'Sincerely yours, S.C. Roberts'

Roberts and Starrett: “A quartering of the Union Jack with the Stars and Stripes.”

It was the Spring of 1941, and England was under attack.

Nightly bombings of Britain had started one year earlier, and by the fall of 1940, regular raids began on London. The Winter of 1940-41 saw attacks of British industrial cities as Germany tried to neuter the British ability to build aircraft and other weaponry. Early 1941 saw devastating bombing raids on London and the nation’s port cities.

But in Cambridge, the operations of the University Press went ahead, under the careful eye of longtime secretary Sydney Castle (more commonly S.C.) Roberts. An early Holmes commentator, Roberts brought his classical education to the playful study of the Sherlockian Canon.

Sitting at this desk, Roberts wrote a letter to Vincent Starrett, who had asked if Roberts could supply a copy of the rare 1929 booklet, A Note on the Watson Problem.

Starrett had sold off a large part of his Holmes collection and was diligently working to restore it to its former glory. War or no war, the old bookman pushed forward in his quest.

I was recently able to purchase Roberts’s letter, and the little booklet itself, with Starrett’s notes inside. So I thought this would be a good opportunity to take a look at these two men who were separated by an ocean, but united in their passion for books and Sherlock Holmes.

Starrett had been aware of Roberts’s interest in Sherlockian scholarship for some time. On April 15, 1931, Starrett wrote to Dr. Gray Chandler Briggs, who was helping Starrett with the book that would become The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. (This letter comes from Dear Starrett—/Dear Briggs—, published in 1989 by the Baker Street Irregulars.)

Here’s Starrett’s note:

Dear Briggs –

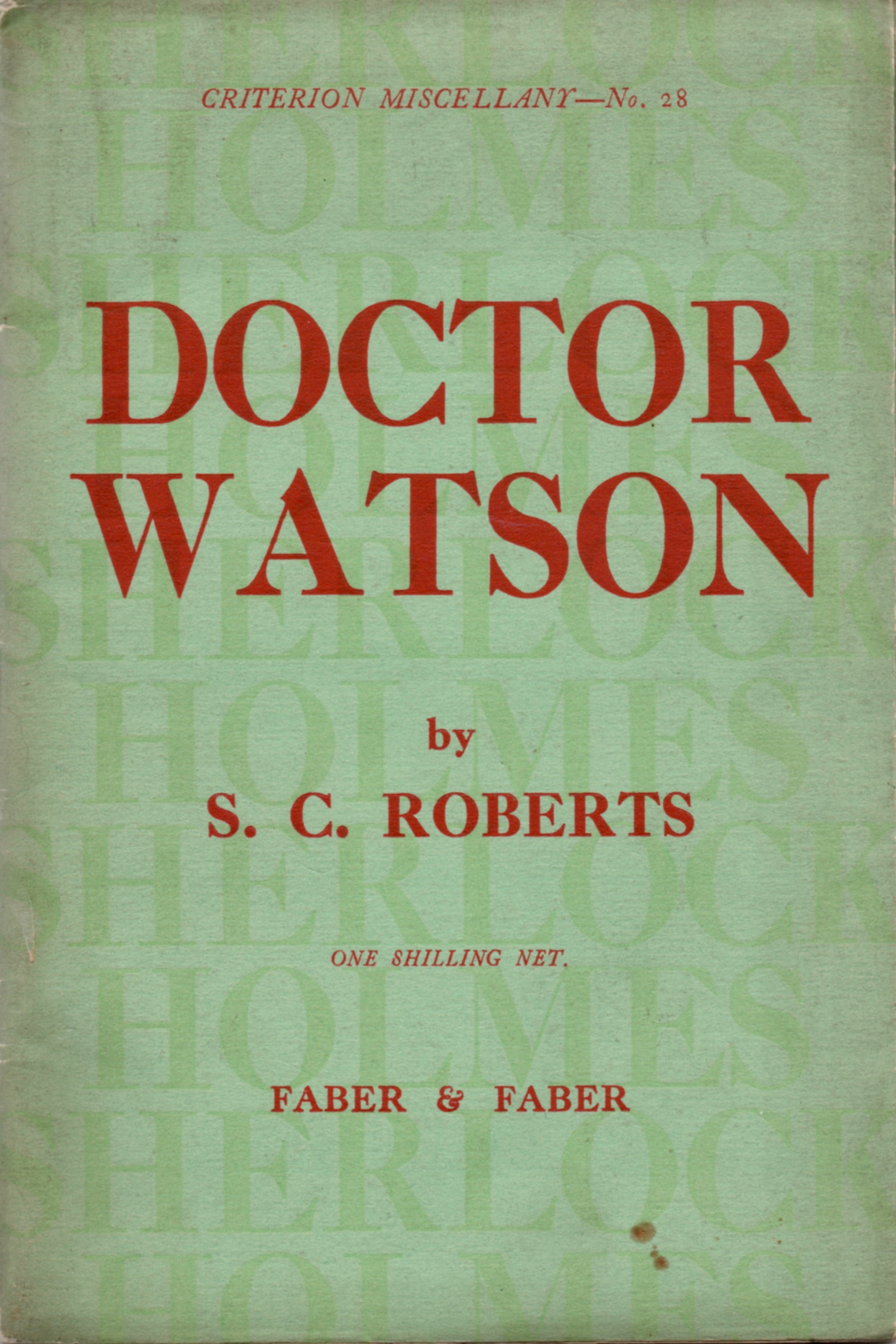

Are you acquainted with Dr. Watson (by S.C. Roberts) a monograph recently published in England? You are mentioned in a footnote as identifying Holmes’s rooms in Baker Street.

If you haven’t seen this delightful bit, I’d like to send you one, shortly, when two copies that I have ordered arrive from London.

(The full title of Robert’s booklet is Doctor Watson: Prolegomena to the study of a biographical problem, with a bibliography of Sherlock Holmes. Glance at the bottom of this essay for a note on the influence of that title.)

In a later letter to Briggs, Starrett adds that in addition to Doctor Watson, he also owned the earlier Roberts essay, A Note on the Watson Problem. (As you will see below, that’s the pamphlet Starrett was hoping Roberts could help restore to his collection.)

Both books are classics of Golden Age commentary, picking up where Msgr. Ronald Knox left off with his 1921 essay, “Studies in the Literature of Sherlock Holmes.” Roberts, who published books on Samuel Johnson, Lord Macaulay, George Lyttleton and other eminent men of an earlier era, brought the same devotion to detail to his Holmesian investigations. His writings remain classics of their era and continue to entertain today.

While we don't have Starrett’s letter to Roberts, it would seem that he explained to Roberts his need to sell his Holmes collection and a desire to start all over. Here’s a transcription of Roberts’s reply:

University Press, Cambridge

19 April 1941

Dear Mr. Starrett

I enclose a copy of “A Note on the Watson Problem” with great pleasure, but am afraid I must hang on to my one spare copy of “Christmas Eve.” I’m sorry you were obliged to sell out, but you will have some fun in re-building.

I hope we shall enjoy the same sensation after the war. Cambridge has been lucky so far — only an occasional small attack. London & other places are pretty grim, but full of fight & spirit.

I wish people like Rex Stout, whoever he is, wouldn’t write nonsense in the Saturday Review of Literature. They spoil the whole game.

Sincerely yours.

S.C. Roberts

The 1953 collection of S.C. Roberts’ commentary on the Holmes canon.

A few observations on the letter:

“Christmas Eve” was a brief play written by Roberts and privately printed. It is now quite rare in its original state. I don’t know if Starrett ever found a copy, but he could have read it some 20 years later in the wonderful book, Holmes & Watson: A Miscellany, published in 1953 by Oxford University Press.

Holmes & Watson gathers many of Roberts’s writings about Holmes, including the “Christmas Eve” play, his earlier exegesis on Watson and Holmes, and the pastiche, “The Strange Case of the Megatherium Deaths.” There have been several reprints, including a paperback edition by Otto Penzler.

You should own a copy.

Cambridge was not an object of frequent Nazi bombings, but like all of England, suffered under the privations that came with the war. Roberts is exhibiting the best of the “stiff upper lip” pattern than Americans wanted to hear from their British cousins:

“London & other places are pretty grim, but full of fight & spirit,” might have influenced Starrett’s thinking when it came to writing his 1942 sonnet, “221B”: “England is still England yet, for all our fears.”“Rex Stout, whoever he is.”

The sentence leads me to believe that Nero Wolfe had not made his way to the rarefied air of Cambridge. Roberts soundly thumps Stout, whose tongue-in-cheek essay, “Watson was a Woman,” was delivered at the Jan. 31, 1941, Baker Street Irregulars dinner to “mixed emotions and produced heated discussion,” according to Edgar W. Smith’s notes.

Stout’s paper was published in the March 1, 1941 issue of The Saturday Review of Literature, where Chris Morley held sway. The essay continues to draw heat and has been reprinted widely, including Smith’s anthology, Profile by Gaslight, published in 1944 by Simon and Schuster.

As you can see from the dust jacket, Starrett and Roberts were together in this 1934 anthology.

I don’t know if there were other letters between Starrett and Roberts discussing their mutual Holmes affection during this period. There is one Starrett/Roberts letter at the University of Minnesota collection, but it is dated 1905, long before either man began writing about Holmes. If you know of additional correspondence, please drop me a note.

It’s worth noting the two men appeared in the same anthology in 1934, Baker Street Studies, published in a limited edition of 500 copies by Constable & Co. Ltd of London. Starrett contributed “The Singular Adventures of Martha Hudson,” and Roberts offered “Sherlock Holmes and the Fair Sex.”

This is another classic of Golden Age commentary and should be on your shelves. If the first edition is too pricey, there have been multiple reprints over the years.

The 1955 reprint of Baker Street Studies with contributions by Roberts and Starrett.

A bit more on the fellow from Cambridge.

Roberts had a distinguished career. He continued as secretary of the Cambridge University Press until 1948. He was named a master of Pembroke College, Cambridge, from 1948 to 1958; vice-chancellor of the University of Cambridge from 1949 to 1951; and then chairman of the British Film Institute from 1952 to 1956, when he was knighted.

In 1951, Sir Sydney became the first president of Sherlock Holmes Society of London, a role he retained until 1966.

Throughout his lifetime, he continued to write about his favorite leading men in the world of British literature: Boswell, Johnson, Macaulay and Holmes.

Sir Sydney died on July 21, 1966 at the age of 79.

One more bit.

You might have noticed the unusual full title of Roberts’s monograph, Doctor Watson: Prolegomena to the study of a biographical problem.

The first time I read the word “prolegomena” I had to look it up, and discovered it means a critical introduction. The word must have also struck the fancy of BSI leader Edgar W. Smith, since he borrowed it in 1953 for his own bit of biographical exegesis, The Napoleon of Crime: Prolegomena to a memoir of Professor James Moriarty, Sc.D.

I was fortunate to pick up a copy of Smith’s booklet a while back. The best part? This is Julian Wolff’s copy, with his bookplate affixed.

From Starrett to Roberts to Stout to Morley to Smith to Wolff. Our Sherlockian family tree is a long one and the links are many.