The Bridge is Love

Starrett's copy of Thornton Wilder's classic

The endpapers to the first edition of The Bridge of San Luis Rey. Vincent Starrett’s copy with his bookplate.

A newspaper advertisement for Thornton Wilder’s lecture on The Bridge of San Luis Rey.

In the spring of 1929, the book-loving public in Chicago was agog over the speaking appearance of Thornton Wilder. Even those who were not bibliophiles knew that Wilder’s novel, The Bridge of San Luis Rey, had taken the Pulitzer Prize in 1928, after a year of riding the best sellers lists. A filmed version was rushed into production and would be released just a few weeks after Wilder spoke.

The Hotel Sherman had booked the celebrity author as the first in a planned series of literary events. Located across from City Hall, the splendiferous Hotel Sherman was supposedly the largest and grandest hotel in the U.S. outside of New York City. The building boasted 1600 guest rooms and a banquet hall that seated 2,500.

Legend has it that Chicago gang leaders of the early ‘20s met at the Hotel Sherman to work out an agreement that divided the illegal activities of the city into North Side and South Side mob districts. The Hotel Sherman Treaty would become the basis for a similar gathering described in The Godfather.

On April 14 1929, the 2500-seat ballroom was packed with Chicagolanders who had paid $2 each to get in. They got their money’s worth.

At 3 p.m., Vincent Starrett took his place at the microphone as the master of ceremonies to get the event rolling.

