A classic is born

Private Life Chapter 3: First American Edition

The dust jacket cover to the American first edition of Private Life. Holmes is easy to pick out, but can you name the others?

The dj spine.

When Macmillan published The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes in October 1933, there was nothing else quite like it in the United States.

There were many compilations of the Sherlock Holmes stories available, but in the U.S. no one had thought of putting out a book about Sherlock Holmes as an independent phenomenon. Starrett deserves credit for the idea and for the execution of a work that would help create an international recognition of Holmes’ singular role as the pre-eminent private detective.

Which is not to say the title was unique. There had been Private Life books about historic characters like Tutankhamen, Louis the XV and Charles the Second. Perhaps the most famous was John Erskine’s 1925 best seller, The Private Life of Helen of Troy, a novel that looks at what Helen’s life was like after the fall of Troy. Humorous and frank, it imagined Helen, not as a wicked seductress, but a beautiful woman caught up in dangerous circumstances and whose love of life allows her to evade social convention.

Maybe that was the book some folks were hoping to read when they picked up Starrett’s Private Life. If so, they would be surprised.

The book spine

While a few of his essays fill in the gaps of what life was like in Baker Street when Holmes and Watson were not untangling mysteries, Starrett never intended to write a novel. He had no interest in creating new back stories or lost loves for the great detective. No, he was fascinated by two major themes: What life at 221B might have been like had Holmes been real, and how the character was born, developed, shaped by artists and actors, and became something more than a work of the imagination.

Starrett’s intended audience were imaginative readers just like him: the grown-up boys and girls who had devoured the Holmes stories as children and didn’t want the thrill of the adventure to fade, just because Arthur Conan Doyle had died three years before.

Why, Starrett seems to ask, must the game end?

As I’ve said elsewhere, it was the genius of Starrett’s Private Life that he showed adults how to play with Sherlock Holmes in a way that was child-like, but not child-ish.

It would also lay out some of the common strands of commentary we continue to explore more than 85 years later.

The American First Edition: A Description

The Macmillan Company, New York, October 1933. First Edition. Hardcover. 7 7/8" X 5 5/8". viii, [vi], 214pp.

Cover: Deep navy blue cloth over boards. THE PRIVATE LIFE OF/SHERLOCK HOLMES/VINCENT STARRETT in gilt, with a stamped woodcut of Frederic Dorr Steele’s drawing of William Gillette as Holmes.

Spine: THE/PRIVATE LIFE/OF/SHERLOCK/HOLMES; Line; STARRETT at head. MACMILLAN at tail.

Blue topstain to pages.

Reprinted: January 1934

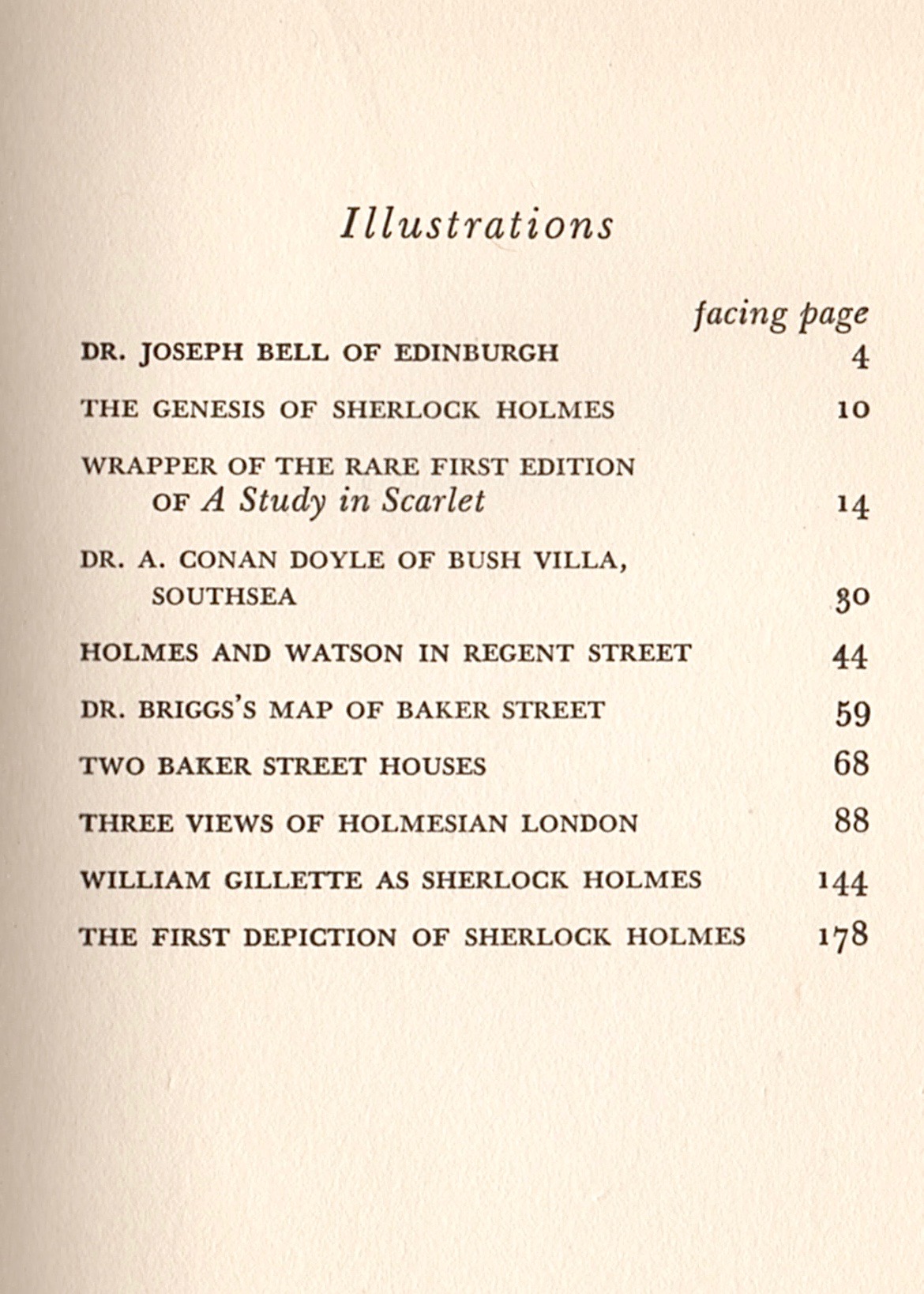

Dust Jacket: THE PRIVATE LIFE OF/SHERLOCK HOLMES at top of cover; By VINCENT STARRETT at bottom. Lettering in red on a tan background with most of the page taken up by D.H. Friston’s frontispiece from the first edition of A Study in Scarlet. The same image is published opposite page 179.

Spine: THE/PRIVATE/LIFE/OF/SHERLOCK/HOLMES; STARRETT at head. MACMILLAN at tail.

Back cover: “Macmillan Fall Biography” with THE PRIVATE LIFE OF SHERLOCK HOLMES by Vincent Starrett listed as the first item.

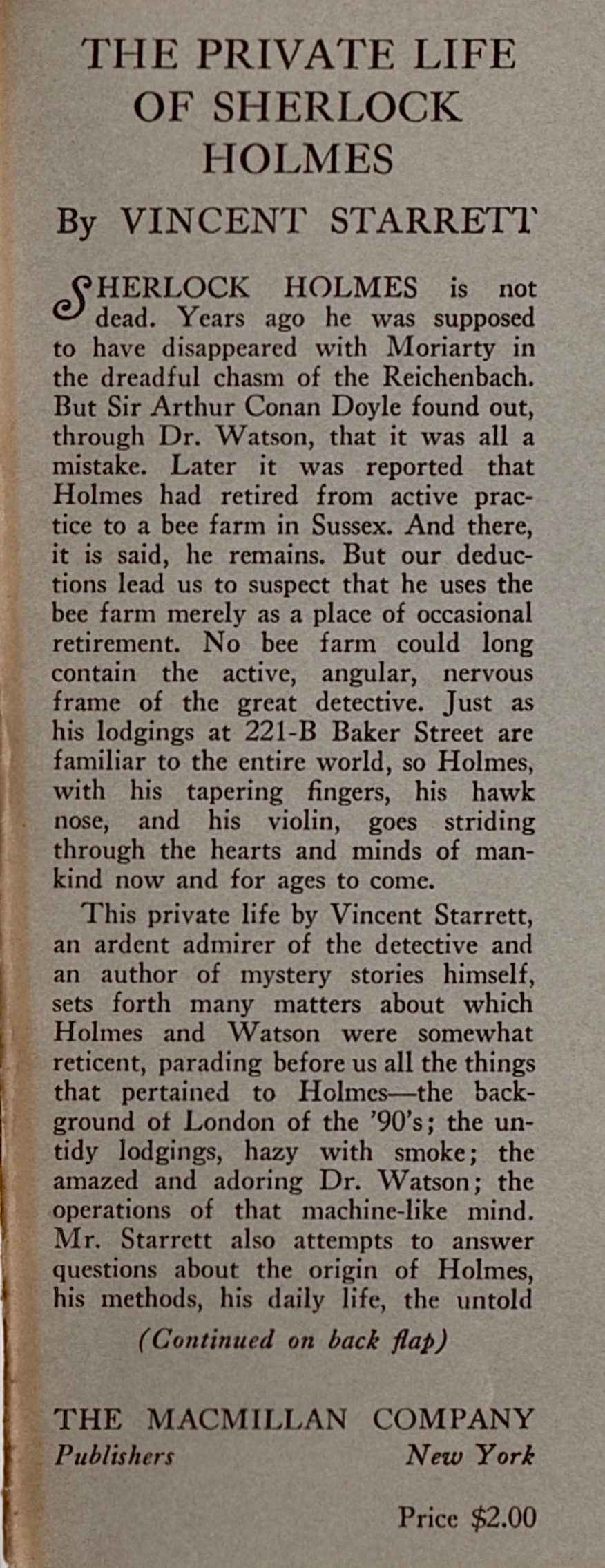

Front inside flap: THE PRIVATE LIFE/OF SHERLOCK/HOLMES by Vincent Starrett. Blurb describing the book, continued on back flap. Price $2.00

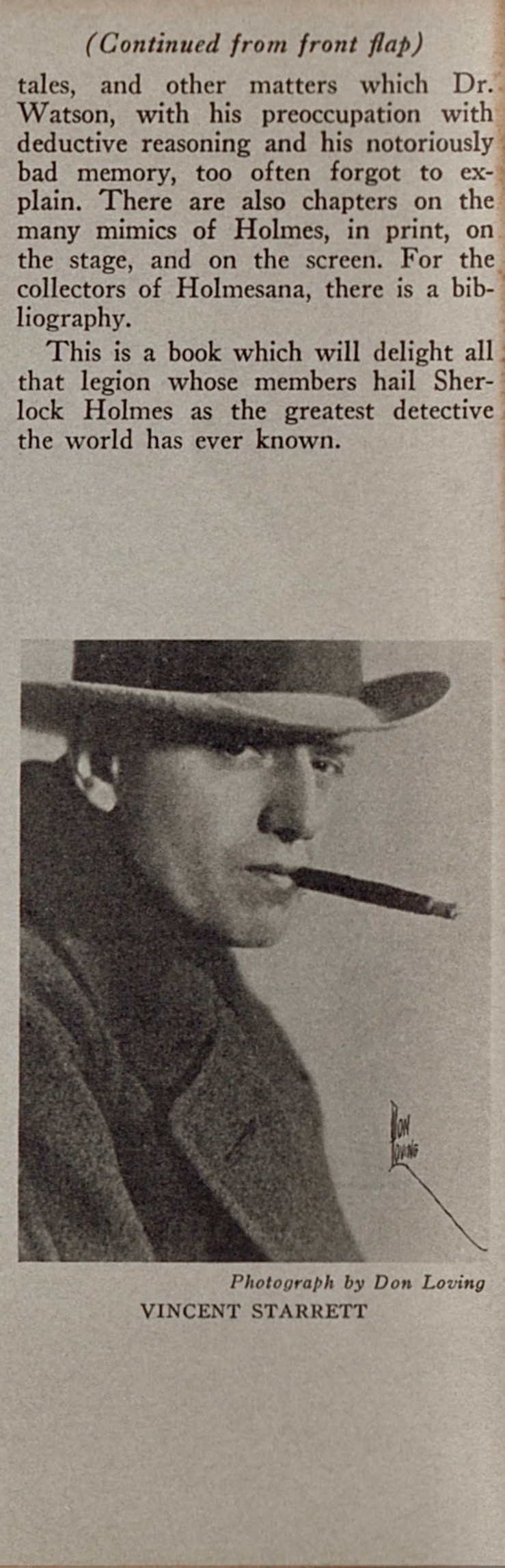

Back inside flap: Continued blurb and a photograph of the author by Don Loving.

Dedication: “To/William Gillette/Frederic Dorr Steele/And/Gray Chandler Briggs/In Gratitude”

