VS & TS

The Bookman and the Poet

Vincent Starrett briefly discussed his visit with T.S. Eliot in this extended feature story for the August 10, 1969 Sunday Chicago Tribune. Note how the Tribune’s art staff took a photo of Eliot and substituted his face for Basil Rathbone’s.

“The Yellow Fog”

I was recently honored to give a Zoom talk for the Baker Street Irregulars Trust about Vincent Starrett’s beloved sonnet “221B.” (I’ll share the link when it is posted should you like to hear it.) During the talk, a few folks asked if it was possible that Starrett was influenced by T.S. Eliot’s “Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

If I recall correctly (I failed to capture the comments, so apologies for not being able to credit those who asked) folks suggested that the references in “Prufrock” to “The yellow fog that rubs its back upon the window-panes” might be echoed in Starrett’s “A yellow fog swirls past the window-pane/As night descends upon this fabled street.”

It’s an intriguing idea. Certainly Starrett picked up bits and pieces of ideas from many places. So far as I know, he did not acknowledge a link between the two, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t unconsciously borrow the concept.

There are definite links between Eliot and Starrett. While they were different in many ways, the two shared a passion for poetry and Sherlock Holmes.

“The Love Song…”

Starrett would have been well aware of Eliot and “Prufrock,” as was much of the literate world in 1915 when Poetry: A magazine of verse published the controversial work. Those of us who grew up reading “Prufrock” in high school might lack an appreciation for how celebrated and debated the poem was at the time of publication.

The cover of the June 1915 issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, which featured T.S. Eliot’s groundbreaking “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

Eliot broke with the romantic traditions of the past, opting for a stream of consciousness style that shattered long-held rules of meter and rhyme. It seems remarkable today, but Eliot’s fever dream of a poem shocked many and was denounced by some. (Imagine if a rapper had walked into a salon where Elizabeth Barrett Browning was counting the ways of love.) His work sparked debates in newspapers and magazines and the hubbub only grew louder when he published “The Waste Land” in 1922.

I’ve not been able to find Starrett’s specific thoughts about these two influential poems, but we can make some educated guesses about this reaction. As someone who admired the romantic poets of his youth, it’s natural to assume that he would have found Eliot’s work hard to swallow. But the fact is that Starrett was a broad-minded reader and able to appreciate the works of those who sought to used poetry to reflect the reality of life, rather than romanticize it.

As he matured, Starrett rejected much of his earlier poetry in favor of verses that no longer romanticized his life in a dreamlike style. Above all, he loved seeing passionate discussions of art among his friends and in the media and often defended those whose creativity brought calls for censure.

We can conclude that Starrett would have been aware of Eliot’s role in making poetry a new and forceful expression to the contemporary life of the early 1900s. He might not have liked it, but he would have defended Eliot’s right to write it.

“Every writer owes something to Holmes.”

The listing for Eliot’s review of The Complete Sherlock Holmes Long Stories from page 207 of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, first edition.

For his part, Eliot was–like Starrett–an avowed fan of mystery novels in general and Sherlock Holmes in particular. Unlike many fellow early 20th century writers who turned their noses up at the mere mention of detective stories, Eliot was a public advocate for the form and its most famous creation. Indeed, in a review of The Complete Sherlock Holmes Short Stories for The Criterion magazine, Eliot goes so far as to observe that “Every writer owes something to Holmes.”

Priscilla Preston commented on this in her article “A Note on T. S. Eliot and Sherlock Holmes” in The Modern Language Review for July 1959. She writes, “Although Mr. Eliot was referring to writers of detective fiction, the remark was prophetic; he himself was to owe something to Holmes, or more precisely, to the crealtor of Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.”*

Starrett was certainly aware of Eliot’s review. He included Eliot’s essay in his checklist of important Sherlock Holmes commentaries and critiques in the appendix of the 1933 edition of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Starrett called it “an important review,” but said its exact date is “uncertain,” perhaps because he didn’t own the journal and had only read about Eliot’s review.

Musgrave, Murder and Macavity

As many commentators (including Chris Redmond) have pointed out, Eliot wrote references to the Holmes stories into several of his works, most famously:

