The Crane Competition

The sad tale of a Stephen Crane bibliographer

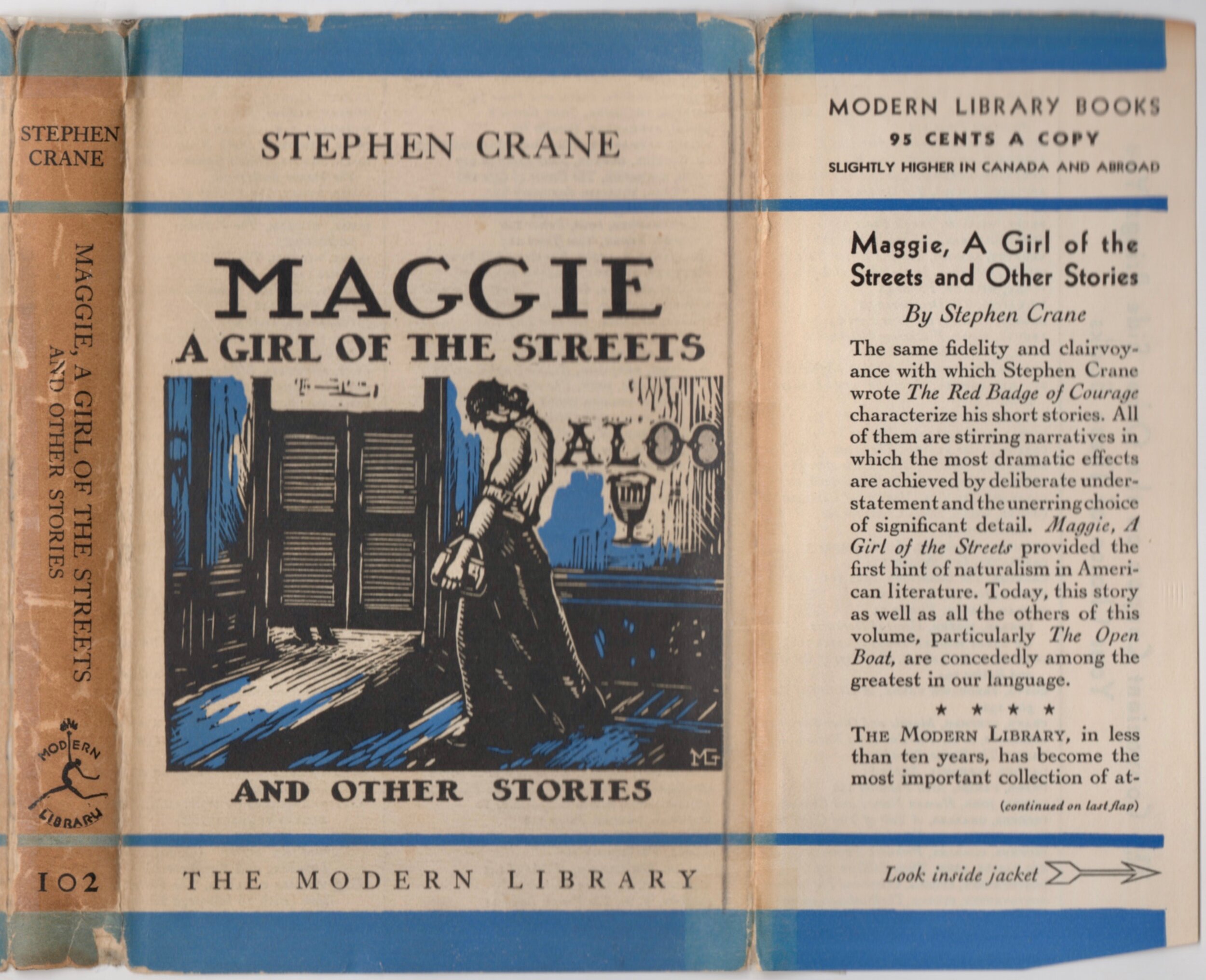

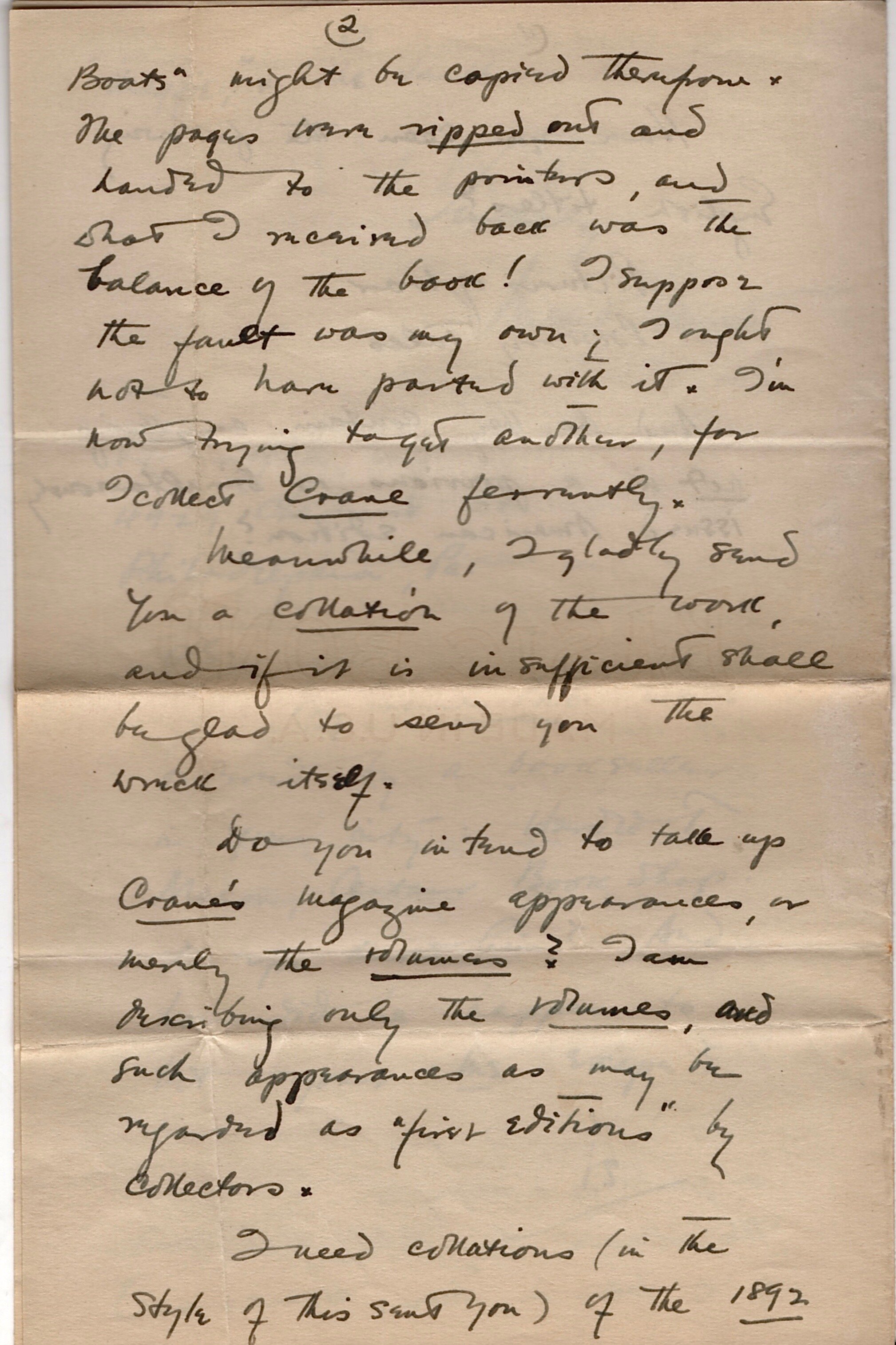

Cover for the 1923 bibliography of Stephen Crane by Starrett, published in Philadelphia by The Centaur Book Shop. There are two states: one measuring 7 3/4 by 5; and a big sister edition coming in at 9 1/2 by 6 1/4. The smaller trade edition was 350 copies; the larger issue had just 35.

Part 1: in which we meet Mr. Griffith of Philadelphia

Imagine, if you will, spending three years of your life researching a new book, a bibliography of a famous writer. You work with book dealers and collectors, publishers and other enthusiasts. You contact the writer’s friends and get details of his life and stories that only they know.

And then, just as you’re ready to hunt for a publisher, you get a letter from an amateur in Chicago who has spent barely three months on the same subject, who already has a publisher (in your own city, no less!), and has the nerve to ask YOU for information for HIS competing bibliography.

Ladies and gentlemen, let me introduce you to the most unfortunate bibliographer-in-waiting ever, Mr. O. (possibly Oram) L. Griffith of Philadelphia, Pa.

Part 2: We learn more of his commitment to a bibliography

In the early 1920s, Mr. Griffith was on the leading edge of the Stephen Crane appreciation wave.

Americans were discovering the works of the recently deceased writer whose books, like The Red Badge of Courage and Maggie: A Girl of the Streets were being recognized as an original American literary voice.

Griffith had built a large Crane collection and progress on his bibliography manuscript was rolling along rather well until he received a June 29, 1922 letter from Chicago.

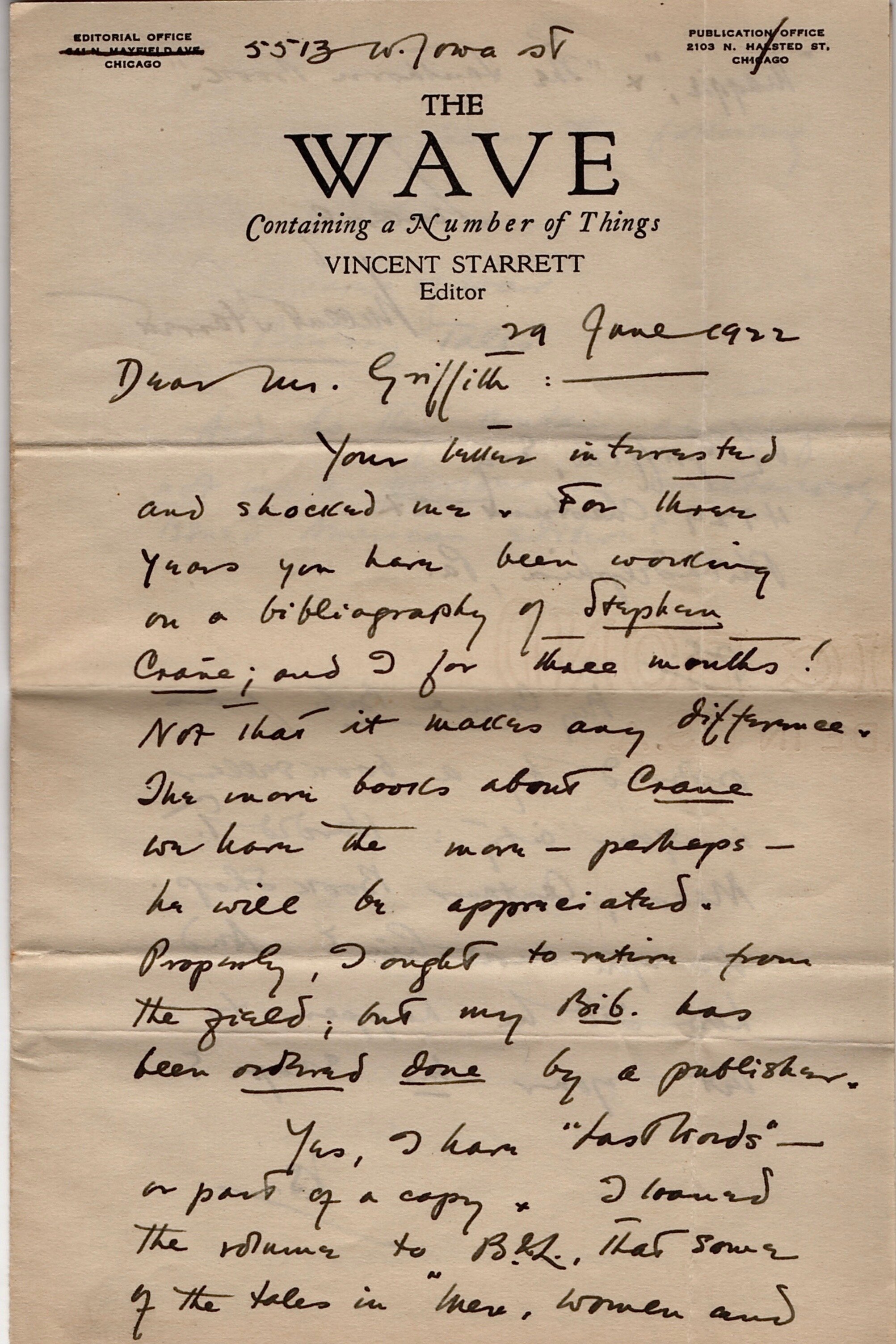

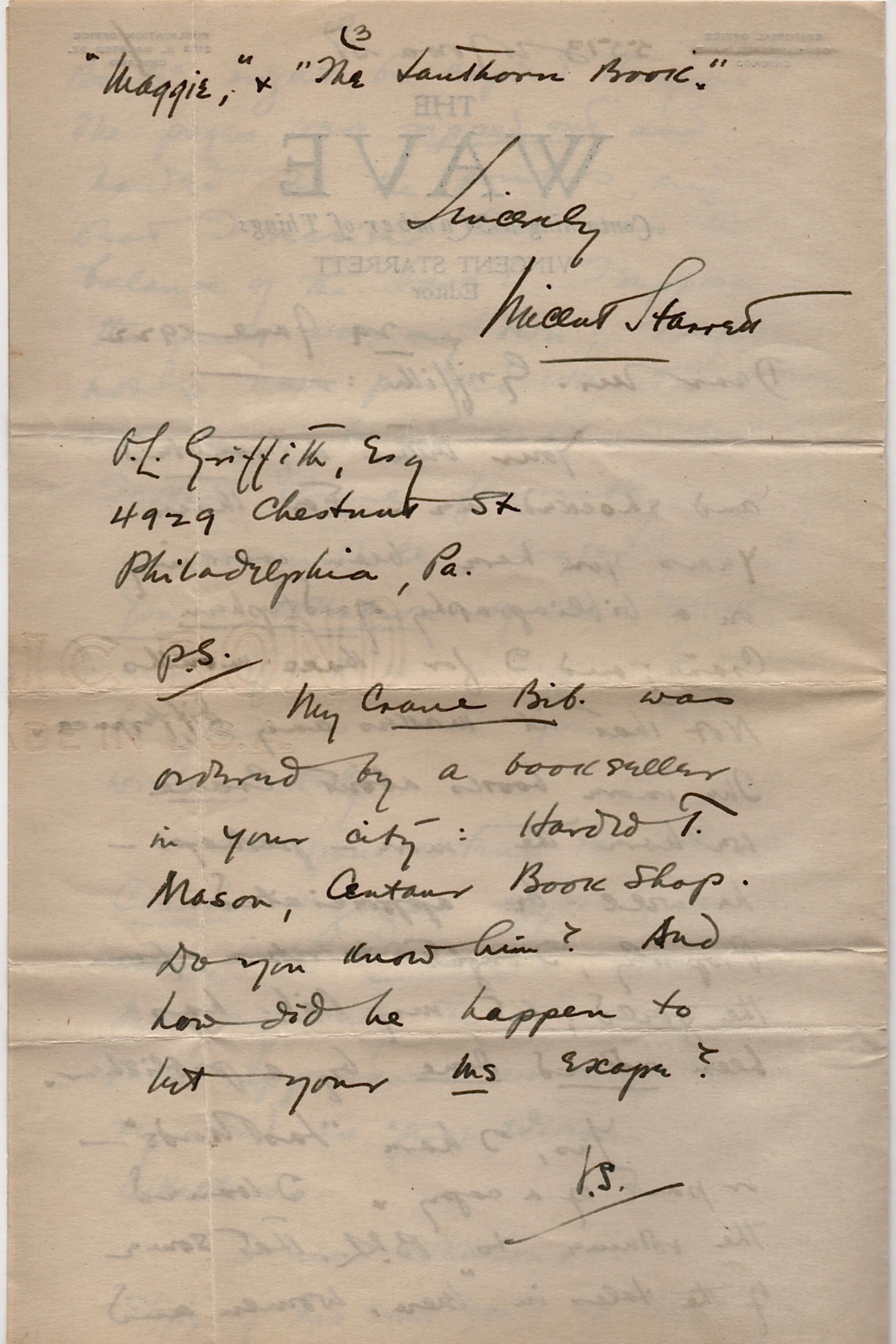

“Your letter interested and shocked me,” wrote Vincent Starrett on the letterhead of his little magazine The Wave.

“For three years you have been working on a bibliography of Stephen Crane; and I for three months! Not that it makes any difference. The more books about Crane we have the more—perhaps—he will be appreciated. Properly, I ought to retire from the field; but my bib(liography) has been ordered done by a publisher.”

(Both Starrett and Griffith abbreviate bibliography to bib., which I find annoying. Hence the use of “bib(liography)” above and elsewhere when quoting from their letters, a usage which I acknowledge as only slightly less annoying.)

Starrett offers Griffith a page of Crane-related book talk and then adds this little postscript:

“My Crane bib(liography) was ordered by a bookman in your city: Harold T. Mason, Centaur Book Shop. Do you know him? And how did he happen to let your MS escape?”

Oh, the agony! The bibliophilic pain! To work for years on a project and find out that an upstart from Chicago has beaten you to the finish must have galled Griffith. We don’t have the full correspondence of the two men, (there must have been a letter from Griffith to Starrett to prompt this reply, for example) but we have enough to give us a good illustration of what went on between them.

Part 3: How we came to know this sad tale

Starrett’s inscription on Griffth’s copy of Stephen Crane. The folded lined sheet of paper below the inscription is the handwritten note from Starrett seen below.

