'I know him from the photograph.' – The Man with the Twisted Lip

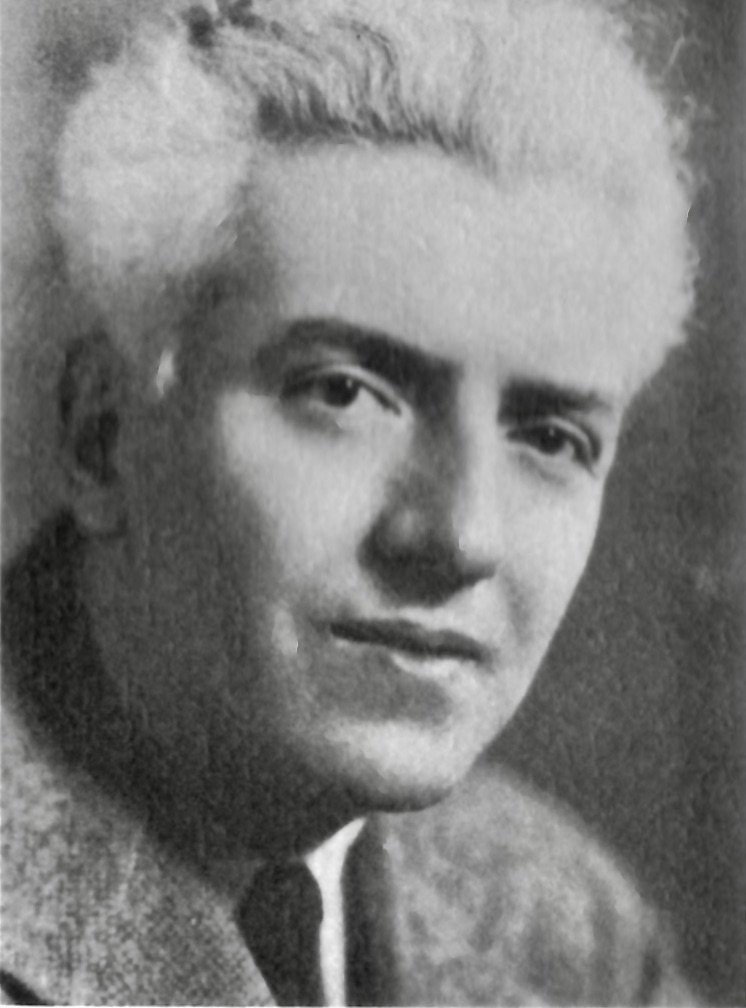

Ben Hecht once called Viincent Starrett “the tallest and handsomest reporter” at the Chicago Daily News and to Burton Rascoe, he was the “most distinguished looking figure in American letters.” Starrett was aware of good looks. He held the same opinion about his distinctive visage that Holmes held about his detective abilities: “He was as sensitive to flattery on the score of his art as any girl could be of her beauty.”

I thought it would be fun to see how Starrett changed over the many decades of his life.

Little Charlie Starrett

This is the earliest known photograph of Starrett that I’ve been able to find. Members of the Starrett family gifted me an album of photographs several years ago. I thanked them then and do so again. You’ll be seeing more from the album as we move along.

The picture is undated, but I’m guessing he is three or four. This photo would have been taken shortly before his parents moved the family from Toronto to Chicago.

Don’t you love the Little Lord Fauntleroy outfit? His hair is a bit unruly, but dark and full. We’ll be tracking that as we move along.

He was known as Charlie in those days, and his family would call him Charlie for the rest of their lives. The original photo has three children in it, as you can see below. That’s Charlie on the right, his brother Stanley in the middle and little Hugh Young on the left with the kewpie doll hair. Hugh was a cousin on his mother’s side of the family.

From left: Hugh Young (cousin), Stanley Starrett (younger brother), Charles Vincent Emerson Starrett (Charlie)

Charlie as a teen

A 1901 family photo.

Once again, I’m indebted to Starrett’s family for this image, tiny though it is. It was taken in 1901 and shows Charlie when he was 15 years old. He looks handsome in his suit standing in the back center of the photograph. His hair is perfectly groomed.

Starting on the left, you see his mother, Margaret Deniston Young Starrett, holding the baby boy of the family, Robert, named after his father. Standing next to them is Harold, and seated to his right is Robert Polk Starrett, the family patriarch.

In back next to Charlie is his brother Stanley, no longer wearing a Little Lord Fauntleroy outfit.

