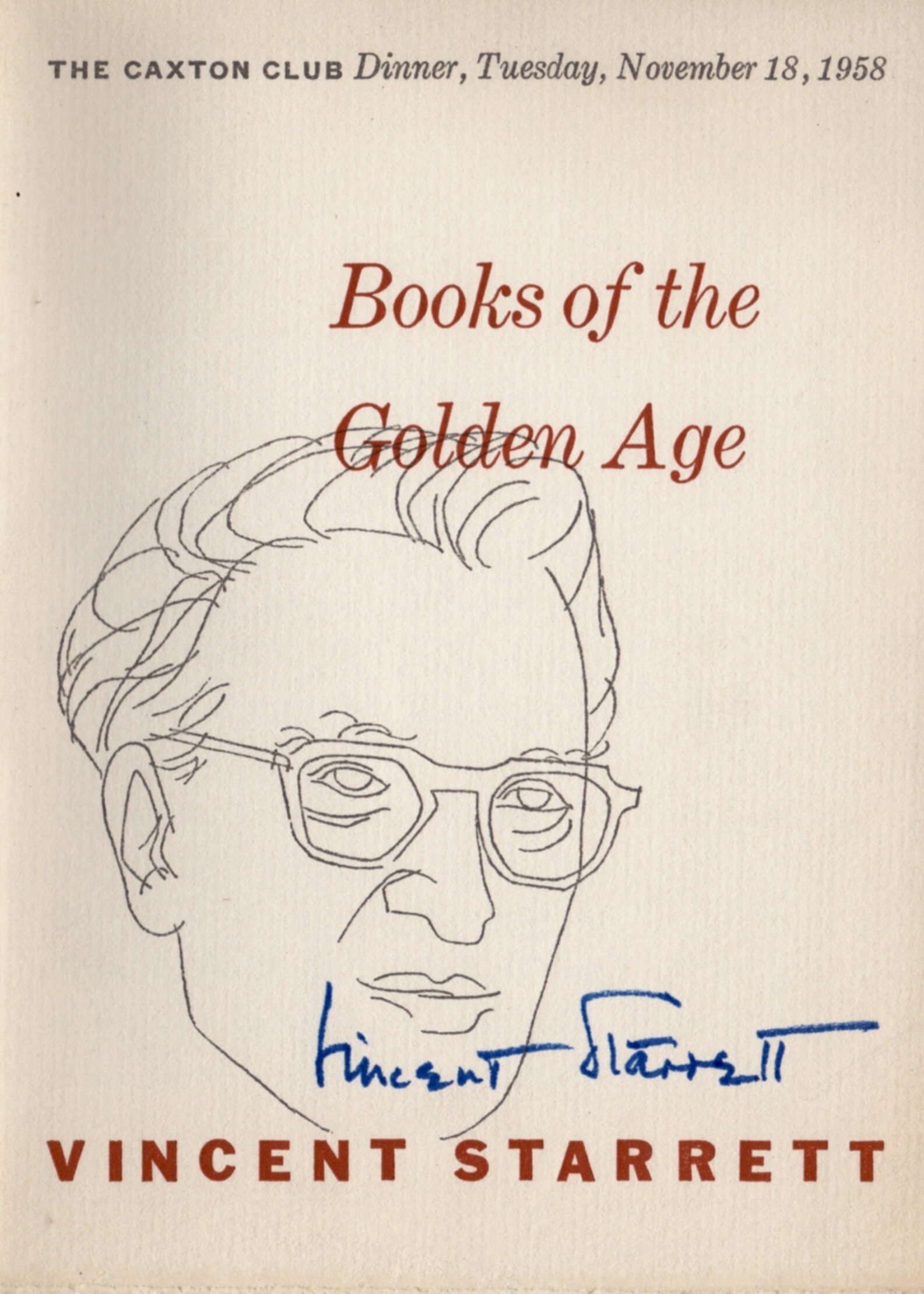

Books of the Golden Age

The joy of reading BEFORE the joys of collecting

It was a rainy day in March when I pulled down one of Charles Honce’s anthologies, Mark Twain’s Associated Press Speech, published by Honce in 1940 as a holiday gift to friends. Like his other anthologies, it is filled with stories Honce wrote for the Associated Press during his lifetime, seasoned with additional commentary and musings.

There is also more than a little bit about Vincent Starrett, to whom this edition is dedicated. This is not surprising, since Honce was Starrett’s bibliographer.

We’ll discuss this volume in detail another time, but to return to my rainy day read: I opened up the book to an essay by Starrett entitled, “Books of the Golden Age.” This gave me pause, and I stumbled over to my shelves, hunting for the thing that nudged my memory.