And here is as good a place as any to pause and explain how I came upon these letters.

I purchased at auction several months back a collection of Starrett’s works from Cornelis Helling, a Swedish Sherlockian. Helling was a long-time Holmes devotee and was invested into the Baker Street Irregulars in 1961 as The Reigning Family of Holland. So far as I can tell he never came to the U.S.

At some point Helling picked up a copy of Starrett’s 1923 book, Stephen Crane: A Bibliography. Tipped into the book are four letters from Starrett and one letter in response from Griffith.

The book has an inscription in the front free end paper:

“For O.L. Griffith/With kindest regard/Vincent Starrett/March 1923.”

Accompanying the text are penciled notes (presumably in Griffith’s hand) which point out every error Starrett has published. And, in Griffith’s view, there were many, many errors.

Part 4: The indignation of Mr. Griffith

A sample page from Starrett’s bibliography, with some of Griffith’s notations.

“This is wrong,” writes Griffith about the book Starrett identified as the first edition of Maggie. He continues:

“Appleton’s changed the title page to correspond with Red Badge & projected Little Regiment so as to have the volumes uniform.”

You can practically hear Griffith sniffing with disdain at Starrett’s error. This is just one of numerous such notes which show Griffith’s growing indignation.

But that’s for the future. The correspondence between the two men salvaged here takes place in the autumn before the book was published.

Part 5: An attempt to cooperate?