Charles V.E. Starrett, reporter

Two photographs of Starrett taken during war time.

The one on the left shows him on the troop ship “Kilpatrick” in April, 1914. Starrett covered the U.S. involvement in the Mexican uprising at Vera Cruz during 1914-1915. He had reached his full height, a little over six feet, and was lean for much of his life. The picture has been published several times, including Peter Ruber’s 1999 book for The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box Press, War Correspondent.

The photo of Starrett in uniform is from the family album. It is signed, “Faithlessly Yours,” (perhaps an in-joke) and dated May 18, 1918. Starrett had just left daily newspaper work in 1917. He had wanted to go to Europe to cover the Great War, but was sent to Washington, D.C. instead.

Vincent Starrett, author, ‘Dying Poet’ of the 20s

Vincent was proud of his good looks and had several studio portraits done during his professional lifetime. Here are two.

The one showing him looking thoughtfully into the distance is what he would later call his “dying poet” photo. It was taken in 1924. The lower right corner says it was taken by “Chambers, Mentor Building, Chicago.” The Mentor Building was (and is) a well-known office building in the city.

In Ruber’s The Last Bookman, Starrett says of this photo: “Here I look like a dying poet. Dying poets have a habit of becoming famous, but somehow I have defied this tradition.”

This other image was shot by Eugene Hutchinson. The profle shot was used in a 1929 clothing catalogue for Oppenheim’s of Jackson and Bay City, Michigan. Starrett had an article in the catalogue entitled, “Fashions in Fiction.“ The photo is also the icon for this blog. In both, Starrett’s hair has is clearly going gray. In 1929, he would have been 43.

There is also an iconic image from the late 20s and early 30s that has its own blog entry.

The photograph at the top of this blog post is probably from the early 1920s. It is a portrait by Chicago photographer Eugene Hutchinson. We will see his name again later.

Starrett’s hair is starting to show some gray during this period. This photo shows a streak of gray going through his hair, front to back. Starrett’s most famous detective, Jimmie Lavender, is described as having the same type of gray streak in his hair.

The Hutchinson picture was used in various publications, including the Blue Book magazine in 1928 which is what you see here.

Below is one more from this era, with Starrett in the back row at a Schlogl’s, a Chicago restaurant favored by newspaper reporters and editors. The occasion was a farewell party for Ben Hecht, who is standing left of Starrett. Hecht left Chicago for New York and later, Hollywood.

1930s: The world traveler

Photographs of Starrett during the 30s focus on his two-year around the world tour with Rachel (Ray) Latimer, the woman who would become his second wife. I have wallet-sized pictures from this period from the family photo album. If you click on the images, you will see a slightly larger version.

Distinguished author and husband: The 1940s

Vincent and Rachel Latimer Starrett

There is so much going on in this photograph, but I can only speculate on the circumstances. Starrett married Rachel on September 3, 1940. I believe this is a wedding photograph. But who were those others who were cut out of the photograph? And why were they cut out?

Vincent and Ray loved each other dearly, but her fragile emotional health often kept them apart.

Starrett must have preferred photographs that showed his right side. The portrait above was taken by Don Loving, who also shot the photo of Starrett in his fedora that is discussed elsewhere. This later portrait was used on the back of Books Alive, his 1940 book of bookish essays. Starrett’s hairline started to recede during the 1940s, when he entered his 50s.

Here’s one more studio portrait from the 1940s.

It’s another Don Loving portrait. Starrett’s hair, now almost all gray, continues to be full, although his hairline is higher.

You can find the portrait most prominently on the dust jacket back inner flap for Autolycus in Limbo, a collection of Starrett’s poetry. The 1943 book is most famous for being the first book publication of “221B.”

In 1943, Starrett was 57.