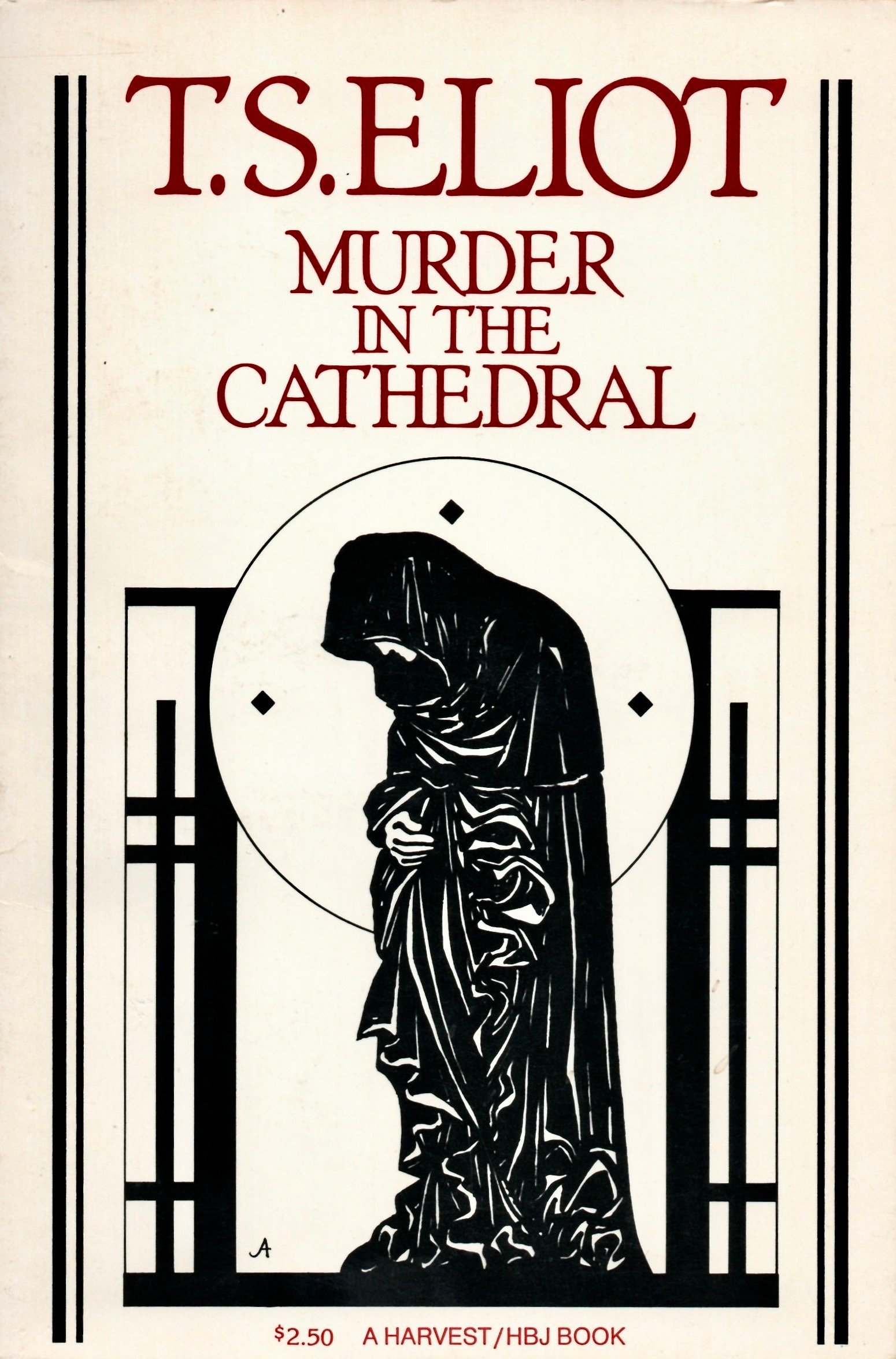

Slipping elements of The Musgrave Ritual into the dialogue of his 1935 verse play, Murder in the Cathedral. (For those not familiar with this passage, see page 28 in this pdf.)