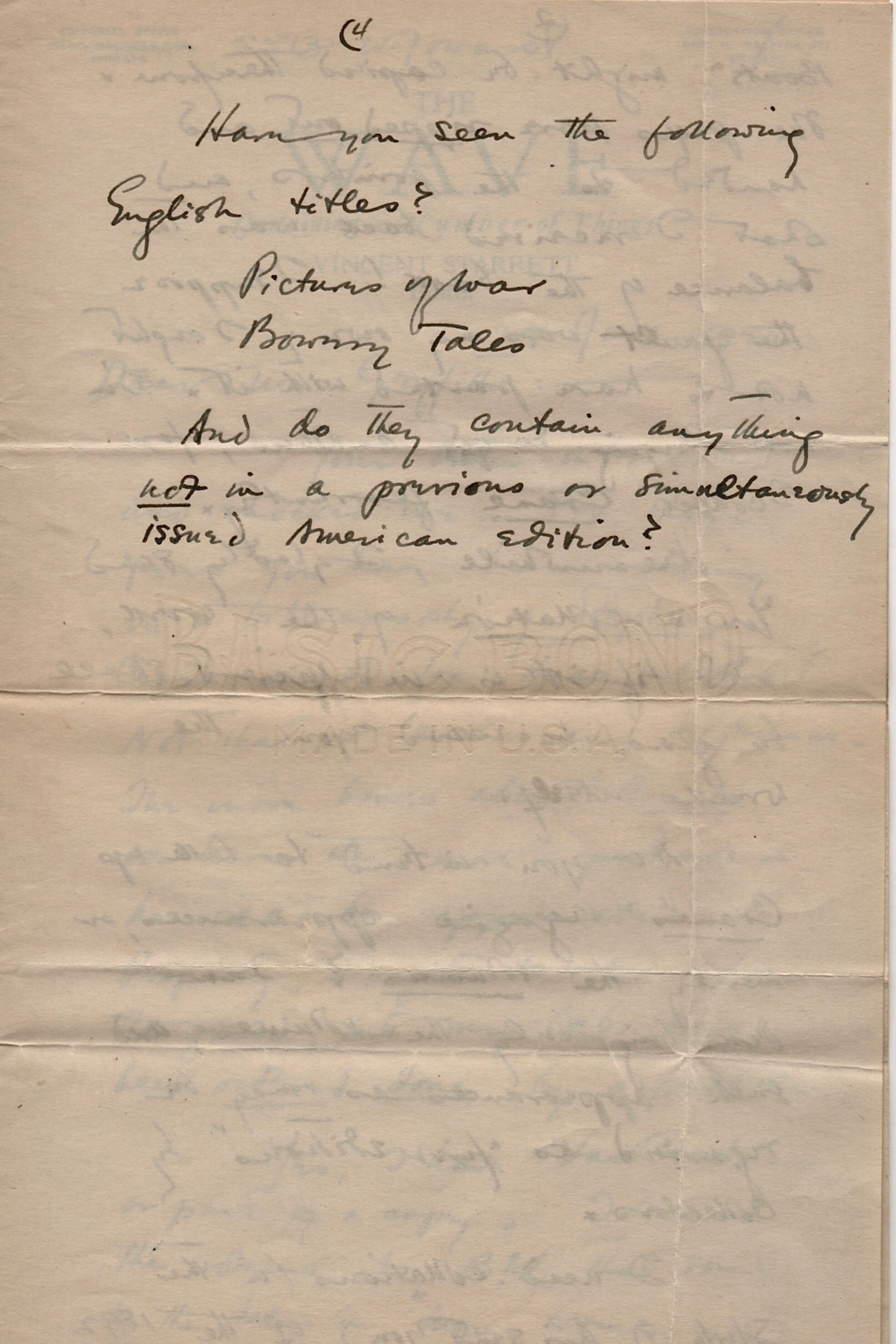

Despite knowing Starrett’s bibliography will come out first, Griffith agrees to answer more than a dozen questions in an October letter to help the Chicago writer identify certain editions. He starts off stiffly:

“To answer the questions in our last two letters as far as I feel justified in doing in view of the fact that I am also writing a bibliography of Crane, and have spent three years in digging up just those points upon which you ask special information—”

After offering brief answers, Griffith asks a question of his own:

“There is one question that I asked you several letters back that I would appreciate your answering: are you planning to get out another volume of the Crane items? If so, will you let me have a list of contents so that we will not conflict?”

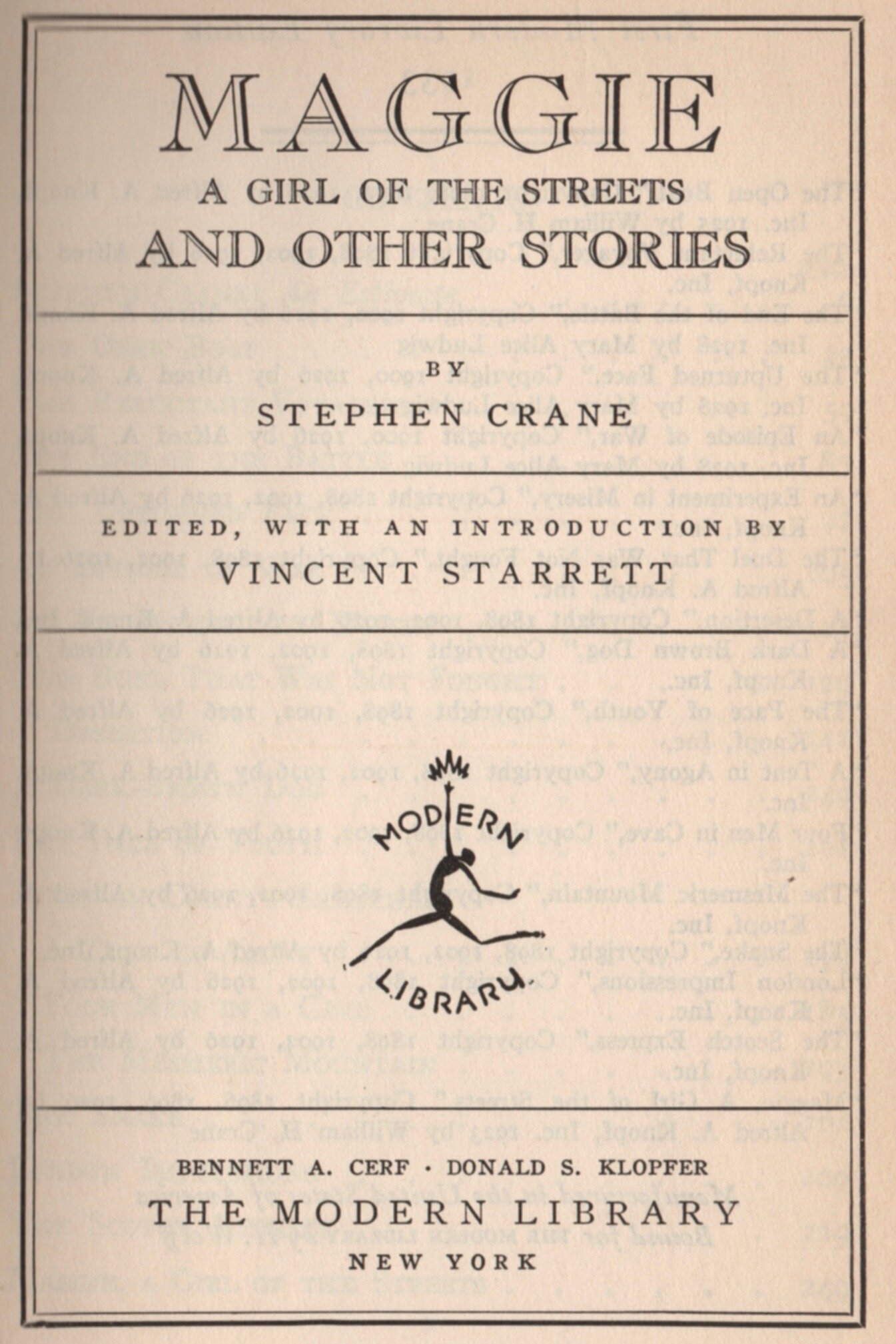

When Griffith mentions “another volume” he is likely referring to a sequel to Men, Women and Boats, a collection of unpublished or obscure Crane short stories gathered and introduced by Starrett for a 1921 Modern Library edition. (Variants of that edition are pictured here.)

It’s possible the Modern Library book helped Starrett sell himself as the man to write a Crane bibliography to Harold Mason. Mason had recently opened what would become an influential establishment named the Centaur Book Shop at 1224 Chancellor Street in Philadelphia, about one mile east of Griffith’s Chestnut Street home.

The handsome end papers to the early Modern Library editions of Men, Women and Boats, edited by Starrett.

Part 6: Mr. Starrett Apologizes. Sort of.

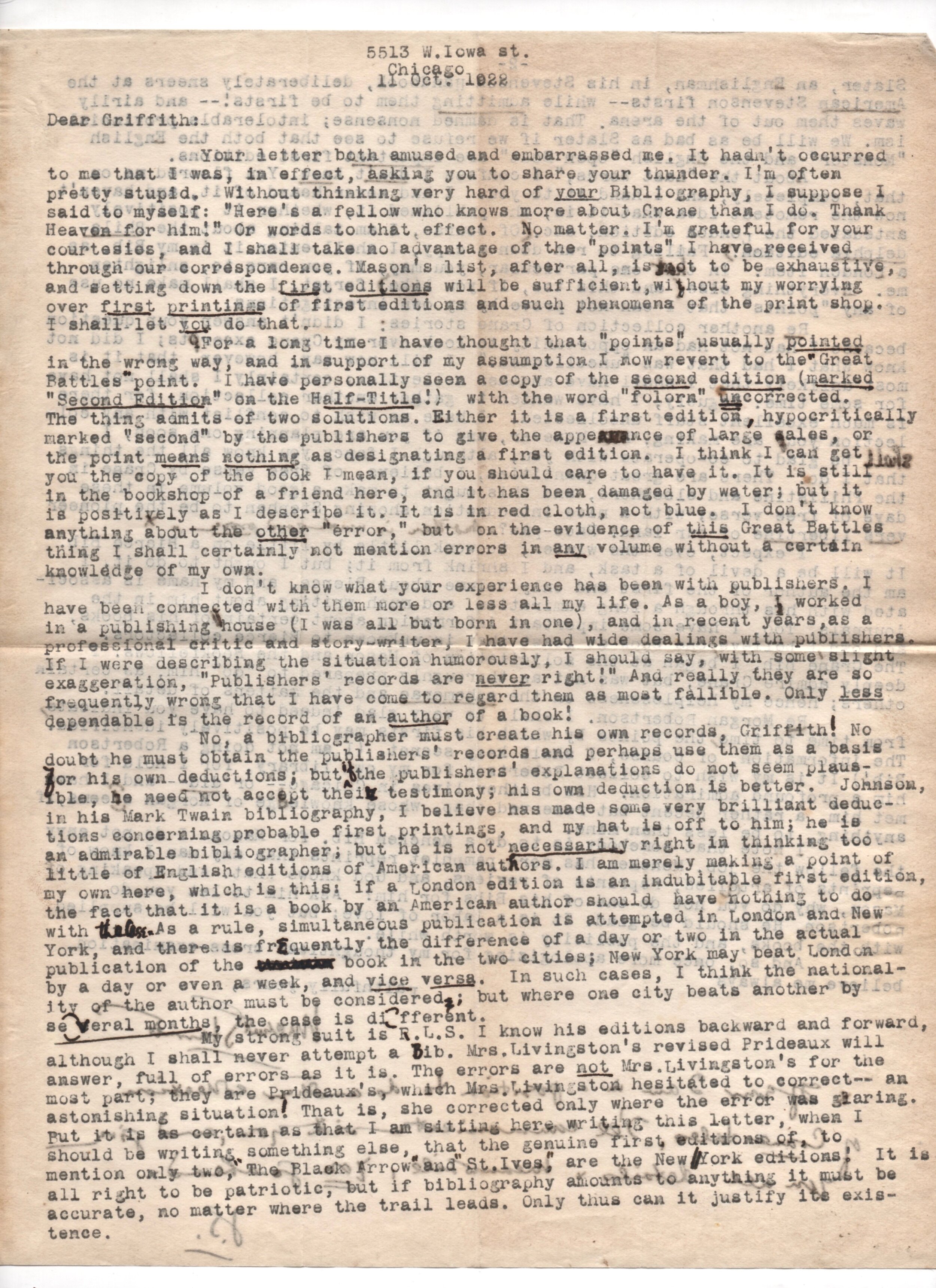

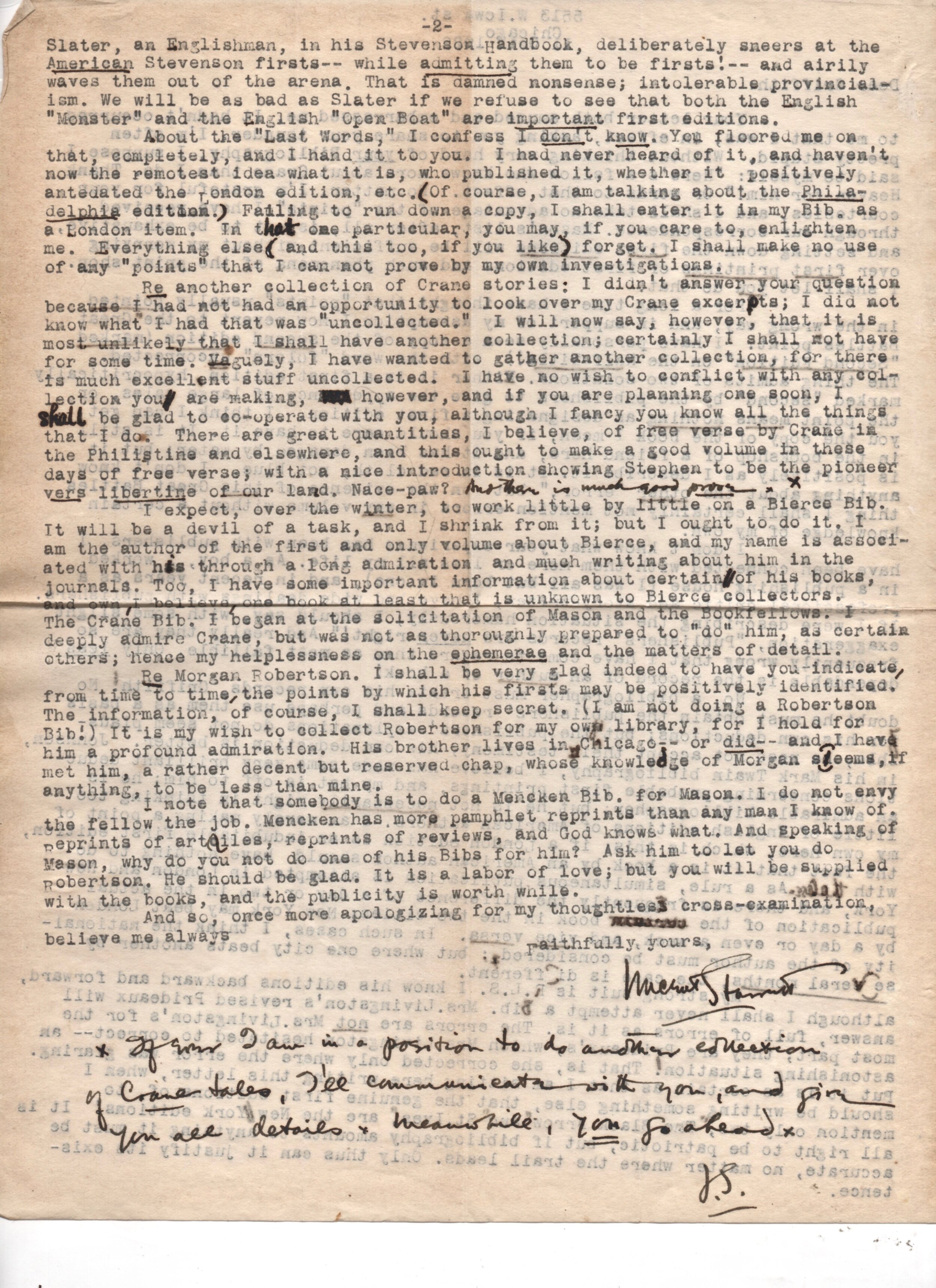

Later in their correspondence, it appears Starret finally realized how upset Griffith was. Here’s how he starts his Oct. 11 letter:

“Your letter both amused and embarrassed me. It hadn’t occurred to me that I was, in effect, asking you to share your thunder. I’m often pretty stupid. Without thinking very hard of your bibliography, I suppose I said to myself: ‘Here’s a fellow who knows more about Crane that I do. Thank Heaven for him!’ Or words to that effect. No matter. I’m grateful for your courtesies and I shall take no advantage of the “points” I have received through our correspondence.”

Really? Did Starrett really say “Thank Heaven for Griffith?” One wonders if Starrett was more relieved that his bibliography already had a publisher, whereas Griffith was still casting about for someone to publish his three-year-long research effort.

After much rumination about the “points” which distinguish first and second editions, British and American printings, and other esoterica, Starrett comes back around to his plans for the future and answers the question Griffith asked about another volume of Crane.

“I expect, over the winter, to work little by little on a Bierce bib(liography). It will be a devil of a task, and I shrink from it; but I ought to do it. I am the author of the first and only volume about Bierce, and my name is associated with his through a long admiration and much writing about him in the journals. Too, I have some important information about certain of his books, and own, I believe, one book at least that is unknown to Bierce collectors. The Crane bib(liography) I began at the solicitation of Mason and the Bookfellows. I deeply admire Crane, but was not as thoroughly prepared to “do” him, as certain others; hence my helplessness on the ephemera and the matters of detail.”

A handwritten note from Starrett to Griffith from Oct. 3, eight days before the lengthy two-page typed letter quoted above. This note is pasted into the front free end paper of Griffith’s copy of Stephen Crane, just below Starrett’s inscription.

And so he goes, wavering between braggadocio and humility and, not incidentally, making sure Griffith knew that Starrett’s book would be out first and preeminent in the field.

