'Here dwell together still two men of note'

Chapter 4: The poet creates a masterpiece

‘Put Some Guts into It.’

The poem as typed by Starrett and used in the manuscript for his 1943 book of poetry, Autolycus In Limbo. More about that book later. From the author’s collection.

1942 was not an optimistic time in the world.

In addition to the war in Europe, the growing battles in the Pacific made this a truly World War. And while the worst of the bombing was over for London as Hitler turned his attention to the Soviet Union, the deprivations of war were keenly felt. The United Kingdom instituted rationing of electricity, coal, and gas in February 1942; homelessness was an increasingly common problem.

As one London resident would later recall, “Survival itself was a kind of victory.”

An ocean away, Americans were starting to feel the impact too, as a great national debate was waged over our involvement in the war, fueled by the attacks on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

For Starrett, the devastating war stirred feelings he rarely allowed to surface in his writing.

Carl Sandberg once wrote to Starrett about his poetry and urged his fellow Chicagoan to “put some guts into it.”

Sitting down to write, Starrett held nothing back and put his full heart and mind into a sonnet. He reached back to his thoughts published almost a decade before in The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, and blended them with his hopes for the future of England and the civilized world.

The result was no mere child’s fantasy of adventure, but a series of images that used the Holmesian world to express a deep love for a way of life that was being reduced to ash.

221B

(for Edgar W. Smith)Here dwell together still two men of note

Who never lived and so can never die:

How very near they seem, yet how remote

That age before the world went all awry.

But still the game’s afoot for those with ears

Attuned to catch the distant view-halloo:

England is England yet, for all our fears –

Only those things the heart believes are true.A yellow fog swirls past the window-pane

As night descends upon this fabled street:

A lonely hansom splashes through the rain,

The ghostly gas lamps fail at twenty feet.

Here, though the world explode, these two survive,

And it is always eighteen ninety-five.[March, 1942]

Now that you’ve seen how it looks as Starrett typed it, let us see if we can’t get just a little closer to how he “heard” it in his head as he was writing it.

The best way is to hear him read it aloud. In 2012, Wessex Press created a CD called “Starrett Speaks: The Lost Recordings.” Although out of print today, it is possible, with the gracious blessing of the publisher, to offer you this recording, made somewhere around 1970, in the last years of Starrett’s life.

There may be other recordings of Starrett reading his most famous sonnet, and if you have one and would be willing to share, let me know. I would love to add them here.

‘Herewith a Sonnet About the Great Companions’

