"Our Correspondent Wounded!"

Was Starrett shot while reporting on the Mexican uprising?

Starrett in the “uniform” he wore while a war correspondent covering the Mexican conflicts in the 1910s.

At last, Vincent Starrett was going to see war action!

After kicking his heels in Chicago chasing down photos of murdered members of the city’s underworld for the Chicago Daily News, Starrett got the chance to go to Mexico to cover an uprising, led in the north by Pancho Villa, against the government of President Victoriano Huerta. The various factions that formed, dissolved and reformed in different configurations baffled most Americans, but Starrett didn’t care. He was finally going to have a chance at being a war correspondent like his hero, Richard Harding Davis.

Many of his reports were reprinted in Peter Ruber’s book, War Correspondent for the Silicon Dispatch Box Press.

Consider Starrett’s report from May 6, 1914, with these stacked headlines:

British Girl Nurses Wounded U.S. Marine

Bluejacket, Shot by “Sniper”

in Vera Cruz Fight, Sinks Down at Her Feet

Held Between Two Fires

Stanches Flow of Blood Until Comrades Take Him to Hospital

Photo Postals Popular

By Charles V.E. Starrett

(Special Correspondent of The Daily News)

Takes away your breath just reading the headline, doesn’t it?

Lets take a closer look at that one subhed: “Photo Postals Popular.” Here’s what he wrote in his dispatch about the topic:

Perhaps the most flourishing business in Vera Cruz these days is the selling of picture postal cards. Not the handsomely lithographed affairs depicting the splendid churches and cathedrals of this old Spanish town but actual photographs of the fighting that was seen in this white street just two weeks ago to-day. Some of the most horrible of the photos show the huddled and silent dead strewn at the street corners and under the portals of the leading hotels.

It is a queer pasttime, this collecting of the gruesome pictures, but the demand is immense and to satisfy the morbid taste of the city shipments of newer and even more horrible photographs from Mexico City recently have been added to the stock for sale.

The callousness of the Latin population is well illustrated in one of the most popular pictures, which shows a smiling boy calmly sweeping the sidewalks before the Hotel Diligencias, while all about lie bodies of slain Mexicans in the grotesque attitudes of men struck suddenly dead.

There is more than a little “callousness” evident here.

Reporters hanging out at the cable office in Vera Cruz.

The Battle of Xochimilco: Version 1

So you get the idea. Now, let’s get to the tale of foolishness in “battle” and how it changed over time. First up is how the story ran in McNaught’s Monthly for June 1927, entitled “The Battle of Xochimilco.” This account also comes from Ruber’s War Correspondent.

The outline is this: American reporters are bored after a long lapse in the action, and Starrett is stuck playing pool with two others at the American Club. Then comes a rumor of skirmishes between federal forces and the guerrilla fighters. The three head for the rumored action.

The lack of transportation found the reporters in a horse-drawn “victoria” carriage, being driven 11 miles out of town over dirt roads. The driver got cold feet and put out the reporters, who had to walk to Xochimilco. They came upon federal soldiers, only to find the rumors were false.

“We who had for weeks been creating rumors of rape and raid, had fallen victims of the first report that was not of our own imagining.”

A hand written caption on back of the photo identifies the two as Starrett on the left with Fred Boalt, a reporter with United Press International or UPI.

Seeing an opportunity for publicity, the lieutenant in charge offers to take the reporters to the colonel at the farthest reach of the army’s wilted might. Hoping to get his photo in the American newspapers, the colonel offers to have his troops fire across one hill into a copse of trees on the other. A simulated battle for the media, if you will. The colonel’s troops fire away with their leader posing for photos.

“Then something happened that was not on the program. Out of a clump of trees on the distant hilltop sprang a little puff of smoke, quickly followed by another, and a bullet hummed into our midst and struck deeply into a tree-trunk.”

When the shooting stopped, two federal soldiers had been killed. Starrett had thrown himself behind a large rock to avoid the gunshots.

The whole episode had lasted, I suppose, about a quarter of an hour, and it was another fifteen minutes before the exchange of courtesies was over and the firing fell off. It ceased as suddenly as it had begun, and cautiously we all crept from our concealment.

The reporters straggled their way to the road.

“It was a long trudge back to the City, but we made it in very good order, and by that time, the sun was going down. On the outskirts, a car picked us up and carried us into the capital. The episode was over.”

Later, Starrett would feel guilty for the whole business, knowing those two soldiers died for the ego of their leader and the desire from an equally ragged band of reporters hoping for a little excitement to write about for their papers back home.

