Alice—The Ageless Child

We are hurtling into the holiday season, when otherwise sensible and responsible people allow themselves the opportunity to share in a harmless bit of fantasy. For some, it’s the belief in Santa Claus. Others head to New York City to claim that a certain Baker Street detective is not fictional at all.

And at least one fellow wanted to have an adventure via Lewis Carroll’s Alice.

More than a century ago, Vincent Starrett paid tribute to the immortal spirit of childhood embodied in Alice, sometimes of Wonderland, occasionally through the Looking-Glass. Alice embodied the innocence of childhood for Starrett, who longed to experience once again the pure joy of adventure through the printed word. It’s time we follow him through one of his most playful expeditions. (Carroll, or rather Charles Dodgson, perhaps had a more complicated relationship with the real life model for Alice.)

We have leaped down rabbit holes frequently in these blog posts. But the expression was never so appropriate as we explore The Escape of Alice: A Christmas Fantasy.

Follow that white rabbit!

‘Our good fairy, Mr. Starrett’

Lucius Albertus Brewer, from a photograph published in The (Cedar Rapids) Gazette on March 13, 2022, p. 5.

Luther Albertus Brewer (1858-1933) was a publisher, businessman, philanthropist and civic leader in turn of the last century Cedar Rapids, Iowa. A staunch member of the Republican Party, his newspaper supported traditional Republican ideals.

He was also founder of the Torch Press, which started as an offshoot of the newspaper business and became a personal outlet for his own passions. Among those passions was the poetry of Leigh Hunt (1784-1859), the British poet who counted William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb among his inner circle. Brewer had one of the largest collections of Hunt’s work in the United States, which now resides at the University of Iowa.

It was probably the common admiration for Hunt and their shared passion for collecting that brought Brewer and Starrett into each other’s orbit in the early years of the 20th century. The two were also acquainted with each other through the Chicago-based literary group, The Bookfellows. Membership numbers were given out by the order in which you joined the Bookfellows. Starrett was No. 8; Brewer No. 14.

This friendship led to Starrett’s involvement in two Torch Press publications set for the holidays of 1919. One had the long title of A Little Book of Bookly Verse: Contributed by Several of the Bookfellows to Help Make Christmas Merry. It was published in an edition of 500 for the group’s membership.

The second Torch Press booklet involving Starrett was a gift to friends from Brewer and his wife, Elinore. The two had a tradition of printing little Christmas items in the previous several years.

They had missed sending out a holiday greeting in 1918, perhaps due to the start of The Great War. It was possible a second year would go by without a holiday booklet, but Vincent Starrett came along.

As Brewer says in his introduction:

It has been well said that a friend in need is a friend indeed.

Such a friend, Vincent Starrett, of Chicago, has proven to be to us.

Last year, more to our regret than to the regret of our friends, we were compelled reluctantly to forego the pleasure and privilege of holding a session with them around our fireplace or beneath our reading lamp.

And a similar situation was imminent at this Christmas time—when our good fairy, Mr. Starrett, one morning dropped on our desk The Escape of Alice with the cheerful message, “It is yours, Brewer, for your Christmas booklet, if you want it.”

So here it is—a pleasant Christmas fantasy—sent to our friends of old and to some new ones, with all the best greetings of the season.

Two hundred copies in soft brown wrappers were printed and distributed. Let us see what that “good fairy” Vincent Starrett produced to cheer folks through a difficult holiday season. You can read along by following this link.

The Escape of Alice: A Christmas Fantasy.

The tale begins as all good Starrett stories should: In an antiquarian bookshop.

Alice slips out of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, “leaving behind her a curious vacancy in one of the familiar pictures signed with Mr. Tenniel’s initials.” She nibbles a little cookie that makes her the size of a regular 13-year-old child and asks to buy her book from the kindly dealer, who tells her she has chosen wisely.

“Alice—the ageless child! It is one of the greatest compendiums of wit and sense in literature. There are only two books to match it. You shall have it for fifteen cents, for it is far from new, and I see what I had not noticed before, that the frontispiece is missing.”

“And what are the other two?” asked Alice, eagerly.

“When you are older you will read them,” said the old bookman. “They are called ‘Don Quixote’ and ‘The Pickwick Papers’.”

Suddenly Alice realizes she has no money and must give back her book. The dealer is aghast!

“Money!” cried the antiquarian. “Did I ask you money for this book? Forgive me! It is a habit I have fallen into for which I am very sorry. Money is the least important thing in the world. Only the worthless things are to be had for money. Those things which are beyond price—thank God!—are to be had for the asking. Take it, child! Tomorrow is Christmas day. I should be grieved indeed if there were no Alice for you on Christmas day—as grieved as if there were no Santa Claus.”