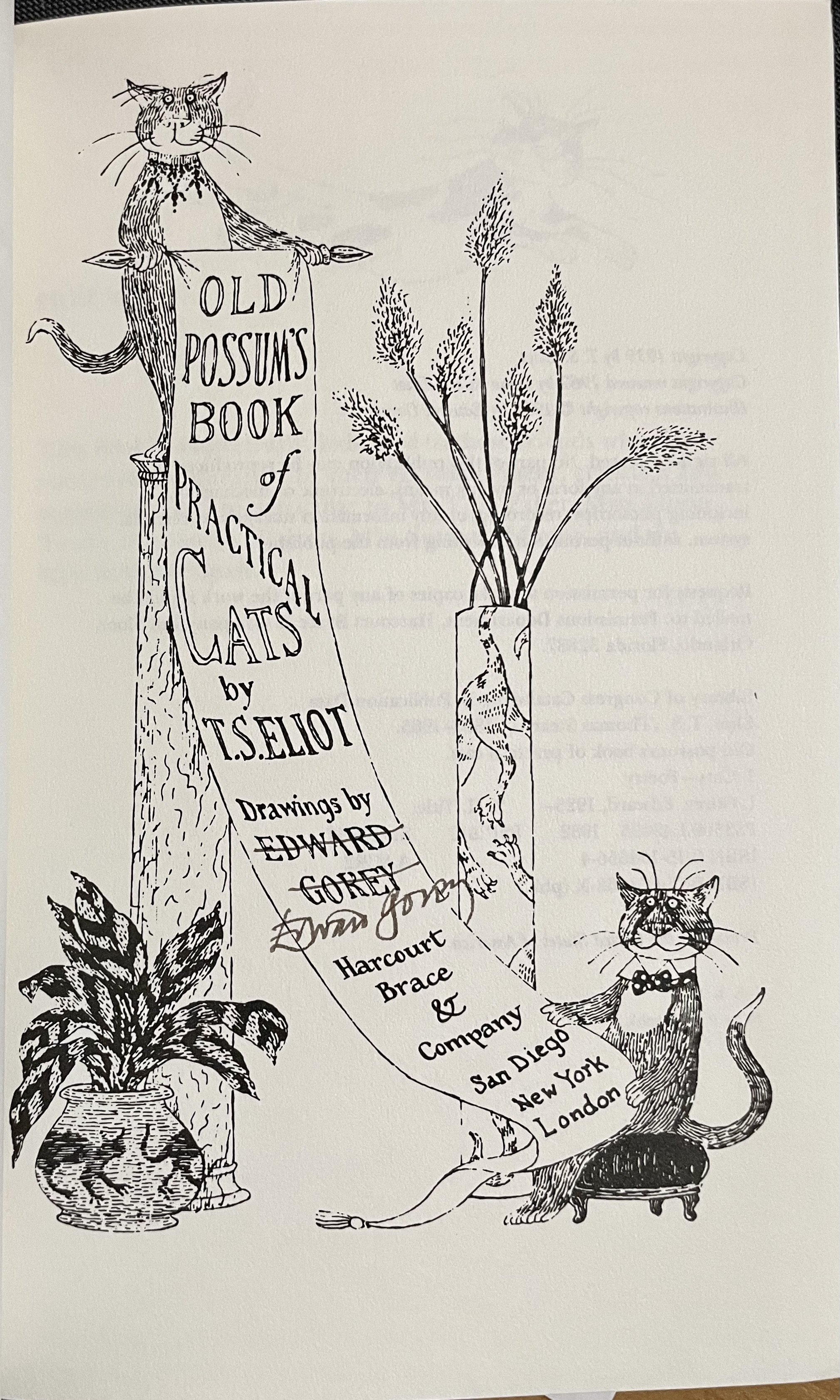

Turning Prof. Moriarty into a devilish feline in the Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats. “Macavity: The Mystery Cat” was a favorite of Eliot’s readers.

When the musical Cats came along in 1981, the story of the sneaking feline was one of the most popular of the show’s numbers, at least for Sherlockians.

“He resembled Sherlock Holmes”

Starrett and Eliot met briefly in the spring of 1956. (I would have loved to been there for that interview.) They were about the same age and the two men would have had a natural bond through their love of Sherlock Holmes. The poet was in Chicago for four days as part of a U.S. tour. Starrett was first struck by Eliot’s appearance. As he briefly recounts in his memoir Born in a Bookshop, Starrett felt Eliot could have gone on the stage as the great detective.

“My first glance at T.S. Eliot … came as a shock, although a pleasant one. He resembled Sherlock Holmes in precisely the way of those incomparable Sherlocks of stage and radio, William Gillette and Basil Rathbone. Tall, dark, distinguished – and lean – he looked the part.”

His “Books Alive” column for May 20, 1956, was even more pointed.

“Some enterprising producer ought to think about starring T.S. Eliot as Sherlock Holmes. He has the right stature and leanness, and he would look the part admirably in a Sherlockian dressing gown, while arguing a knotty problem in the upper regions of epistemology. Not the mouse-colored dressing gown, however; there is nothing of the mouse in the world's most controversial poet and critic—although a natural modesty and courtesy might mislead a rash questioner. I was sorry he didn’t smoke a pipe.”

Starrett added that Eliot was like, “a more bookish Holmes, in spectacles and with a cigarette,” as “he sipped sherry and discussed detective stories with the authority of an addict.”