You will notice, by the way, there is no mention of Starrett being wounded.

The Battle of Xochimilco: Version 1A

You can’t say that a single line deserves to be called a version of its own.

In 1944, Starrett had a series of his Jimmie Lavender stories syndicated and published in newspaper like The Philadelphia Inquirer. One of the bios that ran with these stories includes the following sentence:

During 1914-15 he served as war correspondent in Mexico and was wounded in the leg.

Moving on.

The Battle of Xochimilco: Version 2

Published by the Chicago Daily News in 1976, this article is based on a 1964 interview with the man himself.

In 1964, when he was 77 years old, Starrett sat for an interview with his old newspaper, the Chicago Daily News. Ten years later, the newspaper published the story again, to honor Starrett at his death.

Headlined, “They staged the battle for us,” the story covers the major news events Starrett reported on for the Daily News, including his work during the Mexico uprising.

The story Starrett recounted roughly follows the version he told 37 years earlier in McNaught’s Weekly. The two versions veer away from each other as he finished the “battle” scene.

After the two federal troops were killed and the shooting had stopped, Starrett and other reporters head for the cover of the woods.

“Then, a last shot fired by one of the Zapatistas hit me.

I felt a sharp blow on the right side of my behind, as if somebody had struck me with a stone, and I as on my hands and knees. My leg was bleeding, and my first thought was ‘My God, I’ve been shot! What a story for the paper!’

My inglorious wound laid me up for a few days, but it has never bothered me since.”

Starrett was shot? That’s a surprise.

Did he forget about it during the first telling?

Or did he deliberately leave it out for some reason?

The Battle of Xochimilco: Version 3

The 1964 interview was sparked, no doubt, by the publication a few months later of Starrett’s memoirs, Born in a Bookshop. The “battle” of Xochimilco finishes up Chapter XII and reaches its climax on page 144. Once again, Starrett and the others take to the woods, accompanied by their interpreter, De Prida.

“I had turned for an instant to look back, and a moment later found myself on my hands and knees, struggling to rise. De Prida saw me collapse and hurried to my assistance.

When he had got me to my feet with some difficulty, I saw that my leg was bleeding through my trousers and my first thought was, ‘My God! I’ve been shot. What a story for the paper!’ I had been shot in the right thigh by a spent ball. …

And that is the true story of my inglorious wound about which I still occasionally brag. I received it while endeavoring to escape from a situation I had myself helped to bring about. It laid me up for a few days but has not troubled me since.”

As you can see, the story roughly follows the McNaught’s and Daily News versions, but with some additional details.

And is it just me, or does his being wounded, and the help of an aide to get him to safety, have echoes of Watson’s wounding in Afghanistan and the help of his trusty aide, Murray. Just a thought.

We are not done.

The Battle of Xochimilco: Version 4

The beginning of Bob Mangler’s tribute to Vincent Starrett.

In May 2001, Robert Mangler, BSI, wrote an appreciation of Starrett for the Caxtonian, the newsletter of the Caxton Society, a Chicago institution founded in the magical year of 1895 to promote books and those who love them. Starrett appointed Mangler his successor at The Hounds of the Baskerville (sic) in Chicago and Bob idolized Starrett.

The tribute Mangler wrote is a brief history of Starrett’s life and includes a paragraph dedicated to his war correspondent role in Mexico.

“In 1916, he was sent to cover the war against Pancho Villa in Mexico. As a war correspondent, he spent much of the time in the Cantina with Jack London and Richard Harding Davis. Since things were too quiet, they paid some of the soldiers to stage a battle. There was one casualty at the battle of Xochimilco — Starrett was hit by a stray bullet in the leg. ‘OUR CORRESPONDENT WOUNDED!!’ the headlines screamed.”

It’s a clear tribute to Starrett, but is it true? Some details (such as the killing of two federal soldiers) have been excised to make Starrett the only victim of the conflict. And did the reporters pay the soldiers to put on their pretend battle? If so, Starrett left that out of his own versions.

The relevant paragraph from Bob Mangler’s appreciation for his old friend Starrett.

And where is the Daily News story with the headline screaming “OUR CORRESPONDENT WOUNDED!!”? Certainly such a clipping doesn’t exist in the material his family has given me, nor is it pasted into the book of clippings that Starrett kept for many years. (The Daily News is not online anywhere that I can see. If you have a copy, or know where I can find one, please let me know. I would love to supplement Manger’s story with the newspaper account.)

All I can say for certain is that Bob Mangler, who became a friend, was adamant about the details in his account, as I learned a few years later.

While putting together the 75th anniversary edition of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, I asked Bob if he would update his essay to become the book’s preface. Bob readily agreed and, with the permission of the Caxton Club, we went about making some changes. I got Bob to correct the date of the uprising from 1916 to 1914, but when I asked about the wounding, Bob was firm. “Starrett told me it happened, so it happened,” he told me emphatically.

And so the anecdote is included in the book, adding yet another version of the tale.

What’s the truth? I’m not sure. I’m hoping this post will spark additional information and if anything new arises, you’ll know.

Postcards from the ‘Front’

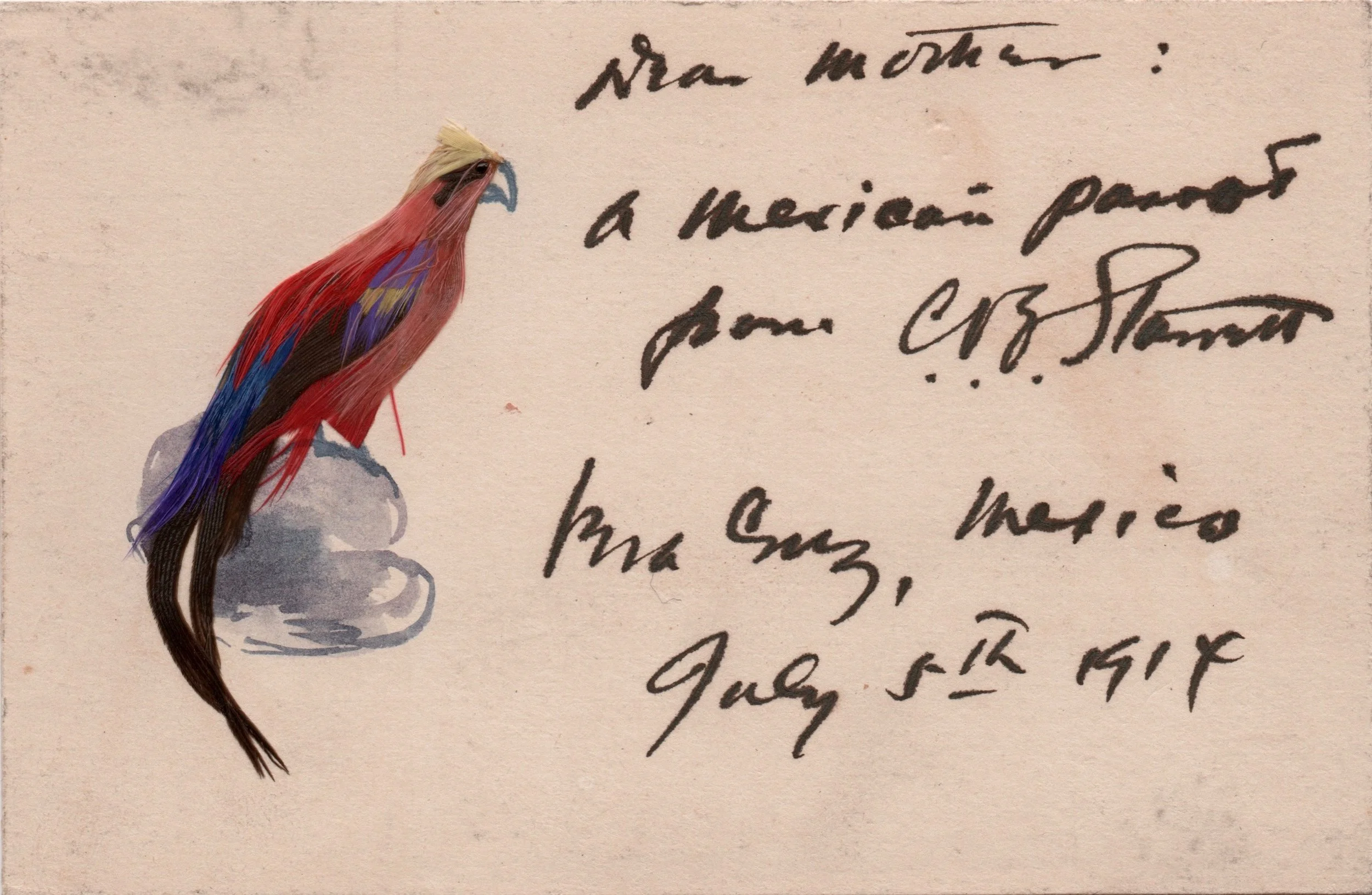

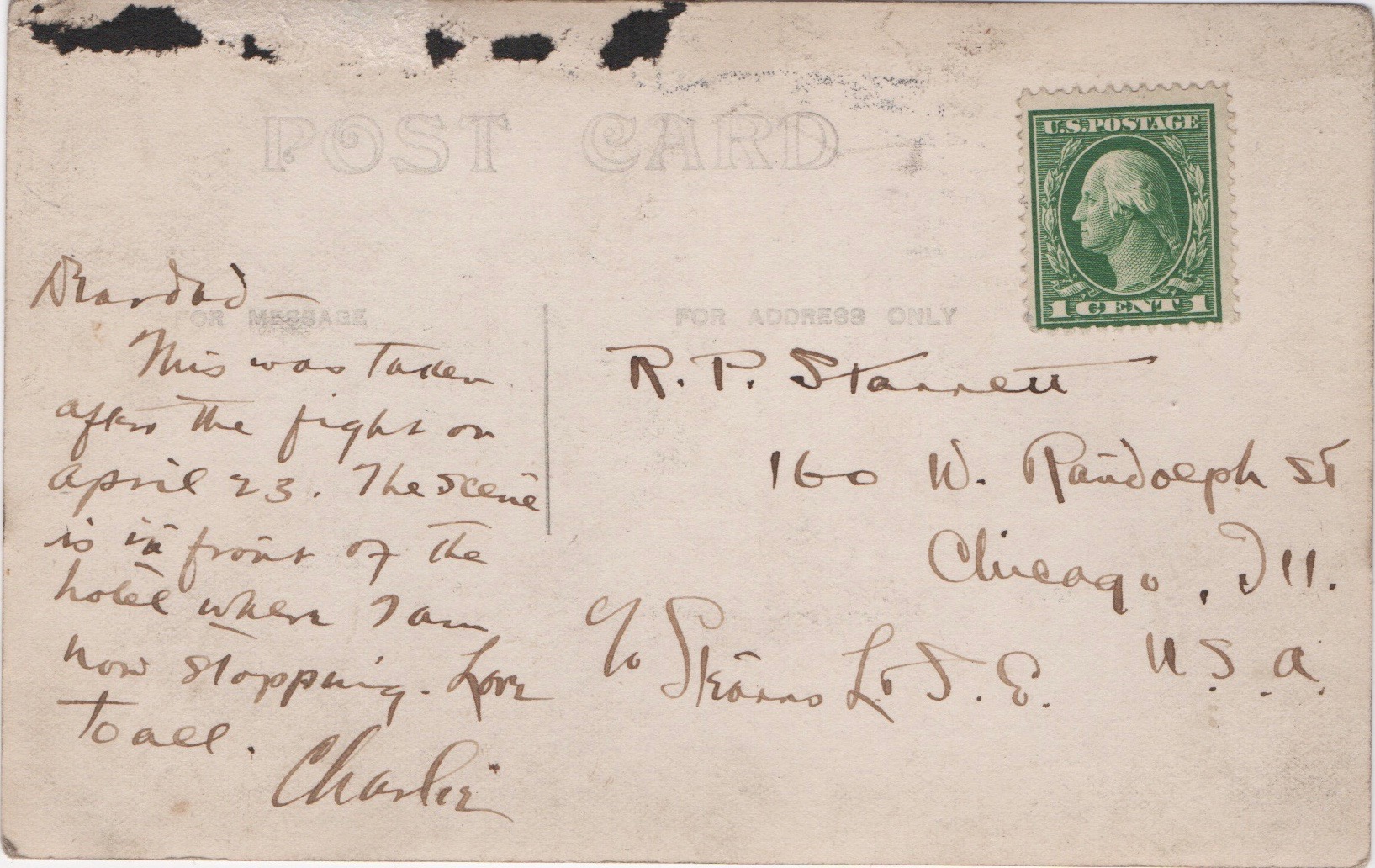

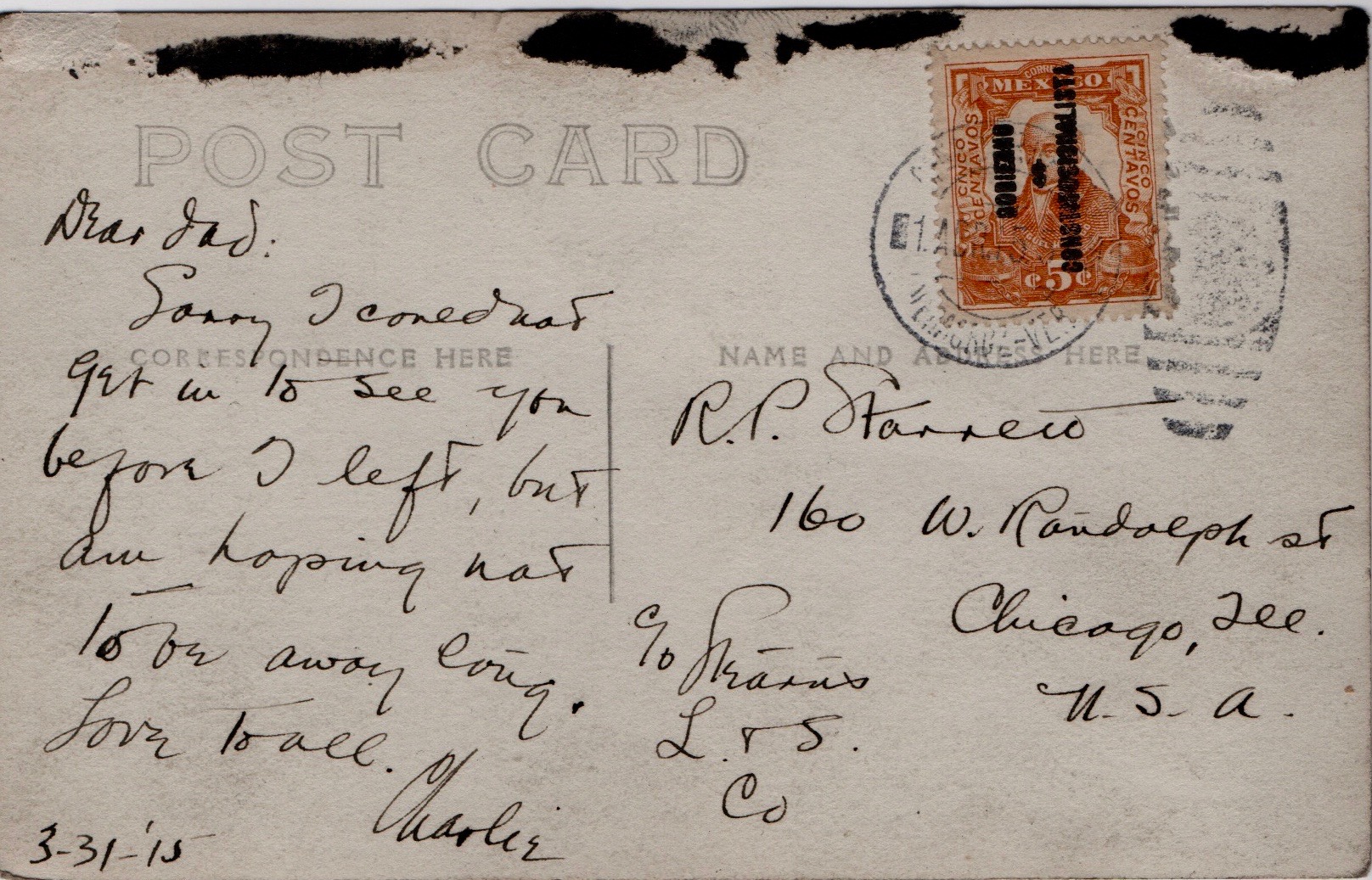