Gathering up her prize, Alice slips out into the cold Chicago Christmas Eve night. The world she encounters is every bit as bizarre to her as Wonderland, especially with the plethora of Santas who seem to sprout up at every corner. She recites a little holiday verse to help keep herself calm:

’Twas the night before Christmas,

And all through the house

Not a creature was stirring,

Not even a mouse....Well, that was not not surprising. Obviously, all the creatures who might otherwise have been stirring about the house on the night before Christmas were crowding and jostling each other in department stores, buying useless presents for people they didn’t like. Alice thought it odd that this hadn’t occurred to her before. It made the beginning of the poem quite clear.

Starrett’s inscribed this copy to his bibliographer, Charles Honce. As he did so often in later life, Starrett acts dismayed at his earlier work.

She eventually finds herself in the most unrealistic place in the city: A department store on Christmas Eve. There she meets a wise old Santa who appears less fake than the rest. He introduces her to one of his many assistants, a man made completely out of wood.

Everything was wood, and Alice was holding on to his wooden fingers, and he was talking out of his wooden mouth, and the whole affair was the most wooden episode Alice could remember.

He soon starts spouting Wonderland-style nonsense verse:

O, ferocious and atrocious is the beast they call the lynx;

And fierce his howl, and black his scowl, and red his jowl, methinks....

Alice offers in reply:

I thought I heard a parson swear

Because his eyes were sore;

I turned around, and saw it was

The watchdog’s honest snore.

“Alas,” he whispered, tearfully,

“That two times two is four!”I thought I saw a mastodon

Upon the pantry shelf;

I looked again, and saw it was

A picture of myself.

“O dear,” I said, “the albatross

Is eating all the pelf!”

There are references to J.M. Barrie, H.G. Wells and American poet Amy Lowell. Each gets a sardonic snipe or two, as when Alice and the wooden man fight over who wrote more introductions, Barrie or Wells. After a while, Alice grows weary and heads back to the book dealer.

The precious volume, which once she had thought a prison, was safe beneath her arm. Well, she knew now what she would do. She would give it back, and if the old man were so kind as to let her, she would creep back into the pages, and be happy there again forever....

“Poor child,” smiled the old bookman, when she had related her adventures, and cried over them. “… To the child of thirteen, all things are real if they are beautiful, and all things are unreal which are ugly. Anything is real that we want to be real. Sensible writers, like Barrie, learn this at thirteen and tear off all the remaining years of the calendar. Time passes, but they remain thirteen; they improve their style, their appreciation of beautiful things deepens, their outlook is broader and finer, but at heart they are still children. They have never escaped from their thirteenth year, and they never will—and they are very glad about it.”

Alice nibbles a cookie that shrinks her down and she slips back to where she belongs, as the dealer flips through the pages.

Suddenly the book fell from his hand, and clattered onto the floor, striking his foot as it fell. At the same instant, of course, he awoke, sitting in his chair near the old stove. He smiled a little, but was not surprised, for he was used to dreaming strange and pleasant dreams. As he stooped to pick up the book, a customer entered the store.

“What have you there?” asked the stranger, looking at the book in the old man’s hand. “Alice in Wonderland? Charming thing! What do you ask for it?”

“Not this copy,” said the old man, firmly. “This is my personal copy. This is one book you cannot buy.”

The Annotated Alice

Maxwelton braes. Or brays.

There are several allusions here that contemporary readers would have understood and I needed to hunt down. For example, at one point, Alice and the wooden man meet up with the Plausible Donkey, who claims a notable bloodline.

“The fact is, I am descended from that notable singer, Maxwelton.”

“Maxwelton!” echoed Alice, in surprise. “I thought that was a song.”

“It was originally,” the Plausible Donkey said plausibly. “My ancestor was named after the song because his brays were bonnie.”

Maxwelton’s brays is a play on Maxwelton Braes, a song that is better known as “Annie Laurie '' and would have been familiar to Starrett from his Scottish/Irish family history. The verse is attributed to a poem by one William Douglas. It begins with

Maxwelton's braes are bonnie,

Where early fa's the dew,

Twas there that Annie Laurie

Gave me her promise true.

Daisy Ashford, H.G Wells, J.M. Barie and Mr. Britling

Alice asks the wooden man for a 1919 book written by a nine-year-old titled The Young Visiters by Daisy Ashford. Ashford was indeed nine when she wrote the book, which was popular in England and briefly in the US.