“And so, once more apologizing for my thoughtless cross-examination, believe me always

Faithfully yours,

Vincent Starrett

If ever I am in a position to do anther collection of Crane tales, I’ll communicate with you, and give you all details. Meanwhile, you go ahead.”

“Meanwhile, you go ahead.”

Doesn’t that sound a bit condescending? As if Starrett could stop anyone from doing their own research into Crane or publishing the results?

Griffith’s angry notations in Starrett’s book make it clear that the bonhomie Starrett tries to affect at the end of the letter was not mutual.

Part 7: The sad tale ends, at least for Mr. Griffith

The Colophon was an interesting idea for book collectors. Early issues had different printers produce each article in signatures, and then bound by Pynson Printers in New York. The 1931 edition (The Colophon, Part Seven) contains an article by Starrett on Stephen Crane. Here is the handsome first page.

Starrett would go on to do the Bierce bibliography, but no others.

As for Griffith, he seems to have disappeared, as I can find no references to him in Philadelphia, or elsewhere, after 1922.

A 1923 Crane booklet by Thomas L. Raymond published in Newark, N.J., by the Carteret Book Club, says a Crane bibliography by O.L. Griffith was “in preparation.”

But of this I am certain: If Griffith produced a Stephen Crane bibliography or story collection, his efforts have not found their way to Worldcat.org or other databases. It is entirely possible that Starrett’s effort took the wind out of Girffith’s sails. And until we get further information, that’s where we must leave this sad bibliophile.

NOTE: Many thanks to Ann Mosher and the researchers in the Special Collections Research Center of Temple University’s Charles Library for hunting through their city directories for the elusive O.L. Griffith. There was only one listing that seems to be him. It’s for an Oram Griffith at 4929 Chestnut in the city. That’s the same address as Starrett used, so it’s likely that O.L. Griffith = Oram Griffth. Neither name shows up again in public material as far as I’m able to find.

Before we go, here’s the 1933 Modern Library edition of Crane’s Maggie: A Girl of the Streets, edited and introduced by Starrett. Finding a copy with its evocative dust jacket, even one that’s weathered, is not easy.