And there it was: A notice from the Caxton Club for dinner on Tuesday, November 18, 1958 at the Cliff Dweller’s Club in Chicago. (My copy, reproduced here, has Starrett’s name in blue felt tip marker, assuredly NOT from Starrett himself.)

It is entirely possible that notes from that Caxton Club event are housed at the Newberry Library where the club’s archives now dwell. And perhaps in that collection is a summary of Starrett’s talk, which would be wonderful, since one could then compare the talk with the essay published 18 years earlier as the preface to Honce’s holiday book.

But after noodling around a bit, I came to discover that the title, if not the text, is older than it first appears. Starrett had an essay in a long-forgotten journal entitled The Freeman. That essay was published in the spring of 1922, 18 years before Honce’s book and a full 36 years before the Caxton Club dinner. I wasn’t able to see the text of The Freeman for that issue online, but it would not surprise me if Starrett used parts of the same essay from 1922 in 1940 and 1958.

As I have observed before, Starrett was recycling long before it was fashionable. (Indeed, it’s entirely possible the essay exists in one or more of Starrett’s books on books, although a cursory review did not pull it up.)

It is also possible his essay evolved over time, even if the title did not. For example, Starrett mentions here that he first read the Holmes short stories “40 years ago.” Elsewhere, he says he read first found Holmes at the age of 10, or 1896. That would place this version of the essay at 1936, four years before the book’s publication. Which raises another question: Did he update the essay in 1936 for another publication, and then give it to Honce for use in his 1940 book?

And what, if anything did he update when he read his essay by the same title to the Caxton Club in 1958?

(If the water wasn’t so muddied, I would toss in a few observations from a Nov. 17, 1957 article he wrote for The Chicago Tribune with the awkward sounding headline: “Books of a Golden Age: Ones Read in Childhood.”)

All of this is prologue to the essay itself, which I offer here in full, because it’s a simple delight to read.

Sherlockians looking for something of interest will find it here, as Starrett briefly describes his first meeting with Sherlock Holmes, which in itself is worth comment. There is much more too, especially about his early reading habits.

Bits and pieces of this would end up recycled again in Born in a Bookshop, Starrett’s 1960 book of memoirs. But it is a pleasure to offer it here in full, and to imagine a time in Starrett’s life when he read books for the unadulterated pleasure of reading, and not as a bookman evaluating the volume for it’s bibliographic worth.

Enjoy.

Books of the Golden Age

There was a time, it is surprising now to remember, when I had never heard of the magic words “First Edition.” I often wonder if I was happier then. Possibly so—but it is difficult to compare one happiness with another. I am quite happy now as, burdened with much dubious wisdom about “points” and prefaces, I contemplate the long record of my bibliodyssey, and know that I am still a damned old fool about books.

And my book room—which seems to grow smaller, instead of larger, with the years—is a pleasant place in which to rationalize my lunacy, after more than a quarter of a century of secret competition with Mr. Morgan and Dr. Rosenbach. I say secret advisedly, for of course neither Mr. Morgan nor Dr. Rosenbach was ever acutely aware of my existence. We lived on different levels of the mountain. But it was the same mountain; and I think our objectives were the same. That is to say, we wanted for our personal and private collections all the great and rare books of the world upon which it was possible to lay our greedy hands. The difference between us, for the beginning, has been just this: my distinguished competitors, for the most part, got what they wanted, and I, for the most part, got what a far leaner purse permitted.

Of one thing I am quite sure, however: from no other diversion in life have I had such enduring pleasure as from collecting books.

“There are evenings when I would rather re-read Rider Haggard than Somerset Maugham. ”

But in that other time there was much happiness too. It was then possible to read with a single-minded pleasure — for the story and its telling, for the sheer uncritical love of reading. How much of that early rapture is gone with the years I do not know; and it is a question that sometimes troubles me. The small boy who for the first time read “A Scandal in Bohemia” and “The Speckled Band,” on a doorstep in Toronto, was not aware that the volume in his perspiring hand was just a shabby reprint. He had not noted the date on the title-page, to check it against the date of the copyright. If there were advertisements at the back, they were simply advertisements of further entertainment, not clues to the mysteries of publication. It is even possible that, after the first few pages, he did not remember the author’s name, although on that score I hope I may be wrong.