(Fun note: A play adaptation of Ashford’s book had a short New York run and was reviewed by none other than Alexander Woollcott on November 30, 1920 in The New York Times. In 1934, Woollcott and Starrett would ride in a hansom cab together to the first official dinner of the Baker Street Irregulars.)

Alice points out that J.M. Barrie wrote an introduction to Miss Ashford’s book, and the wooden man claims “Then Barrie wrote it! That ends that!”

“It doesn’t end anything,” cried Alice, almost in tears. “And he doesn’t write as many introductions as H. G. Wells, anyway!”

“O-ho!” said the wooden man. “Well?”

“Wells!” said Alice, sharply. “Wells, Wells! How many wells make a river?”

“Really,” admonished the wooden man, “you mustn’t get out of temper. I don’t like Wells any more than you do. I find it difficult to get to the bottom of them....” He fell to singing:Mr. Britling saw it through,

That was more than I could do!

Central, ring up Heaven’s bells—

Get me God, for H. G. Wells.

Image from Wikipedia

Mr. Britling Sees it Through was a war-time novel written by H.G. Wells and published in September 1916.

Highly popular during and immediately after the Great War, it has since fallen into obscurity.

There is also a rather cruel joke about the weight of Amy Lowell’s weight.

I won’t repeat it here.

One last point: Alice is 13 in Starrett’s tale, but is 7 or so in the original. The point is not a small one. The wooden man reports that he was never that age. “When my thirteenth birthday approached, I tore off an entire year of the calendar, and passed right into my fourteenth year.”

The wooden man is later rude and clearly lacks the ability to be playful like a child. Alice reasons that “It is very evident that he tore off his thirteenth year. That is the year when people learn to be polite. And he said I was not real! I never knew till I was thirteen how real I was.”

The elderly bookseller agrees: “Indeed he did need his thirteenth year. That is the age at which one best appreciates what reality is. Once learned, it is a lesson never to be forgotten.” He then goes on to explain that it is only those adults who can reach back and get in touch with their 13-year-old selves who can appreciate the distinction between fantasy and reality. He is clearly speaking for the author when he says:

“At heart they are still children. They have never escaped from their thirteenth year, and they never will—and they are very glad about it.”

The Ageless Alice

A promotional brochure for Wagenknecht’s 1948 book, A Fireside Book of Yuletide Tales.

Starrett’s story about Alice was first published in 1919, but it has experienced a long life.

Edward Wagenknecht, who taught literature at the University of Chicago for many years, included it in his anthology, A Fireside Book of Yuletide Tales. Published by Bobbs-Merrill Company in 1948, it was his second such holiday-based anthology, coming three years after A Fireside Book of Christmas Stories.

“The Escape of Alice” is in good company, and has a spot in the book just before O. Henry’s famous “The Gift of the Magi.”

Starrett made a few revisions on the tale for this publication, taking away some of the dated references, but kept the Lewis Carroll penchant for word play.

The story went on to be published in newspapers in 1956. Once again, Starrett made some updates and edits, but the general tale holds together much as it did when the Brewers published it 37 years before. “The Escape of Alice” ran in holiday newspaper editions fattened by Christmas advertising.

A portion of the 1956 newspaper version of “The Escape of Alice,” as it was published in The Daily Iberian in New Iberia, Louisiana, on Saturday, December 22, 1956, page 9.

I’ve found that the tale was published in The North Bay (Ontario) Nugget, The York (Pa) Daily Record and two Louisiana newspapers, The Daily Iberian in New Iberia and The Baton Rouge News Leader. I’m sure there are others.

Dayna (McCausland) Lozinski gave the tale new life when she wrote a brief. insightful and appreciative introduction about it for a 1997 reprint.

As she points out, Starrett substituted a department store’s Toyland for Carroll’s Wonderland. Both have their own sense of unreality.

She also identifies the two verses from Alice cited above (“I thought I heard a parson swear”) as part of “The Mad Gardener's Song” from Carroll’s later work, Sylvie and Bruno, published in 1889. The book is not well known today, but Starrett knew it well enough to parody the poetry.

Dayna’s bright blue booklet was published by The Silicon Dispatch Box Press. The same publisher used “Alice” as the title piece in the anthology The Escape of Alice And Other Fantasies, edited by Peter Ruber and published in 1995.

Personal Note: I need to thank Dayna for her help, guidance and kindness in putting this essay together. She and I have been writing back and forth about Starrett and Alice for quite some time. I hope this humble blog post pleases her.

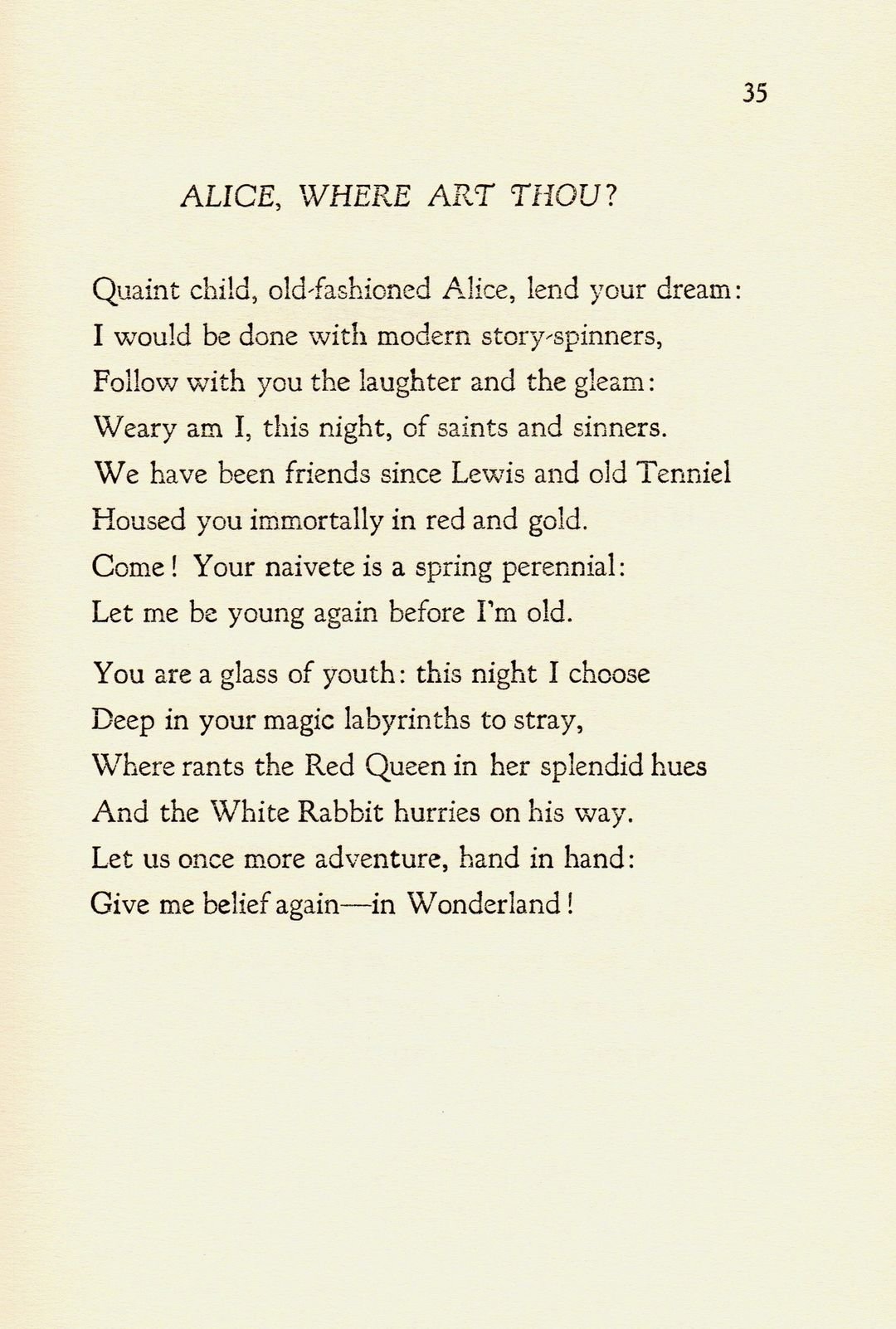

‘Alice Where Art Thou?’

Starrett would come back to Lewis Carol and The Ageless Child again for his final anthology of poetry, Brillig, published in 1949 when Starrett was 63. The book takes its name from a poem recited by Humpty Dumpty to refer to the afternoon, when the day was done and evening was coming on.

It was a fitting allusion.

Starrett was in the afternoon of his life, and while the book’s title was playful, the verses themselves held more than a few meditations on aging and death.

Even among these sad meditations, however, he could still hope for solace in his childhood friend and her madcap adventures. In “Alice, Where Art Thou?” Starrett invokes the ever young Alice, begging with her to “Let me be young again before I am old.” At the end he pleads,

Let us once more adventure, hand in hand:

Give me belief again—in Wonderland!

As he aged, I like to think that Starrett took some comfort from the fact that Alice, like Sherlock Holmes, was always there waiting for him. As they are always here for us too.

Compliments of the Season.