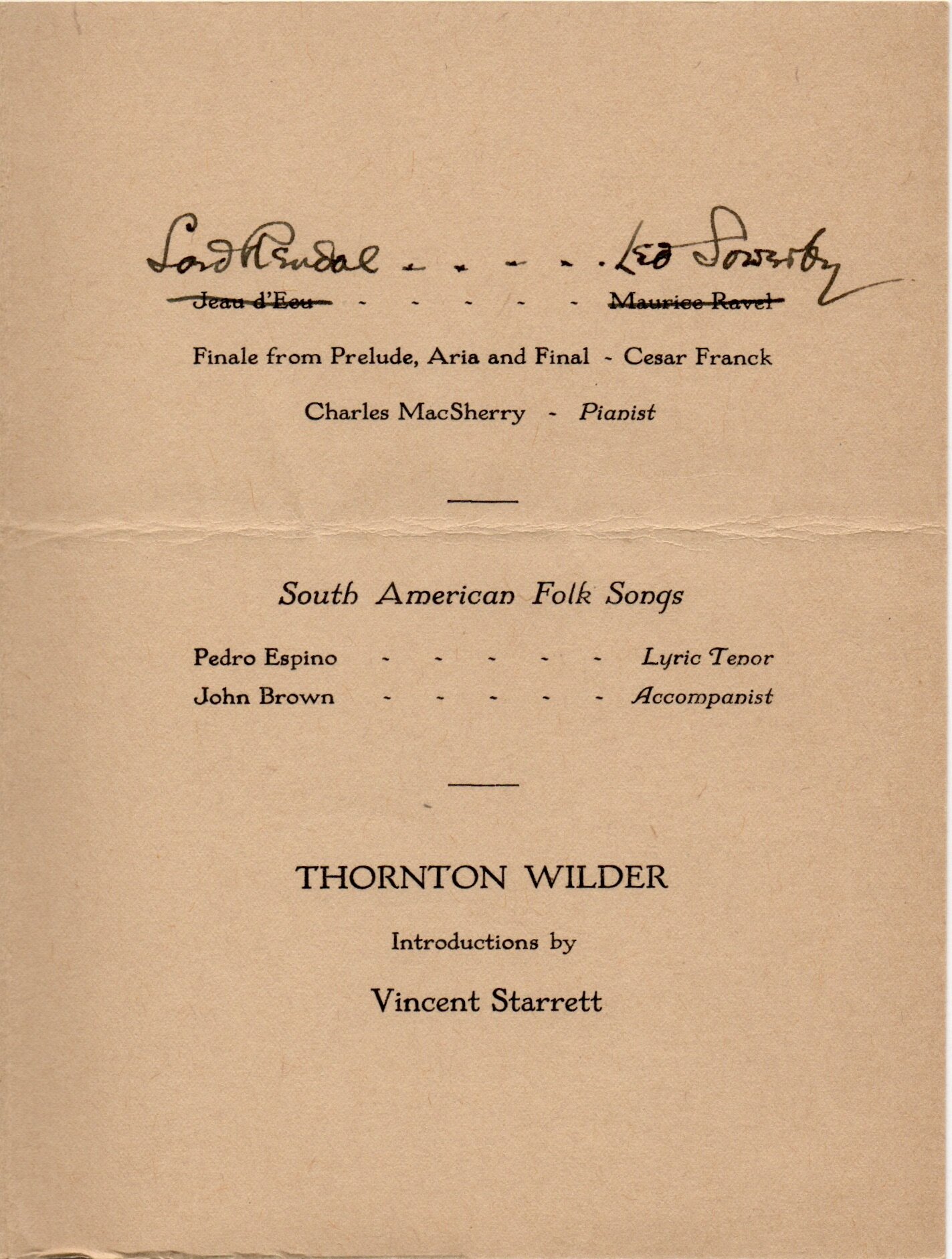

First came a few musical numbers. For some reason, the original selection of Maurice Ravel’s “Jeux d’Eau,” (misspelled in the program as “Jeau d’Eau”) was replaced with “Lord Rendal” by Leo Sowersby, followed by South American folk songs. (You can see the changes Starrett made in the program by clicking on the accompanying images.)

Then Starrett introduced the gathered crowd to one of the best-known writers of the day, Mr. Thornton Wilder.

The first edition dust jacket cover.

In a breathless column printed several days later in the Chicago Tribune’s book section, Fanny Butcher extolled Wilder’s comments that day as “the highlight of all literary lectures.”

“He told, quite informally, what ingredients of experience and observation and relationships had gone to make up The Bridge of San Luis Rey and then talked of the relationship between such a book, any book, and its readers and the result was as clarified and beautiful a thing as Bridge itself, as much literature as that undeniable masterpiece itself.”

The appearance was memorable in no small part because of Wilder’s well know desire for privacy. Butcher noted that Wilder is “shy to the point of distraction.”

Nonetheless, he stayed after the lecture, shaking the hands of his admirers and, in Butcher’s words, “autographing copies of his book, which will be willed to grandchildren.”

I did not get this first edition copy of The Bridge of San Luis Rey from my grandparents. It was purchased from a dealer and there is every reason to believe it was inscribed that April day from Wilder to the afternoon’s MC, Vincent Starrett.

Thornton Wilder came to Chicago in 1930 at the invitation of Robert Maynard Hutchins, the still new University of Chicago president. Wilder stayed for seven years, and during that time he and Starrett occasionally crossed paths.

How Starrett wound up as the MC for Wilder’s Chicago talk is unknown. Fanny Butcher, who frequently mentioned Starrett in her column and normally would make note of such a thing, seems to have been so blinded by Wilder’s address that she could not mention other incidental items of the day.

At any rate, Starrett had his copy of The Bridge of San Luis Rey signed by the author, and chucked his copy of the program into the volume. Both have been retained in subsequent years, and the volume now sits in a handsome box on the shelves behind me.

Starrett never explained how the two met, but they were both traveling in the city’s literary circles and it was only a matter of time before their paths crossed.

One such crossing took place in 1933 during the city’s Century of Progress. Starrett was “idling along the carnival highways” when a rickshaw pulled by a young man with a moustache came by. Starrett, who longed to be known for his poetry, recognized the women rider as Edna St. Vincent Millay. Wilder was the young man between the shafts pulling the contraption.

And, when Starrett turned around after the vehicle passed, he recognized none other than Alexander Woollcott sitting in back. Oh to have a photo of the look that must have been on Woollcott’s face!

In his memoirs, Starrett recalled another Wilder and Woollcott experience in the city. In 1935, Woollcott came to Chicago and during his visit did an broadcast of his Town Crier radio series. Starrett and Wilder were among Woollcott’s guests, which should not have been surprising. Remember that it was Starrett who invited Woollcott to the December 1934 Baker Street Irregulars dinner, much to Christopher Morley’s dismay. The event in Chicago was the last time Starrett saw Woollcott, who suffered a heart attack while on a radio show in 1943.