“I am, dear sir, canonically yours,”

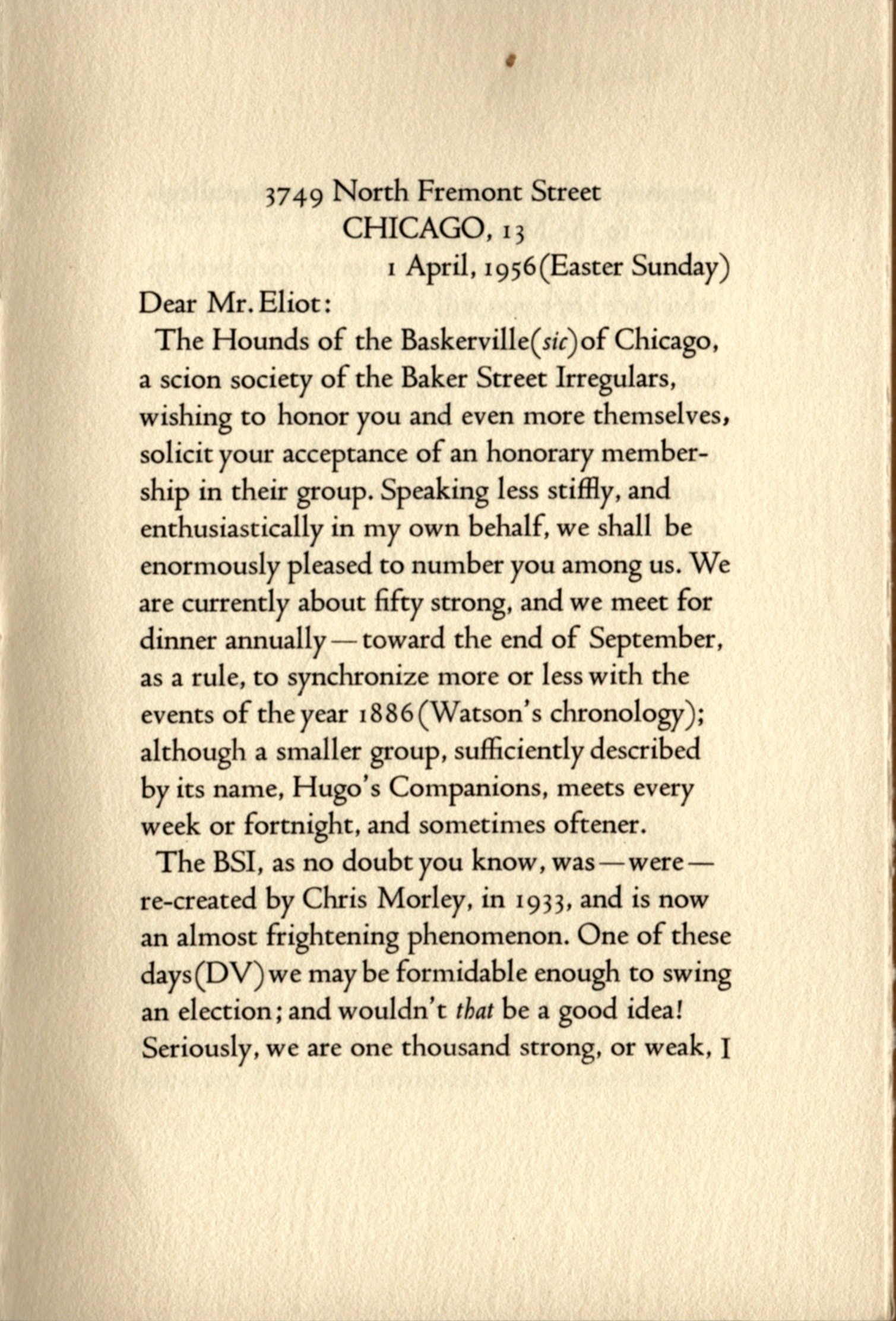

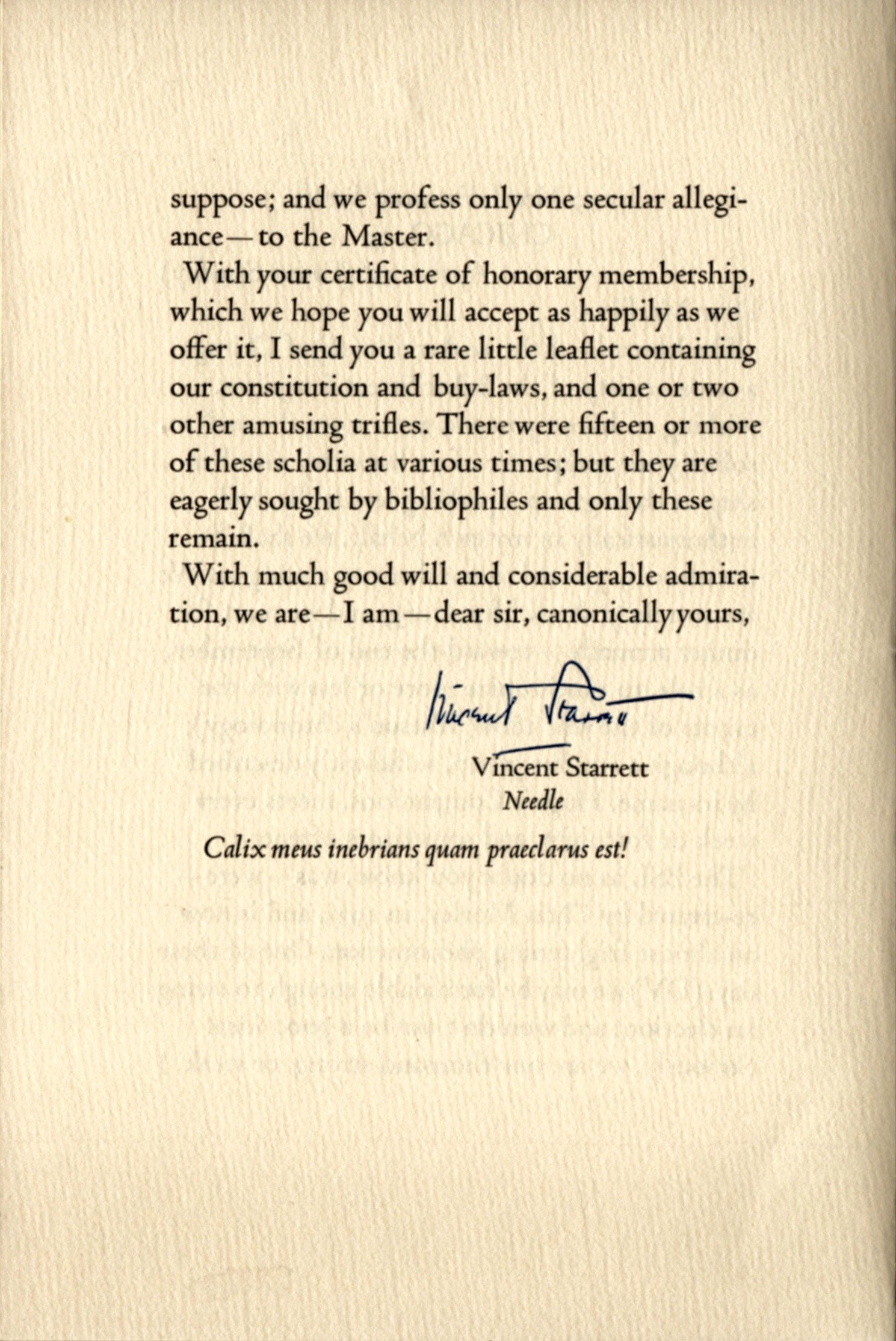

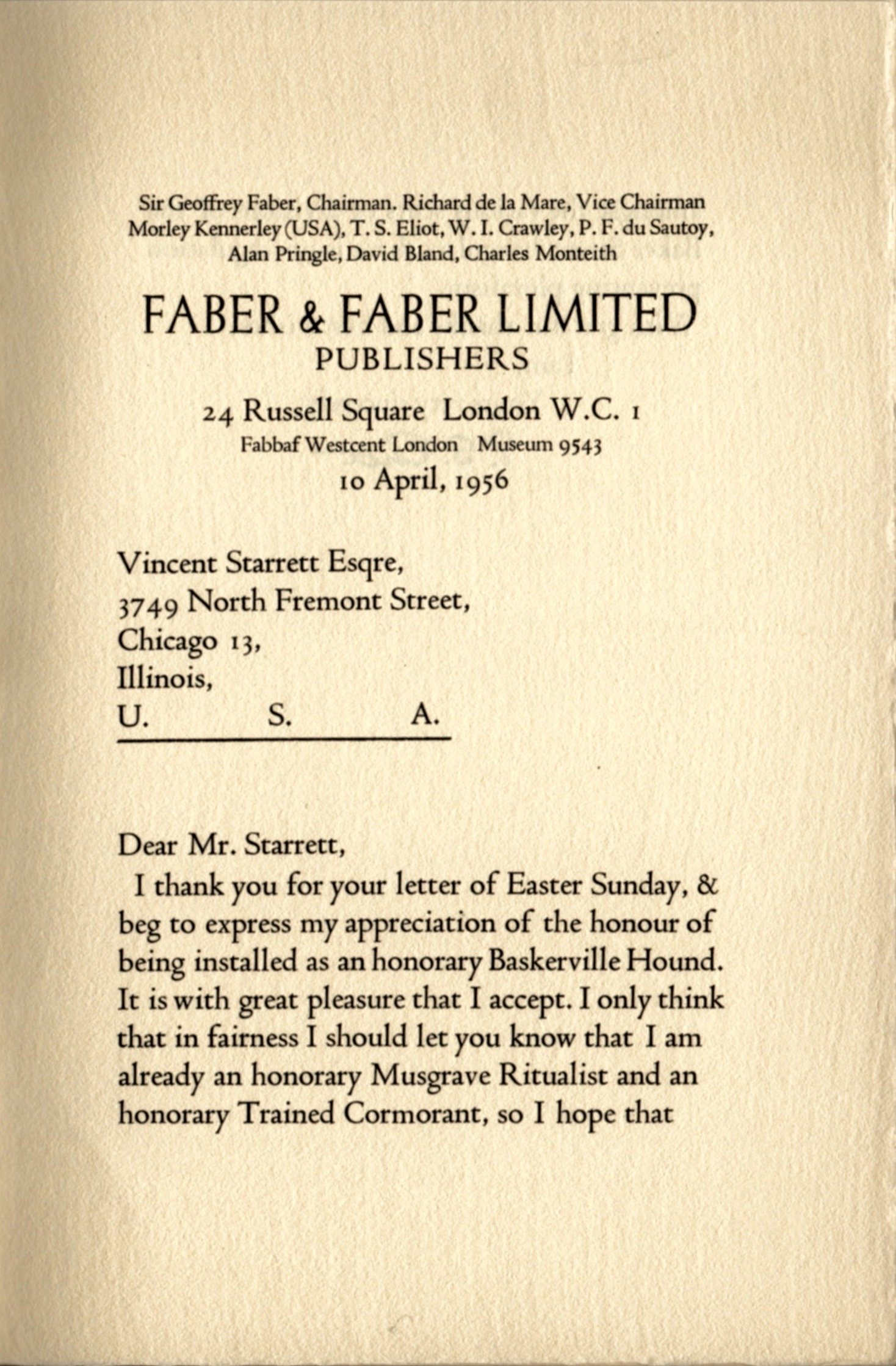

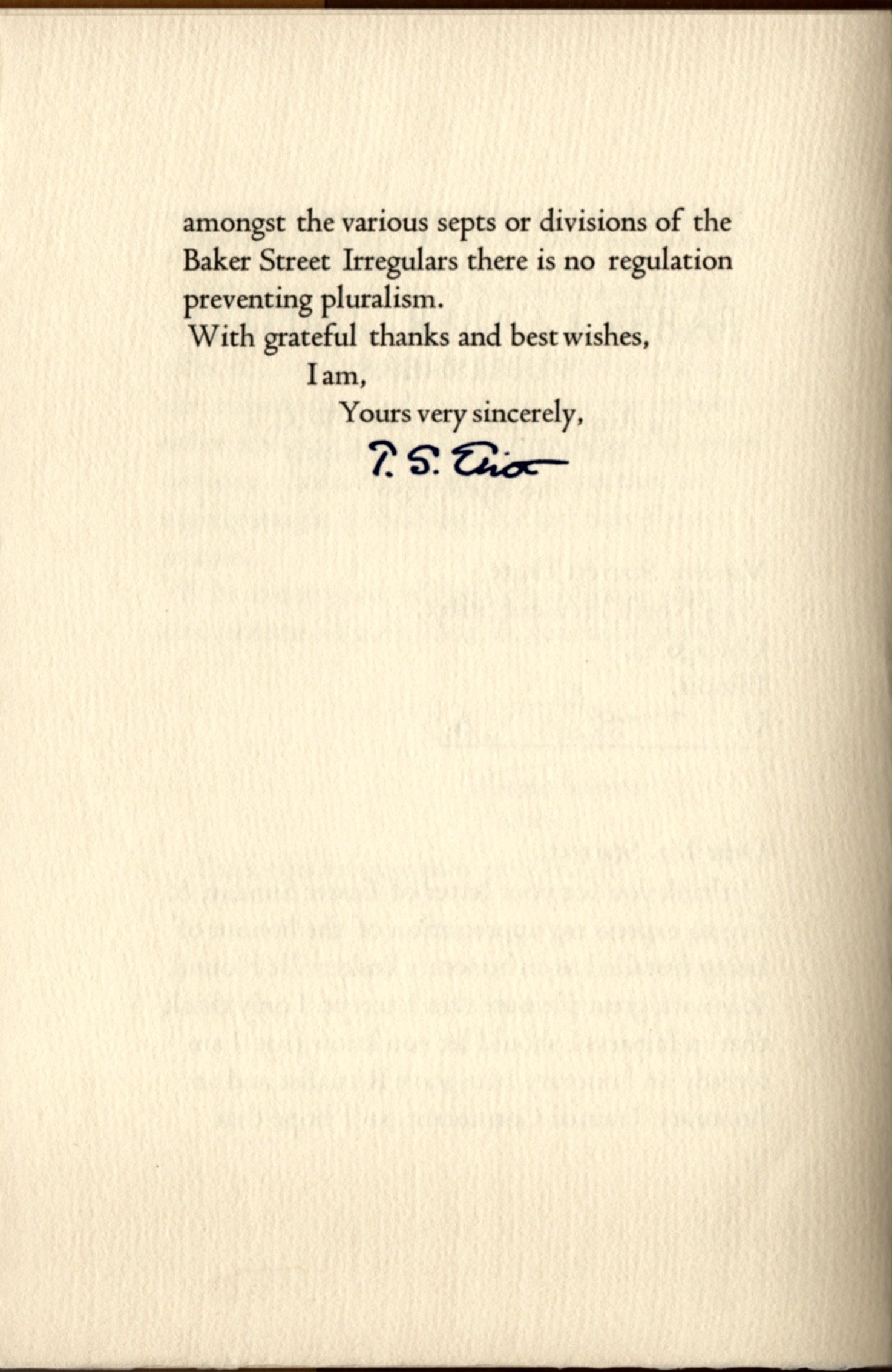

A few weeks later, Starrett sent a letter offering Eliot membership in the Hounds of the Baskerville (sic). As you can see, Starrett mentioned that irregular devotion to Holmes had grown so large that it could one day swing a presidential election! Eliot accepted, but noted that he was “already an honorary Musgrave Ritualist and an honorary Trained Cormorant.”

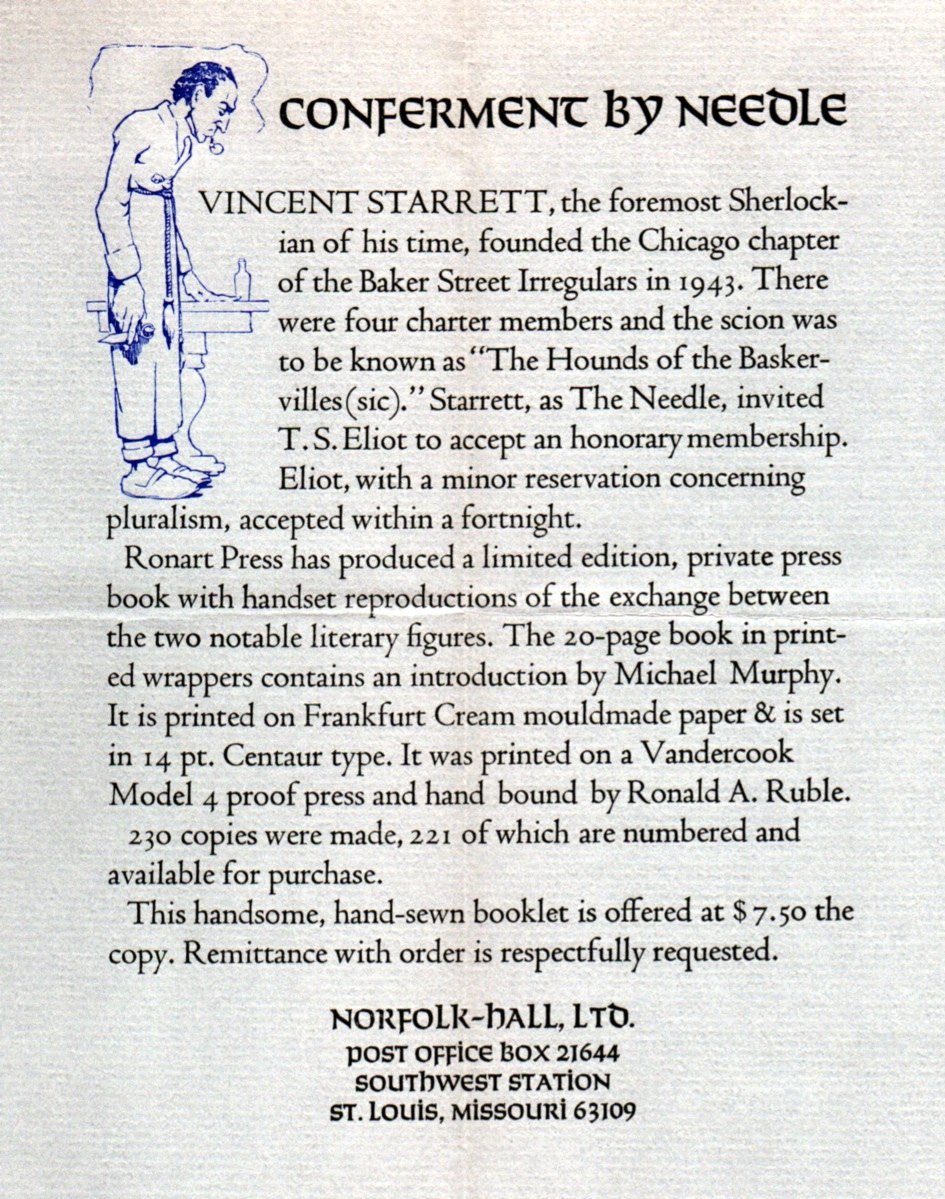

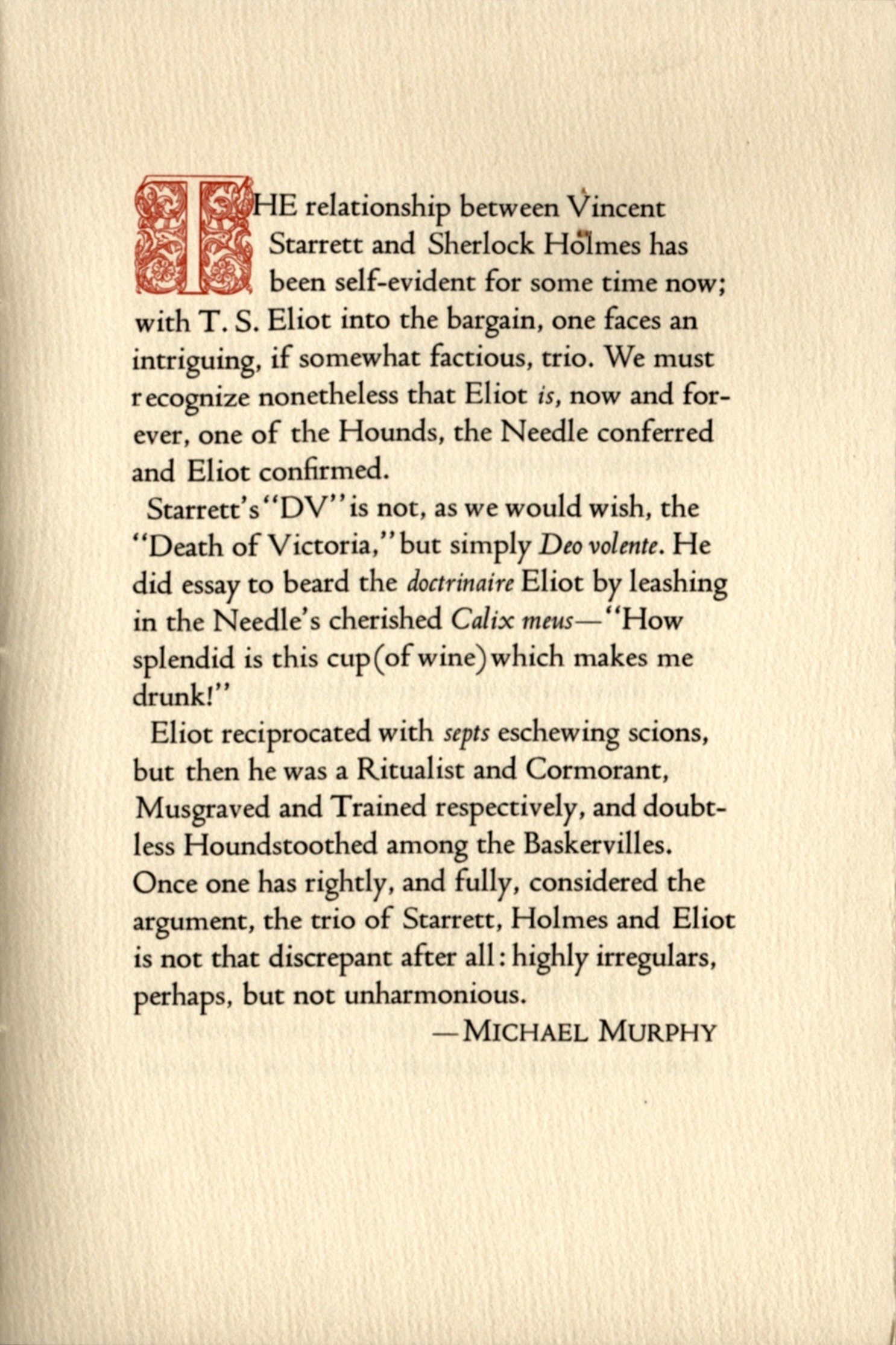

Their brief correspondence was published after Starrett’s death in June 1980 via a little booklet edited by Michael Murphy. The title references Starrett’s role as “The Needle” of the Hounds. We’ve discussed the booklet’s cover image elsewhere in these pages.

So it’s clear that Starrett and Eliot had at least a brief but decidedly Sherlockian set of interactions. Did Eliot influence Starrett’s most famous sonnet? It’s hard to say at this far remove.

But it is pleasant to think that the creator of Macavity played a role in the creation of the Sherlockian world’s most beloved sonnet.

An advertisement for Conferment by Needle, a 1980 booklet by Michael Murphy about the Sherlockian relationship between Starrett and T.S. Eliot.

*Priscilla Preston. “A Note on T. S. Eliot and Sherlock Holmes.” The Modern Language Review 54, no. 3 (1959): 397–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/3720909.