Price: $2.00

Thoughts on the first edition

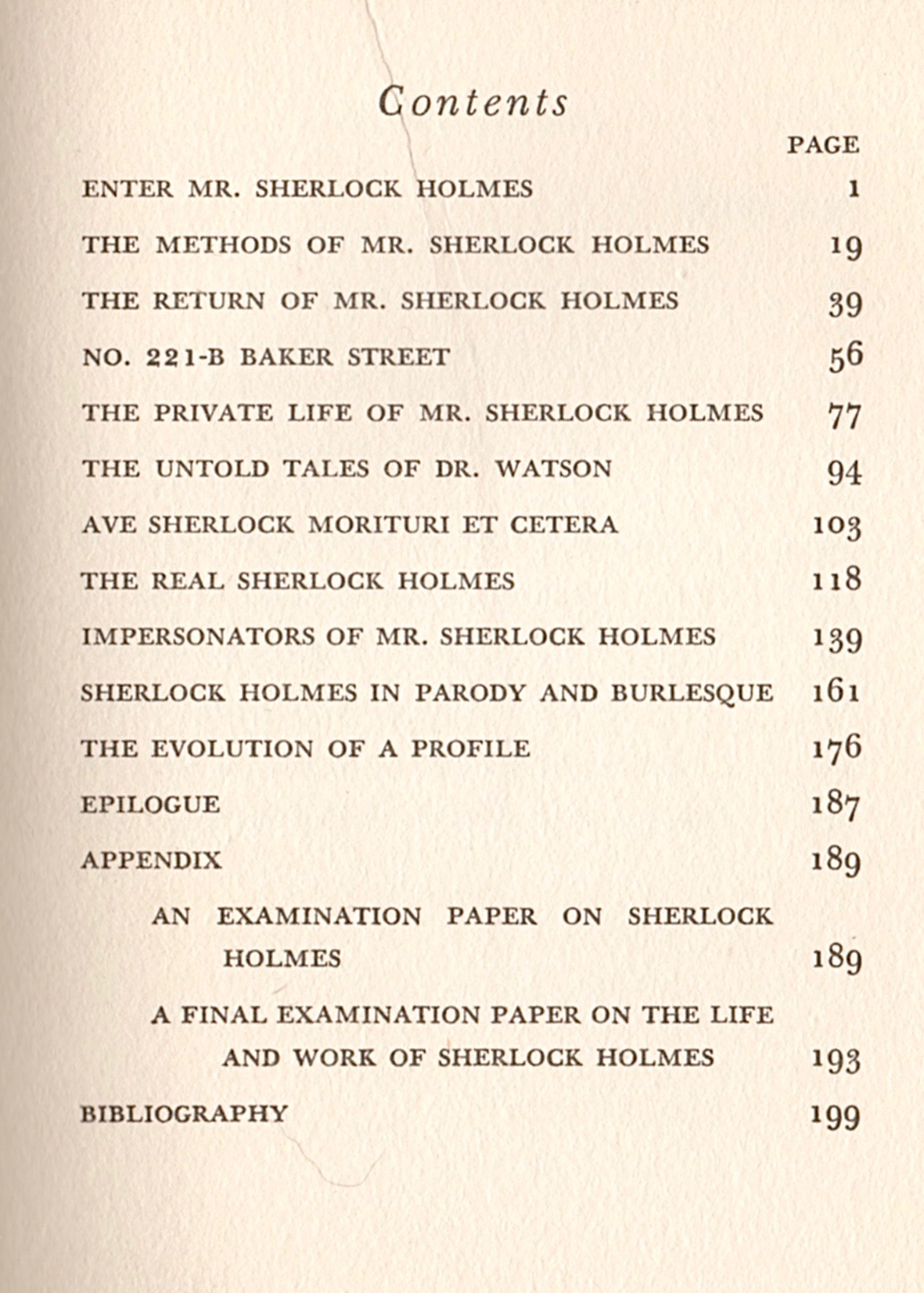

Starrett sets out some of the major lines of what we now recognize as Canonical criticism. For example, whole books have since been dedicated to the films, radio and TV shows featuring Holmes. Starrett provides a concise report up to 1933 with “Impersonators of Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” the book’s 9th chapter.

Those who enjoy parodies and pastiches would do well to try, “Sherlock Holmes in Parody and Burlesque,” the 10th chapter.

And for all who are fascinated by how our image of Holmes has changed over time, there is “The Evolution of a Profile.”

Couple this with chapters on linking historic sites in London with those in the Canon and a detailed listing of Dr. Watson’s untold tales, and you can see the main themes that make up any issue of The Baker Street Journal.

Anyone expecting explosive revelations (like Rex Stout’s “Watson was a Woman”) or similar work will be disappointed. Starrett was content to trace the gentle ripples and waves that flow through the 60 original stories, leaving a pleasant feeling of having spent time with old friends. He was not interested in tossing grenades.

Private Life was based on Starrett’s collection of books, newspaper and magazine clippings. Indeed, his last chapter was the first major bibliography of Sherlock Holmes to be published in book form, and it was largely taken from pulling works off his shelf or out of various file folders. For decades, other collectors (including Edgar W. Smith) would use Starrett’s biography as a guide in their own book hunting.

Do you enjoy scion society quizzes? There are two "examination papers" reprinted here, one by Desmond McCarthy, the other by E.V. Knox.

Starrett also offered a number of illustrations, especially those which were relatively unknown in 1933. The dust jacket cover, for example, is D.H. Friston’s work showing Holmes, Watson, Gregson and Lestrade from A Study in Scarlet. The illustration was also used opposite page 178. Familiar today, it was hard to find in 1933, as was the notebook page with “Sherrinford Holmes” and “Ormond Sacker,” Conan Doyle’s original names for our heroes. Add to this the photos of Baker Street and a reproduction of the Beeton’s Christmas Annual cover and you have an impressive gallery of images.

See that photo by Dan Loving at the bottom of the dust jacket back flap? It’s one of the most famous photos of Starrett ever published. You can learn more about it here.

A bookmark echoing Starrett's homage to Baker Street. I don’t know the name of the artist whose initials are JVW.

For my money though, the most memorable contributions are Starrett’s turns to prose poetry. His sheer love for the subject came through time and again, that child-like faith that if you squint just a bit, you can see Moriarty sitting in the center of his web, Mrs. Hudson treading up the 17 stairs, and Wiggins racing into the fog, while Holmes and Watson dash out the front door of 221B and into a waiting hansom cab.

I know I quoted his words last time, but I’m going to do it again:

“But there can be no grave for Sherlock Holmes or Watson. … Shall they not always live in Baker Street? Are they not here this instant, as one writes? … Outside, the hansoms rattle through the rain, and Moriarty plans his latest devilry. Within, the sea-coal flames upon the hearth, and Holmes and Watson take their well-won ease. … So they still live for all that love them well: in a romantic chamber of the heart: in a nostalgic country of the mind: where it is always 1895.”

Whole books have been written about Holmes and never had one paragraph that reach this lyrical level. Perhaps it’s too much to expect for us. But this is Starrett at his most talented and, I believe, one reason why this book continues to resonate today.

Many reviewers agreed.