“At any rate, there was an early copy of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. I read the thing to tatters, and so embarked on a career of Conan Doyle idolatry that I am happy to say still flourishes. ”

That was forty years ago; a long time in any life. Even then I as a collector; but I didn’t know it. I collected books, not editions, and kept them on a shelf convenient to the bed that I occupied jointly with a younger brother. There were some interesting items in that early miscellany, as I recall it, including an old book of colored flies—the real thing—that had belonged to my grandfather, a noted fisherman. Upstairs, in a corner of the low-ceilinged, many angled attic, was an old bookcase stuffed with volumes of every description; the surviving veterans, I suppose, of several generations of avid readers. Occasionally I looted this, sneaking out possible-looking stories to stand on my personal shelf; but I fancy I missed all the good ones. The good ones, I mean, from a collector’s point of view. My blessed aunts! How I should like to do it all over again. Years afterward, I found what was left of them, in an old trunk, and saved a handful for my more mature collection. The first that came to hand—in rather decent shape, considering—was an indubitable original of The Age of Fable; but I am confident there must once have been a Scarlet Letter and a dozen early Emersons. Perhaps even a Moby Dick, although generally the books were in English in origin.

“Of one thing I am quite sure, however: from no other diversion in life have I had such enduring pleasure as from collecting books.”

Nobody else in the family ever had troubled to “collect.” They bought to read and to discuss, and then consigned the volumes to the attic. It was a curious jumble, that old bookcase at the head of the stairs. Reading in catalogues—a profitless and delightful waste of time, when one is sentimental—has since recalled for me some of the titles it contained, which once attracted me: The Silence of Dean Maitland, Concerning Isabel Carnaby, A Romance of Two Worlds, Ships that Pass in the Night, The First Violin. I tried to read them all, at one time and another; but I have long forgotten—if I ever knew—what occasioned the silence of Dean Maitland. I do remember that the Harraden novel had nothing in it about ships. You will think, perhaps, in the light of this reminiscence, that my various aunts and antecedents were unembarrassed by any very notable literary taste; but that is to do them an injustice. I have perversely remembered only a handful of the more ephemeral tales. At any rate, there was an early copy of The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. I read the thing to tatters, and so embarked on a career of Conan Doyle idolatry that I am happy to say still flourishes.

“I am sorry for the collector who, at any time, begins to blush for his early taste; and who in consequence released books that have been part of his youth”

What else I read in those pleasant days was largely juvenile melodrama—Kingston and Ballantyne, and Henty and Manville Fenn, and dear old David Ker of the Boys’ Own Paper, a delicious British weekly seldom seen on this side of the water. When I first began to “collect” —in quotation marks— I blushed to see the number of adventure stories that still stood upon my shelves It occurred to me that it was time for me to grow up; and in an evil moment I got rid of them. I have kicked myself briskly for that piece of folly many times since it was perpetrated. That early sophistication of the young collector! It is as unsophisticated as it is premature and reckless. I wish now I had them back—some of them—for there are evenings when I would rather re-read Rider Haggard than Somerset Maugham. They were not all “first,” of course; but many of them must have been—and there are books that one should own in paper reprint rather than own not at all.

Now and then, after the years of separation, one of my old favorites—the actual book itself—turns up in the pages of a second-hand catalogue, with my signature on its halt-title and my old label pasted to its inner board; and when the mood is right I buy it back. Always when this happens, I like to think there is a grateful gleam in its eye.

“The small boy who for the first time read “A Scandal in Bohemia” and “The Speckled Band,” on a doorstep in Toronto, was not aware that the volume in his perspiring hand was just a shabby reprint.”

I am sorry for the collector who, at any time, begins to blush for his early taste; and who in consequence released books that have been part of his youth—no doubt part of his growth. Inevitably he will want them back again; not all of them, of course, but those he remembers with peculiar pleasure. Those sterling works of derring-do, the very sound of whose titles warms the heart like old wine—how poignantly they allure, after he has lost them! When again he has them—in crisp, expensive first edition—he may discover that they are not precisely all that memory made of them. They never were, in point of fact; but that is not important. The second time, at least, they should be kept, if not to read, at any rate to handle; or, indeed, as a matter of self-protection, lest the whole episode happen over again.

“There will be moods and evenings when nothing else will do save only these old tales of childhood; one need only wait the hour.”

Be that as it may, there will be moods and evenings when nothing else will do save only these old tales of childhood; one need only wait the hour. I have enormous pleasure re-reading, about once a year, two or three of the books that captured me in youth; and they have seldom failed me. If I did not have them beside me I should want to read them oftener—or think I did. It may be, of course, that if I were reading them for the first time I should be less rapturous—I find analogous books of the hour quite stupid—but it is difficult to believe there may ever come a day when The Coral Island and The Cornet of Horse will fail to delight me.

Vincent Starrett