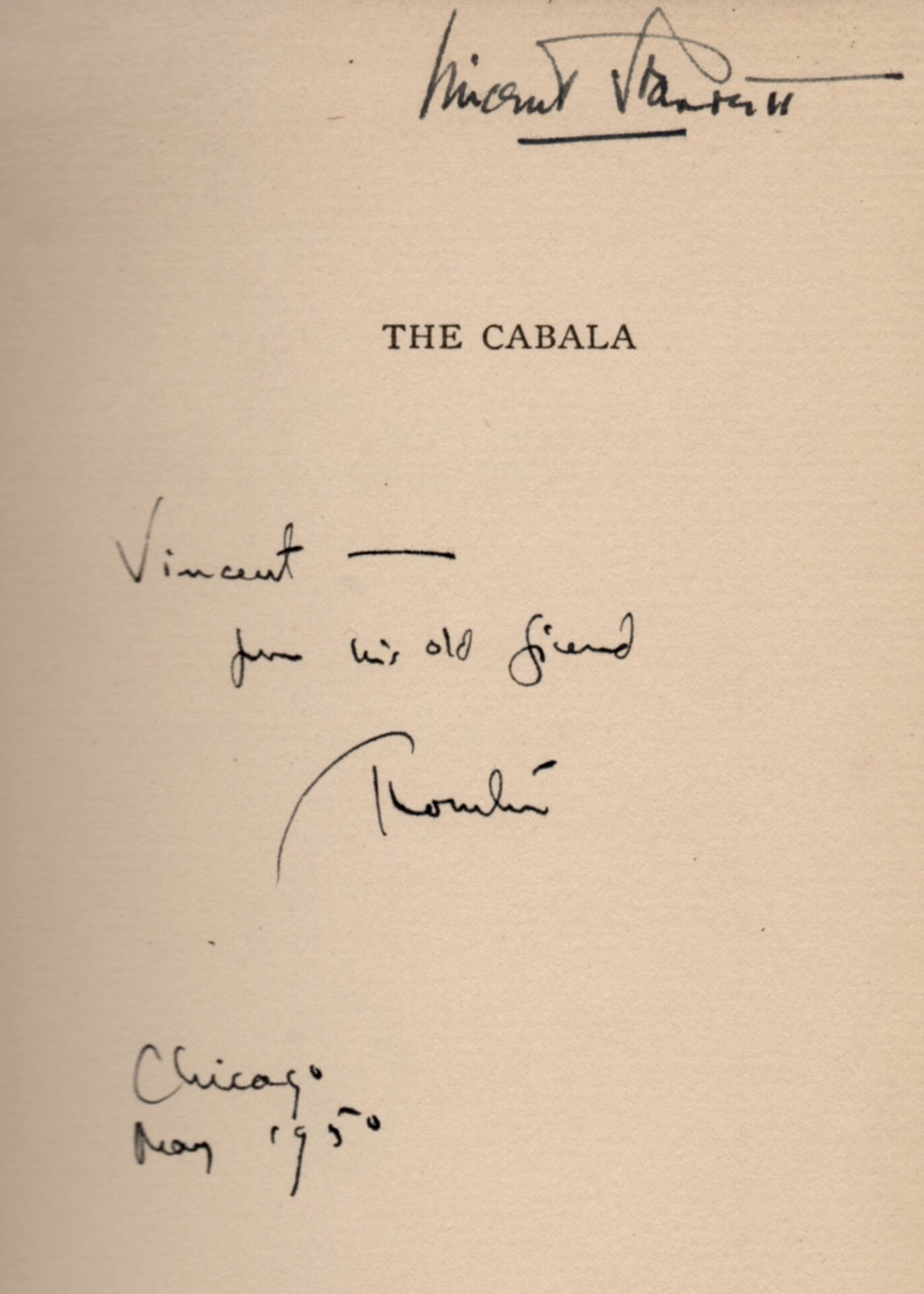

It was not the last time Starrett saw Wilder, as we know from the inscription the prize-winning author did for Starrett’s copy of another early work, The Cabala.