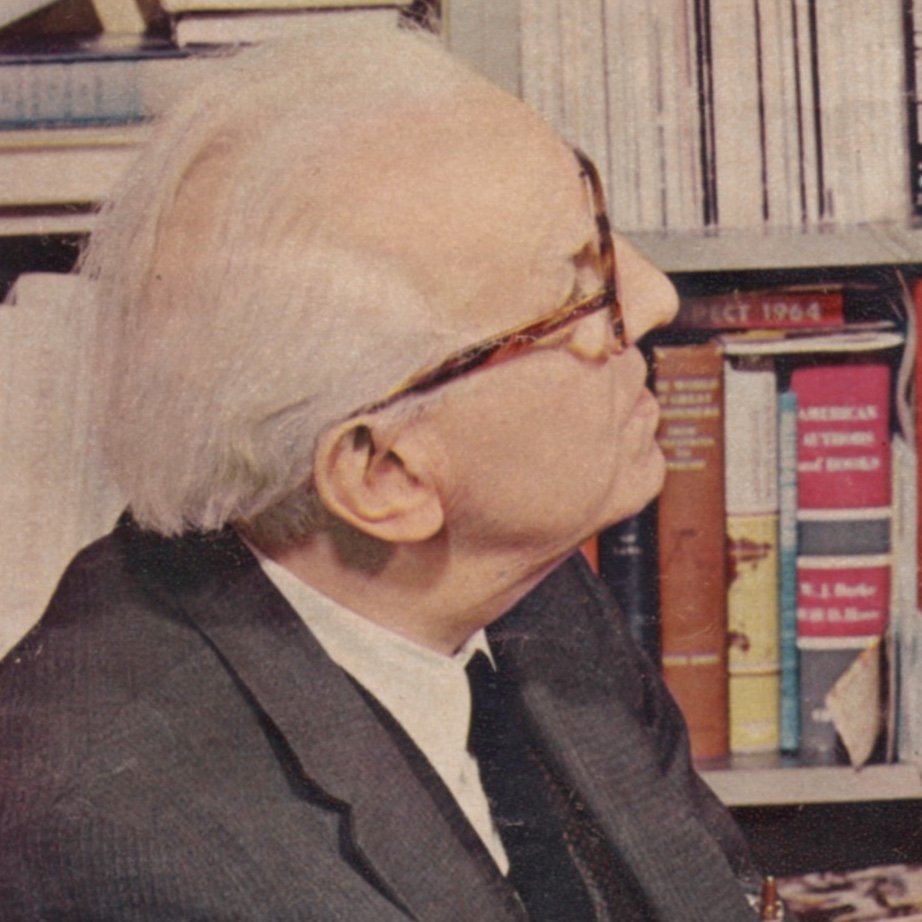

The later years

The 1950s were not a good time for Starrett’s personal life. Ray’s health continued to be precarious. Professionally, he was as prominent as ever. He had success as a columnist at the Chicago Tribune and with several writing and editing projects. But for the most part, he spent his time alone in his apartment, with his books as his only companions.

You will note that Starrett now wears glasses all the time. His eyesight was problematic in the 50s and worsened over his last 25 years.

I have found very few photographs of him from this time. The best I could do was a pair of grainy headshots from the Chicago Tribune. They were tiny. We used to call them thumbnails, for obvious reasons.

I was also able to find a better published version of the thumbnail on the right. It came from the Sunday Chicago Tribune Books Today magazine for January 10, 1965. This is a clipping from that newspaper and it has aged to a brownish yellow.

By the mid-60s, the photo was several years old, but was still being used to promote Starrett’s weekly column. The truth was that Starrett’s “Books Alive” column was winding down.

At the same time, Starrett’s abilities to keep up with a weekly column were fading as well. By 1965, he was 79 years old.

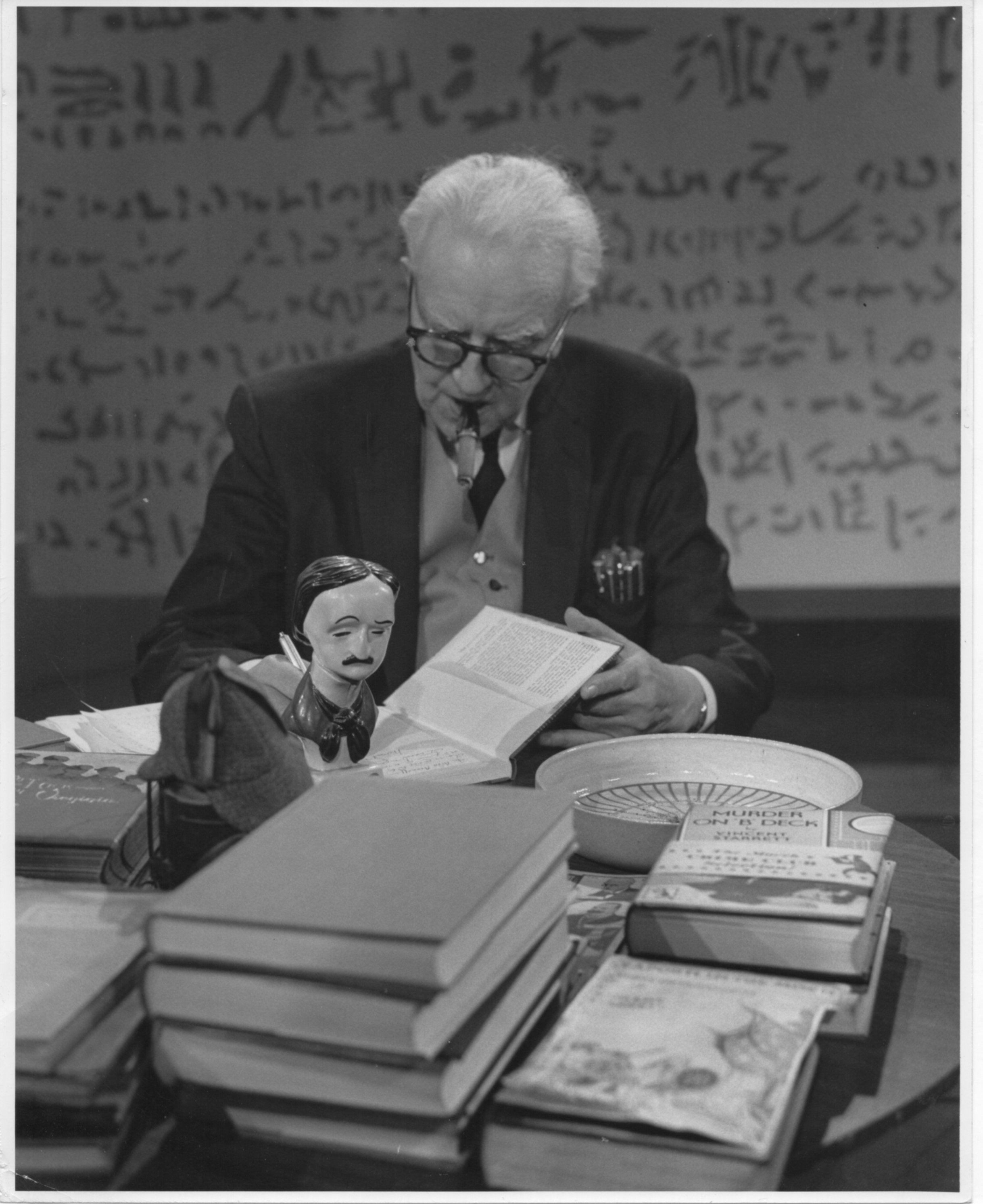

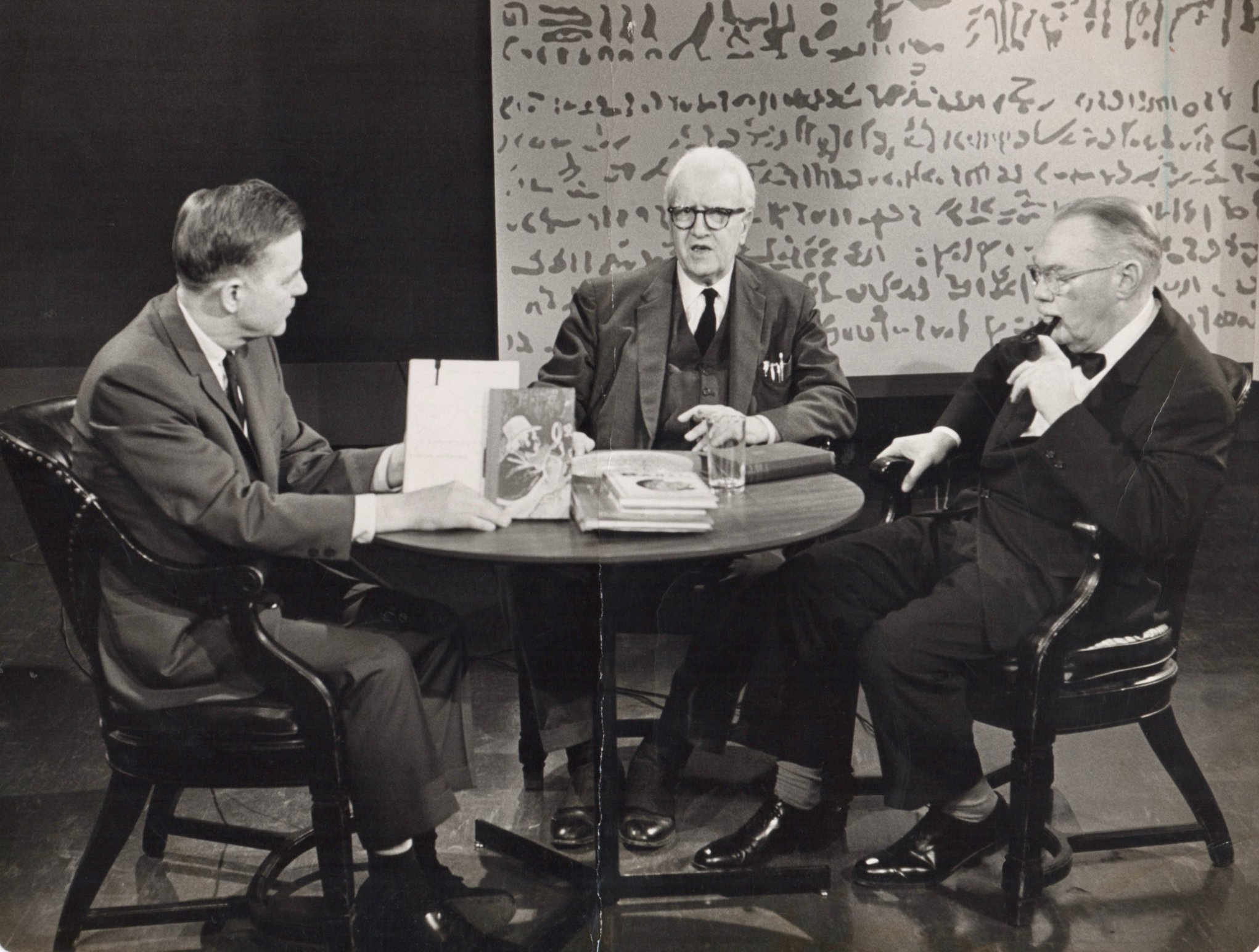

The 1960s were a kind of renaissance for Starrett. The Tribune treated him as a respected reminder of Chicago’s past, when gangsters ruled and New York felt threatened by the city’s wildly talented reporters, writers and poets. And the Baker Street Irregulars recognized him as the last of the group’s founding fathers.

Scroll over each image below for more information. You will also find three photos are from Starrett’s television appearance on “Book Beat.” You can find out more about that appearance here. And that photo with Rathbone and Irregular Robert Hahn is mentioned in this post. The last photo in the set, featuring a mature Starrett seated, came from a reader who found it among his mother’s possessions.

Final Days

The late 1960s and early 1970s were not good years for Starrett. He was losing his eyesight, was growing frail and did not like traveling the city’s bookshops. Many of his friends from his early years were passing away.

The love of his life, Ray, died in December 1969. Here’s an undated photo of the two of them in their later years.

One of the last pieces published under his name for the Chicago Tribune was “Portrait of the artist as an old dog,” a reflective piece about life, aging and literature. The subhead reads, “At 84, he knows there are some literary bones to pick, but it’s almost too late to get any meat off them. Still the wolves should know they are not his master. . .yet.”

It appeared in the Feb. 28, 1971 issue of the Sunday Chicago Tribune.

The article begins:

The titular figure of this sketch, this exercise in portraiture, is an old dog by anyone’s standards, having passed his 84th year to hell in recent weeks. But he is still, thankfully, this side of the line beyond which lives that undiscovered country nobody has lived or died to tell about.

The accompanying photograph shows his “good” side. His right eye was still operating although he suffered from cataracts. His left eye was largely useless. His nose has become more prominent, and his once great mop of hair has thinned considerably. He has also adopted a mustache. Other photos from this late period also show him with a beard or goatee.

Yet even at this age there is a regalness to his slim face. The lines in his forehead are finely etched and he seems to stare out into a world we can’t see.

The photograph is attributed only to Shargel.

When he died on January 5, 1974, the Tribune used a photo of Starrett that was clearly taken just a handful of years before. It showed him in a suit, with thick glasses, fading hair and the weight of years on his face.

But let’s not leave him like that.

Starrett in his home library in January, 1963. From a friend’s snapshot.

No, I prefer to think of Starrett like this, comfortable in his warm dressing gown, surrounded by his books, slippers nearby, and a warm cup of tea at hand.

Oh to be there with him, going through those shelves of wonder and mystery, while listening to him talk books and friends and Sherlock Holmes far into the cold winter’s morning.

That would be a memorable picture indeed.