I know this post has been long, but I can’t drop the topic without letting you see a few of the other postcards Starrett sent back from Mexico. Along with images of warships and troops on the move, Starrett bought cards from a local artist who used real bird feathers and a little watercolor to make beautiful images. Even now, more than 100 years later, the colors are as brilliant and playful as they were when Starrett sent them to his family in Chicago.

A few words about the cards. Notice that his note to his mother is straightforward (“A Mexican parrot from C.V.E. Starrett”) while the one to his father is more playful (“I shot this specimen myself, and had it stuffed. I don’t know what it is.”). That reflects the personalities of his parents, with his serious, ultra-religious mother and more happy-go-lucky father. Oh, and the bird on his father’s card looks like a pheasant.

The photo of Starrett on a horse is meant to comical, since, as he says in his note to his brother, “Two minutes after this was taken, the pony ran away with me!”

A final note. You’ll see these cards with the birds are signed rather formally, C.V.E. Starrett. That was the name he was using as a journalist and the name that most of his war dispatches bore when published in the Daily News.

When he was being less formal, he simply signed the cards with the name his family knew him by, “Charlie.”

Finally, I must thank the Starrett family for the album of photographs and newspaper clippings they gave me. Many of the images you see here have never been published before and help illustrate the tale of Starrett’s war reporting very effectively.