Here Wilder is more chummy in his inscription, showing a longer association between the two men. He signs the book to “Vincent, From his old friend Thornton.”

The Cabala was published in 1925, two years before The Bridge of San Luis Rey. It was not until 1950 that Starrett got Wilder’s signature on a copy.

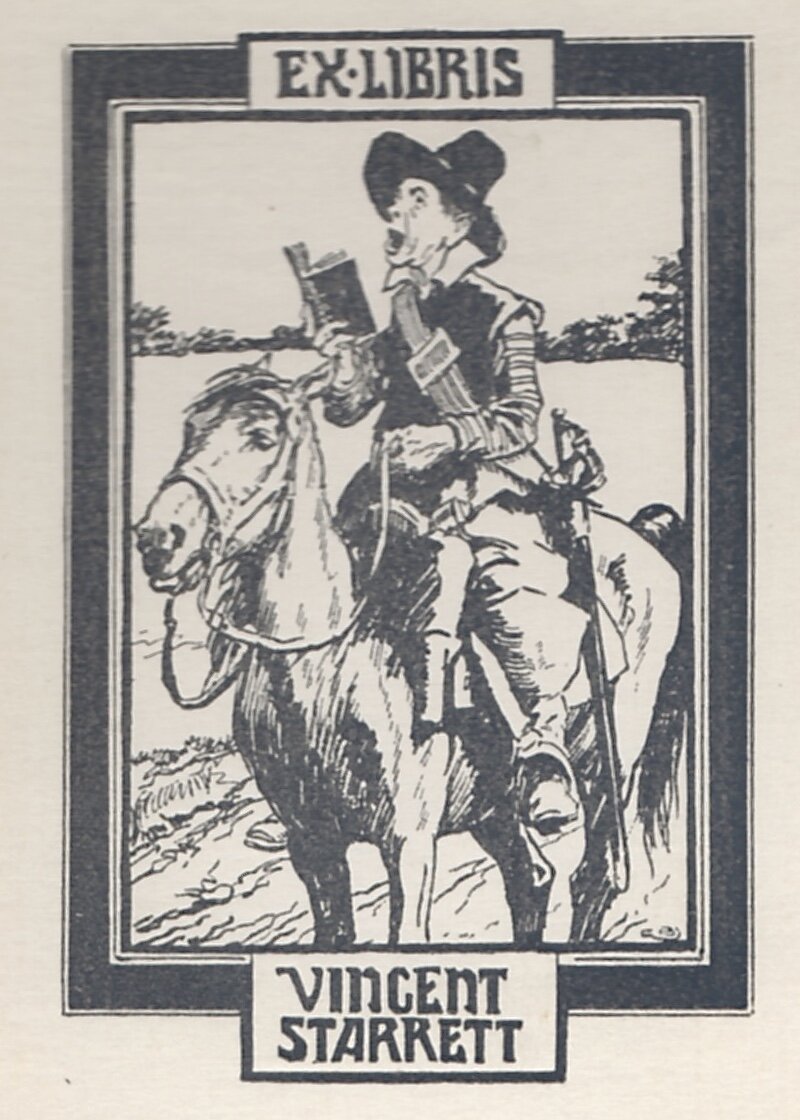

As is true of most of Starrett’s books, he also added one of his bookplates, this one showing a man reading—and apparently singing or talking—while on horseback.

You can find out more about The Cabala from this 2014 blog post.

Starrett came back to Wilder and The Bridge of San Luis Rey in 1955, when Bantam published his book, Best Loved Books of the Twentieth Century as a paperback.

The book is a collection of columns Starrett wrote for the Sunday magazine of Chicago Tribune the previous year. The 31st book he profiled was Wilder’s masterpiece. (The Hound of the Baskervilles was the second.)

The intervening years had not soured Starrett’s view of the Wilder’s most famous novel. He called The Bridge of San Luis Rey “one of the most provocative and original novels of our time.” Starrett discusses the book’s plot and characters and eventually comes, as many others have, to the sentiment expressed in the last lines of the novel.

And so do we.

The final lines from The Bridge of San Luis Rey.