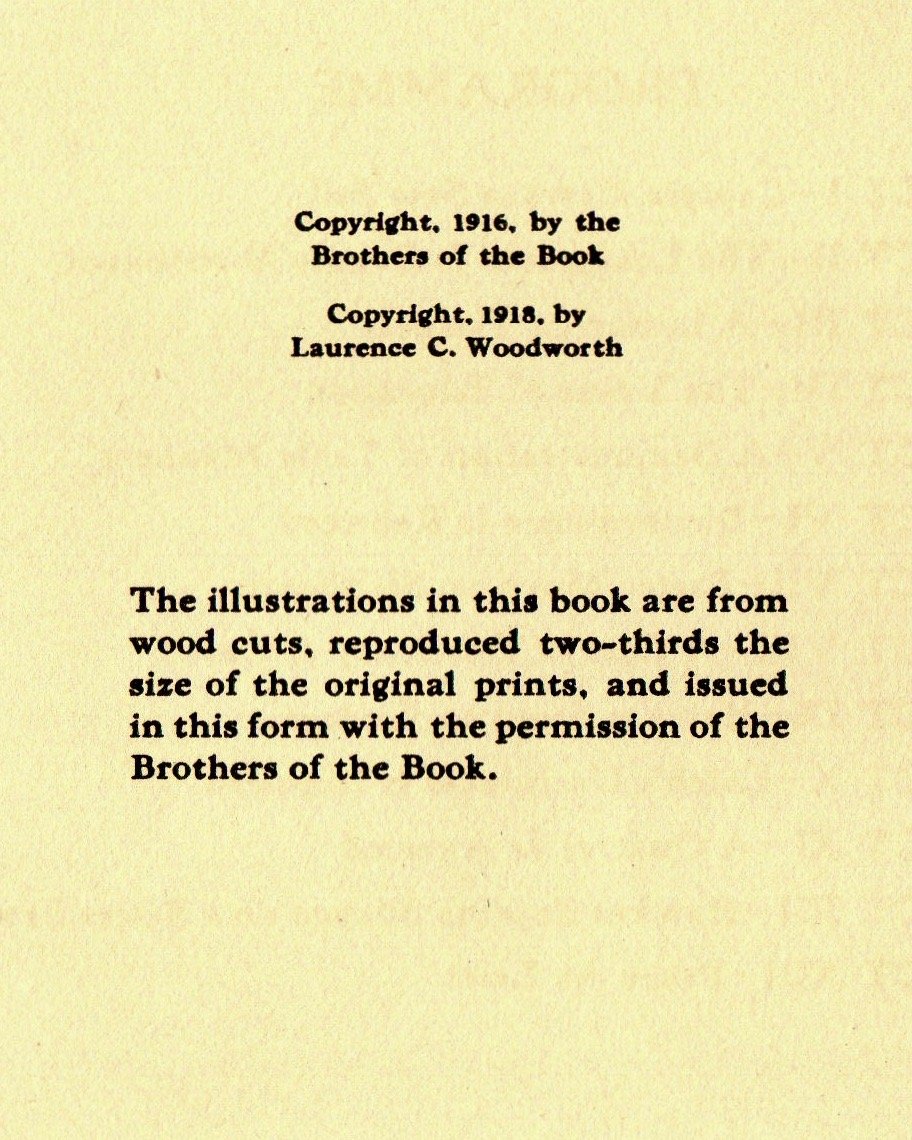

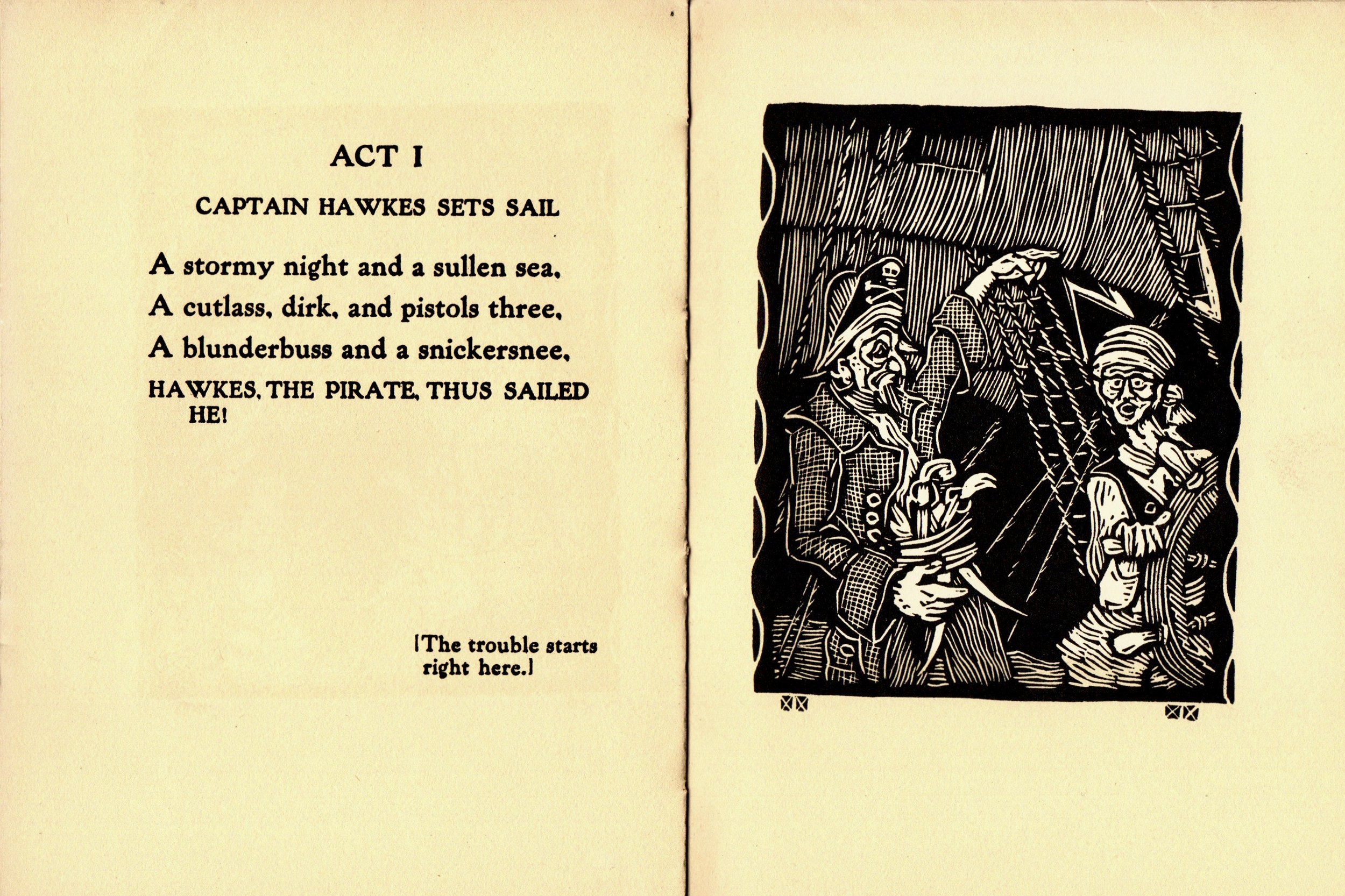

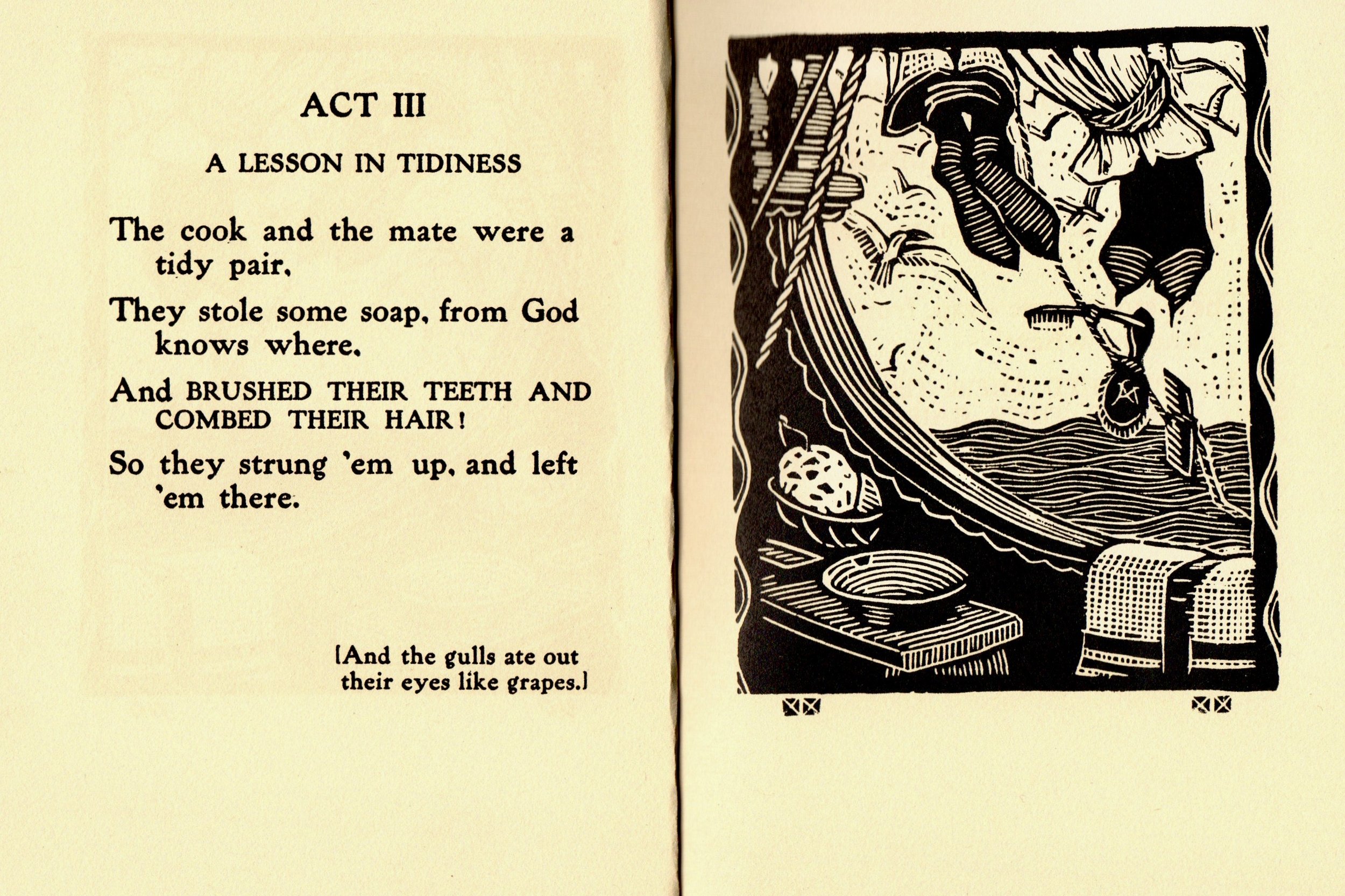

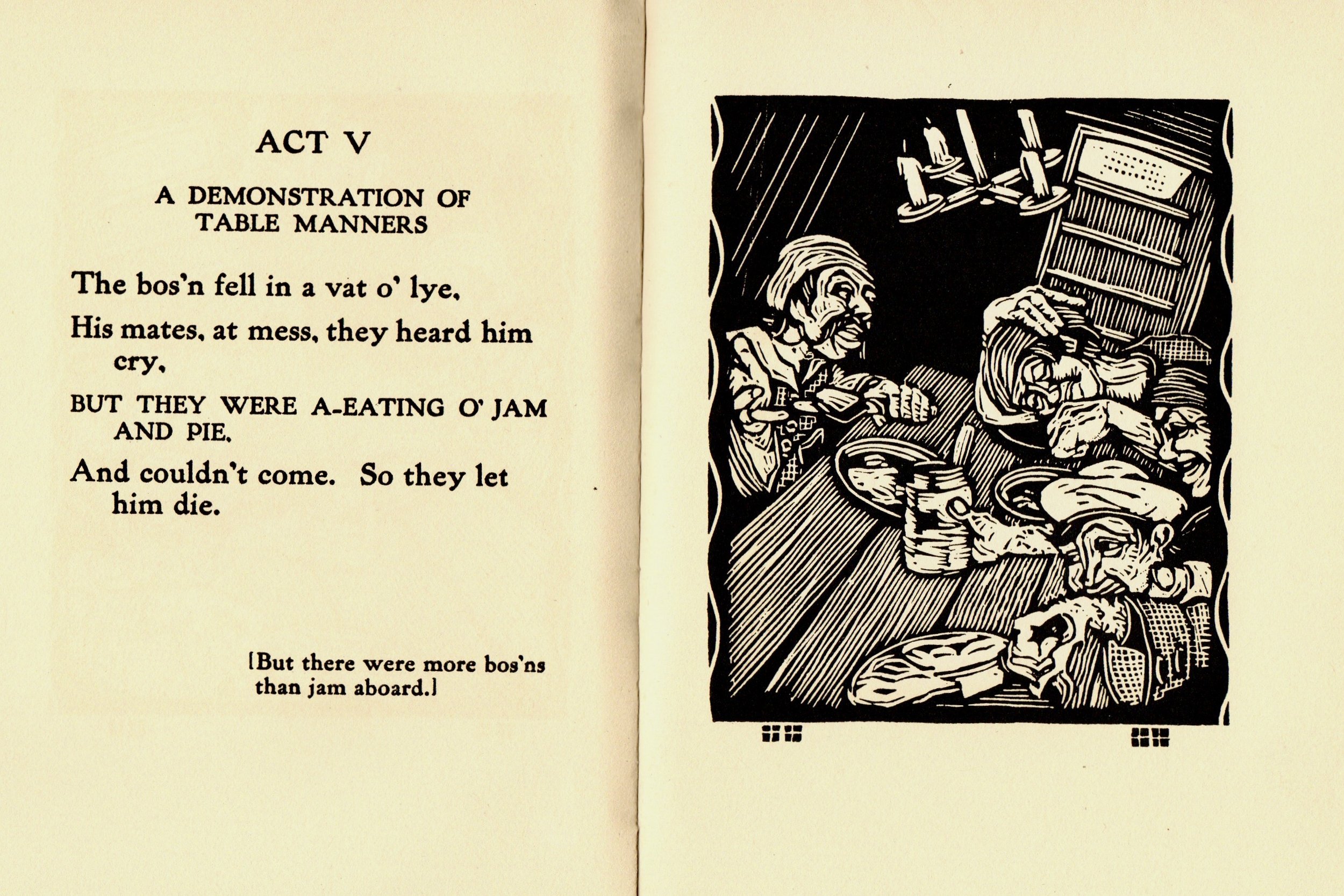

Pirates!

Speaking of Starrett’s feature essay in the Tribune, he had a few more thoughts about Woodworth and offered a serious compliment to the man’s memory and passion for books. It’s also clear that Starrett could relate to Woodworth in at least a few ways. (I should make clear that for most of his life, Starrett wouldn’t turn down a drink—especially if someone else picking up the tab—but he was not an alcoholic.)

Larry Woodworth was one of the most completely incurable bookmen I have ever known. Of course, he was often in financial difficulties, a circumstance that may or may not have contributed to his affection for Scotch. He died during the middle of Prohibition era when the country was flooded with what was then called “bad stuff.”

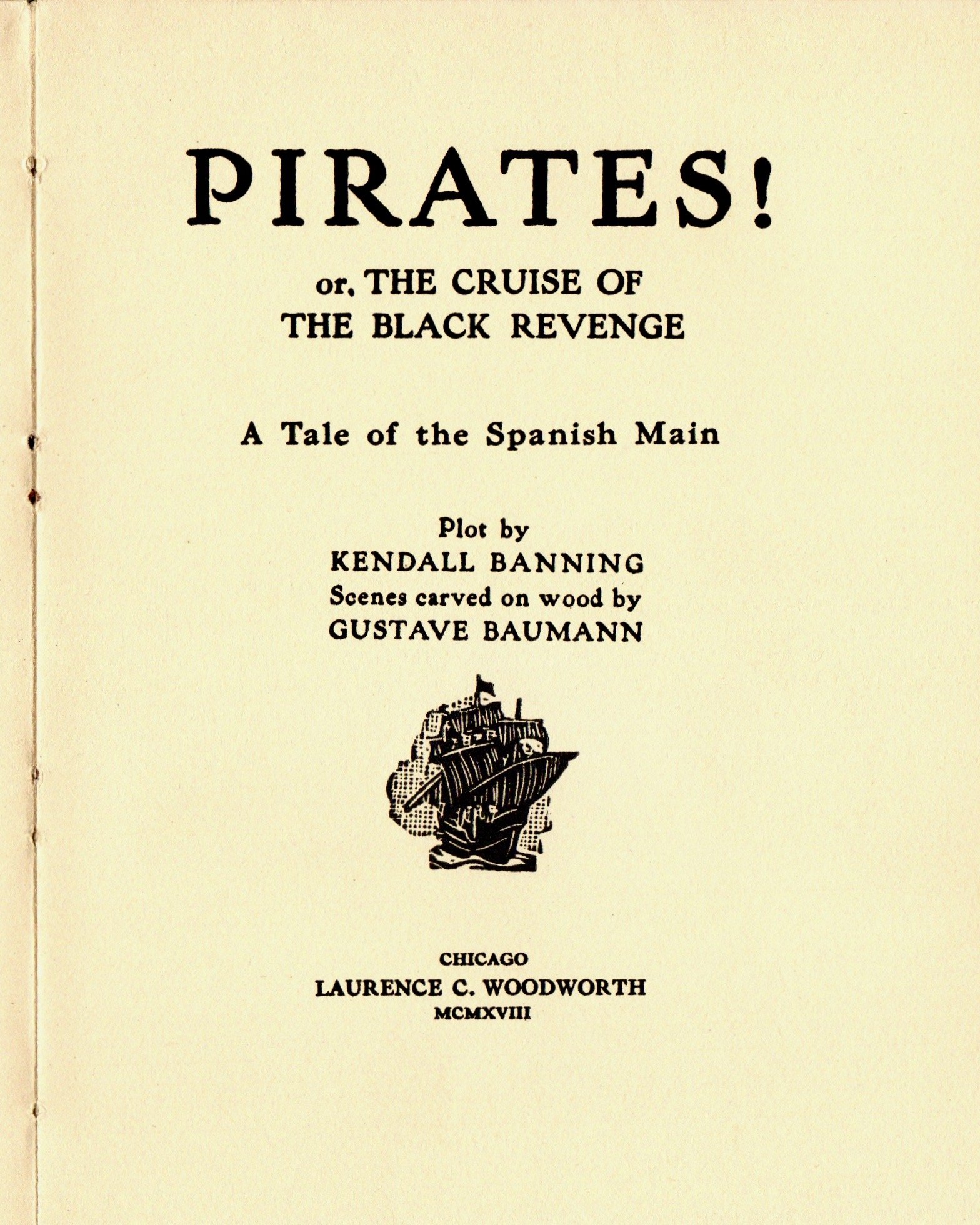

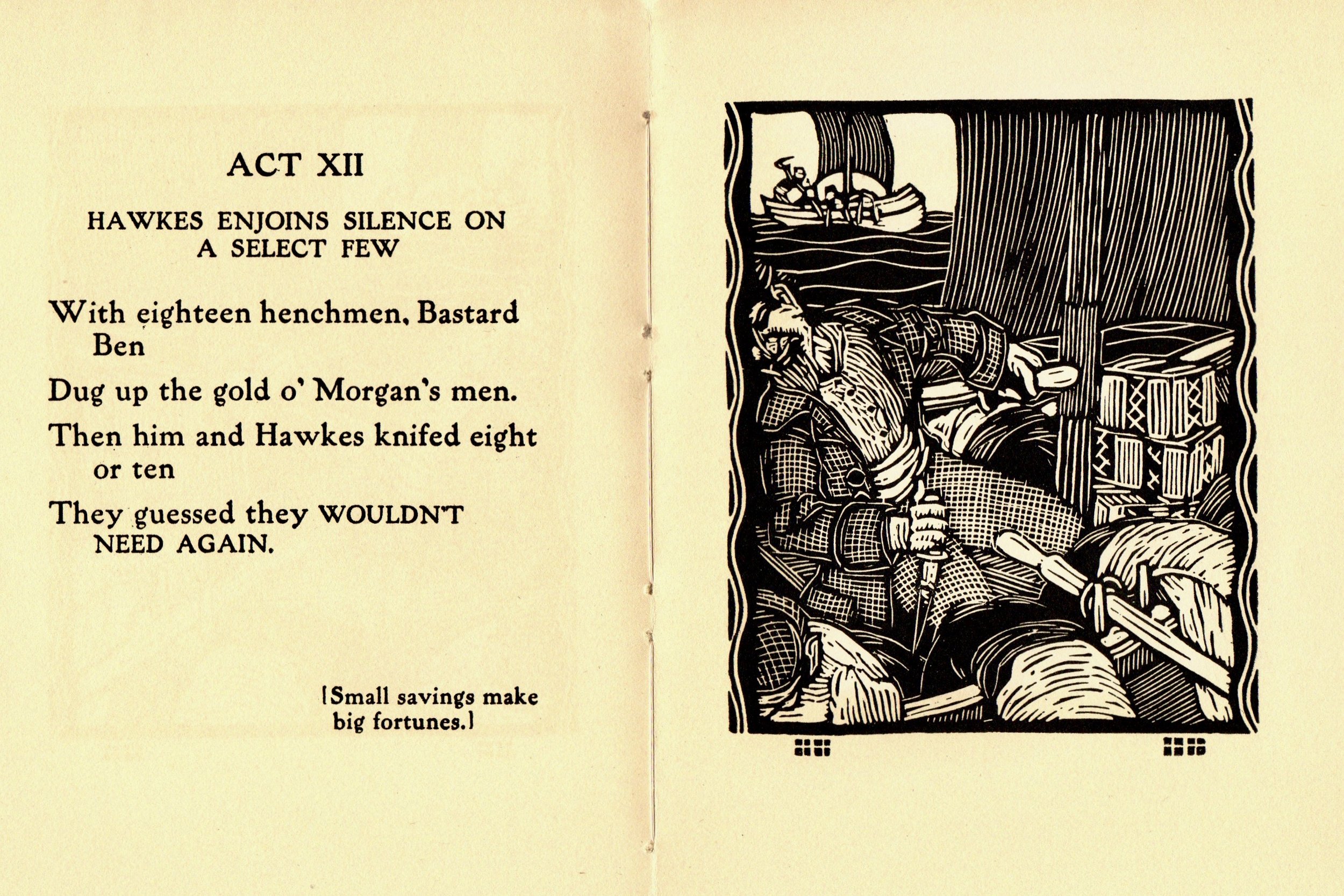

Starrett also recalls that Woodworth’s “most successful venture, as I recall it, was a volume entitled Pirates!, a ballad by Banning. One of Banning’s better pieces, it was admirably illustrated with the droll woodcuts of Gustav Bowman. It was later reprinted by popular demand in a smaller format and both editions are now prized by collectors.”

Naturally, Starrett used his pirate bookplate for his copy of Pirates!

The original Brothers of the Book edition was published in 1916 and then reprinted in 1918. I don’t know if Starrett had one of each, but I own Starrett’s copy of the 1918 printing.

The book must have been audacious for its time, with its gleefully bloodthirsty text. I have to say I am not a fan of the whole business, with each page delighting in different ways to murder the crew. That crew is made up of such unfortunately named characters like “Bunghole Bill” and the “Peg-legged Jew.”

This ain’t Treasure Island kids.

Here are a few of the less unsavory pages to give you a taste of the book.

A Final Thought

Fanny Butcher briefly mentioned Mon Ami Pierrot in her Chicago Tribune column for July 15, 1917.

Let us go back to that first image from the Tribune and you’ll note that the text was made up entirely of Don Quixote and Woodworth with Rathbone and Eliot—the true draw for most readers—showing up in the illustrations only. Those two will not be introduced into the story until the second jump. I am returning to this thought because I think I know where this essay started its life.

There were substantial cuts made in Starrett’s 1965 autobiography, Born in a Bookshop, before its publication. A hunt for those lost pages has been conducted by several folks, but the full manuscript has never turned up. I think this Chicago Tribune essay is part of what didn’t make it into the book. Woodworth is never mentioned in the published book. Starrett’s memoir mentions Eliot only in passing and Rathbone is not there at all, even in the chapter on the Baker Street Irregulars and Sherlockiana. It’s hard to believe he would write a biography and leave these three people out of his memoir.

The Tribune piece is written in the same “sauntering through the pages of my life” style as Bookshop. I suggest that this could be part of the missing manuscript. It would be just like Starrett to recycle this material. At 83 and in need of money to help pay medical and other bills, it would have been a good way of benefiting from his lost pages.

The entry for Mon Ami Pierrot in Charles Honce’s 1943 bibliography of Vincent Starrett’s work.