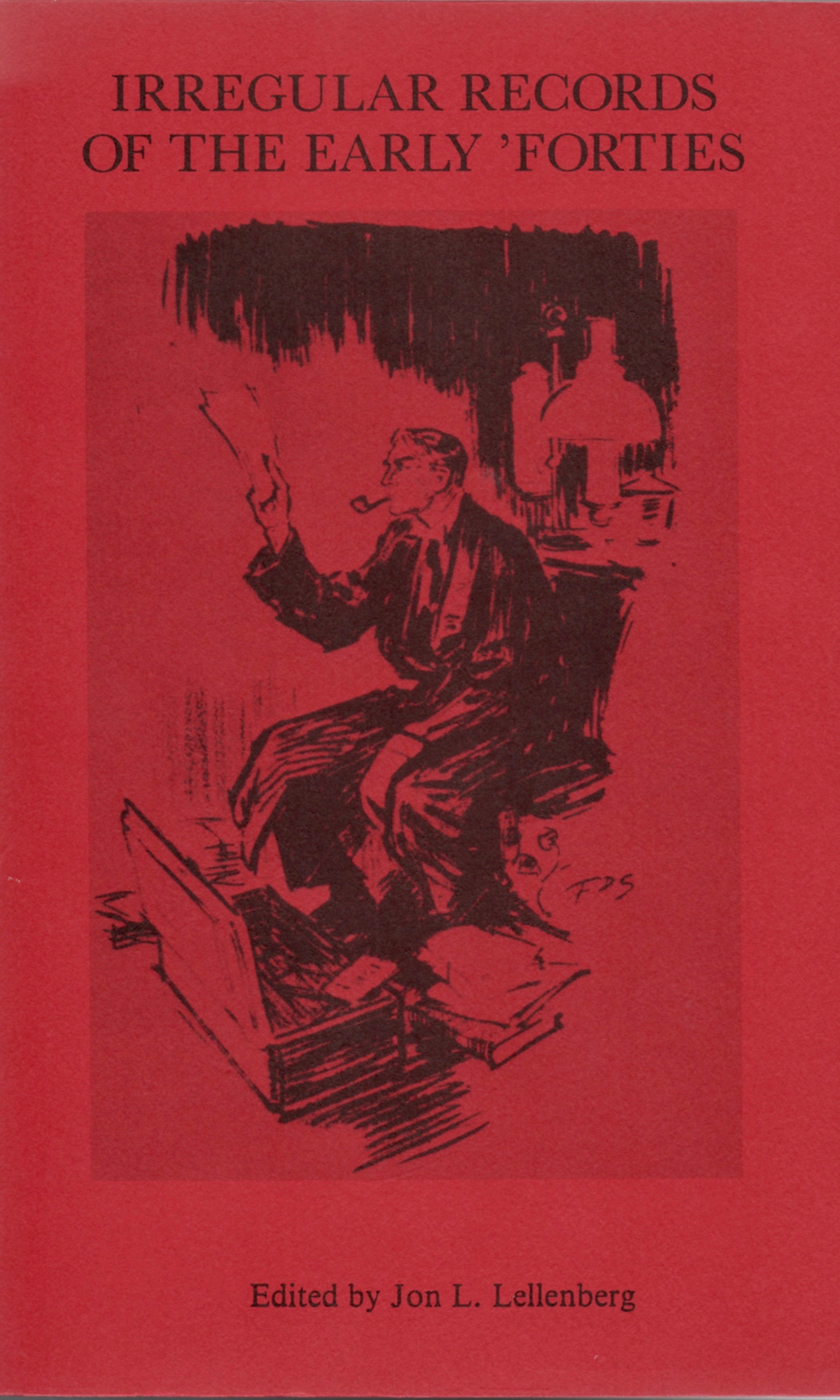

According to the events chronicled in Irregular Records of the Early ‘Forties (published in 1991 by Fordham University Press for the Baker Street Irregulars), here’s how the poem began its private life.

Not long after it was written, Starrett sent a copy to Edgar W. Smith, who had become the secretary or Buttons of The Baker Street Irregulars. Several years before, Smith had contacted Starrett after reading The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Smith was delighted by the book, but took issue with some of Starrett’s Sherlockian observations. Even so, the two men became brothers in Holmes from that point on.

The fact that Starrett dedicated his sonnet to Smith is both unusual and significant. Starrett rarely included a dedication in his poetry, but he did so now, I believe, as a sign of deep respect. In later years, whenever Starrett oversaw a reproduction of the sonnet, the dedication was always there.

The reason for the dedication is made clear in a March 30 cover letter Starrett sent to Smith along with the a copy of the new sonnet. In his cover letter, Starrett wrote:

Herewith a sonnet about the Great Companions, which I hope may be part of a slim volume this autumn. Since the second line boldly appropriates one of your best lines, the least the poet can do is dedicate the stanzas to you – but, indeed, he wanted to anyway.

Smith was honored by Starrett’s gesture. In writing back, Smith made a significant observation, one that illustrates his intellectual acuity.

It is not the second line of the sonnet I like best, (Smith wrote) even though you attribute the inspiration for it to me; it is the eighth line, which says, so very believingly, and therefore so very truly:

“Only those things the heart believes are true.”

(One note before we close. You may have noticed that in his cover letter to Smith, Starrett mentions a “slim volume” to be published in the autumn. That volume was a collection of poetry published in 1943 by E .P. Dutton & Co. which he called Autolycus in Limbo. I own the manuscript of that book and that is where the typewritten page of “221B” seen above comes from.)

Having had its private unveiling, “221B” was now ready for its public life, as we will explore in Chapter 5.

‘221B’ Chapter Index

Chapter 1: Introduction and Prologue: ‘Where it is always 1895’

Chapter 2: 'So they still live for all that love them well'

Chapter 3: ‘Some of the most dramatic months… of contemporary history’

Chapter 4: ‘Here dwell together still’

Chapter 5: ‘He has done many little things for me’

Chapter 6: ‘A wider circulation’

Chapter 7: ‘Part of a slim volume’

Chapter 8: ‘This poem by my good friend’

Chapter 9: ‘Something remains of London in 1895’

Chapter 10: What is it we love about ‘221B’?

Chapter 11: Afterthoughts and Acknowledgments

Want to chat about this blogpost? Join us at the Studies in Starrett Facebook page: