The 1960 edition among the critics

Private Life Chapter 9: Will They Still Love Me?

The Chicago Tribune published an excerpted chapter in the Sunday, May 15, 1960 edition on page 24.

In 1933, most American book critics were charmed by the idea that an adult would think about Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson and their home in 221B was real enough to deserve a series of chapters devoted to their lives.

The first edition of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was a hit and as groups of devotees began gathering in American cities, the book became a cornerstone work. By 1960, first and second generation Sherlockians thought of it as a classic.

Tinkering with a classic is rarely a good thing.

Readers tend to be devoted to their first loves, and when you change the object of their devotion, you are likely to invite a nasty reaction. (Film lovers are much the same. Just ask George Lucas, who “Improved” his three Star Wars films for their re-release and suffered the wrath of fans who wanted their clunky special effects and original Ewok celebration music.)

So if Starrett was a little nervous that the revised second edition of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes was going to be skewered for NOT being the first edition, you could understand why.

Fortunately, Starrett had little worry about. While some complained of a favorite chapter or other item being lost in the revision, the affection for the first book, and the admiration many had for Starrett himself, ensured there would be gentle and upbeat reviews.

For example, you would expect The Chicago Tribune to promote the work of one of its most prominent book critics and you would be right. The Tribune published an excerpted chapter of the book on May 15, 1960. It was a portion of the book’s first chapter, “Enter Mr. Sherlock Holmes.” which had largely gone untouched since it’s publication in the first edition in 1933.

The photo accompanying the excerpt (known in the business as a headshot or, at some papers hedshot) shows Starrett at 74. His hair was completely white and starting to recede. The thick glasses were needed to make up for Starrett’s fading eyesight.

Nevertheless, he remained a handsome man and his visage was still iconic in the Tribune and in bookish circles around the city.

The ‘Linemaster’ speaks

The Tribune also called in a ringer to review the book on May 1, none other than Charles Collins, who for many years ran the Tribune’s “Line O’Type or Two” column as its “linemaster.” Collins, you might recall, was one of the four founding fathers of the Hounds of the Baskerville (sic), Chicago’s oldest Sherlockian group. Starrett was another of the founding four. Starrett also credits Collins for getting him a job at the Tribune writing about books. So the two were tight.

Collins’ review reads more like a press release. I’m going to quote it in full. It’s only four paragraphs long.

A late-in-life photo of Chicago Tribune columnist and Starrett friend Charles Collins, left. Not sure who the fellow on the right is.

Sherlock Holmes Myth Retold in Graceful Prose

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes by Vincent Starrett [University of Chicago Press, 156 pages, $4.75].

Reviewed by Charles Collins

Here is a piece of treasure trove for anyone who is acquainted with the Sherlock Holmes saga as recorded by his associate, Dr. John H. Watson, and publicized by A. Conan Doyle, eminent novelist. Since the hero still enjoys international fame, the book should appeal to millions of readers. The number of those who might object to it because they prefer more modern sleuths—Peter Wimsey, Hercule Poirot, Maigret, and the multitude of others—may be safely estimated at zero.

Written by Vincent Starrett, a high priest of the Holmesian cult, this is a revised version of a work published 27 years ago and now a costly item for collectors. The contents of the earlier book have been substantially rewritten. The revision was purely stylistic and the myth has been retold in a vein of lucid, graceful prose which will delight the faithful and also charm the unbelievers. Moreover, Starrett has added a chapter of his own invention, in which Holmes solves a crime which satirically involved collectors of first editions.

The volume is right with enlightenment on every aspect of the lore of Holmes and the period in which he flourished as the world’s only consulting detective. The author’s scholarship in Holmesiana is supreme, and he writes as if communicating a happy sense of enchantment. He says in an epilog (sic):

“Surely for armies of readers the most interesting street in the world is London’s Baker Street, forever the address of Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson. … A street of ghosts, if you will; but if there is any person who questions the reality of these wraiths, let him write to the Central Post office, London, and ask how many letters have been received in the last half-century addressed to Mr. Sherlock Holmes, 221B Baker Street—a man who (cynics will tell you) never lived and a house that never existed.”

The format is a masterpiece of decorative design.

Well now. You can’t get any more adulatory than that, can you?

‘The two editions complement each other’

Collins was not alone in his praise.

James Buchholtz, a reporter for the tiny newspaper in Delphos, Ohio (about 2 hour’s drive northwest of Columbus) wrote an extended review that included his experience sitting next to Starrett at a Sherlockian gathering in Chicago. Buchholtz got “to marvel anew at his wealth of anecdotes, his remarkable sense of humor, his adroit satire that is witty without being cutting, his infinite tolerance and perhaps, above all, his superb command of the English language.” He called Starrett, “the world’s final authority on all matters pertaining to Sherlock Holmes.”

In his review, Buccholtz praises the addition of Starrett’s pastiche “The Adventure of the Unique Hamlet” in the 1960 edition and then gently notes:

“There is however, an enthusiasm in the earlier edition that is not to be denied. Actually the two editions complement each other, and the true Sherlockian will not rest until he has both on his shelves.”

By the way, Buchholtz was invested as a member of the Baker Street Irregulars in that same year as “James Stanger of The Herald.”

Vincent Starrett, meet Michael Harrison

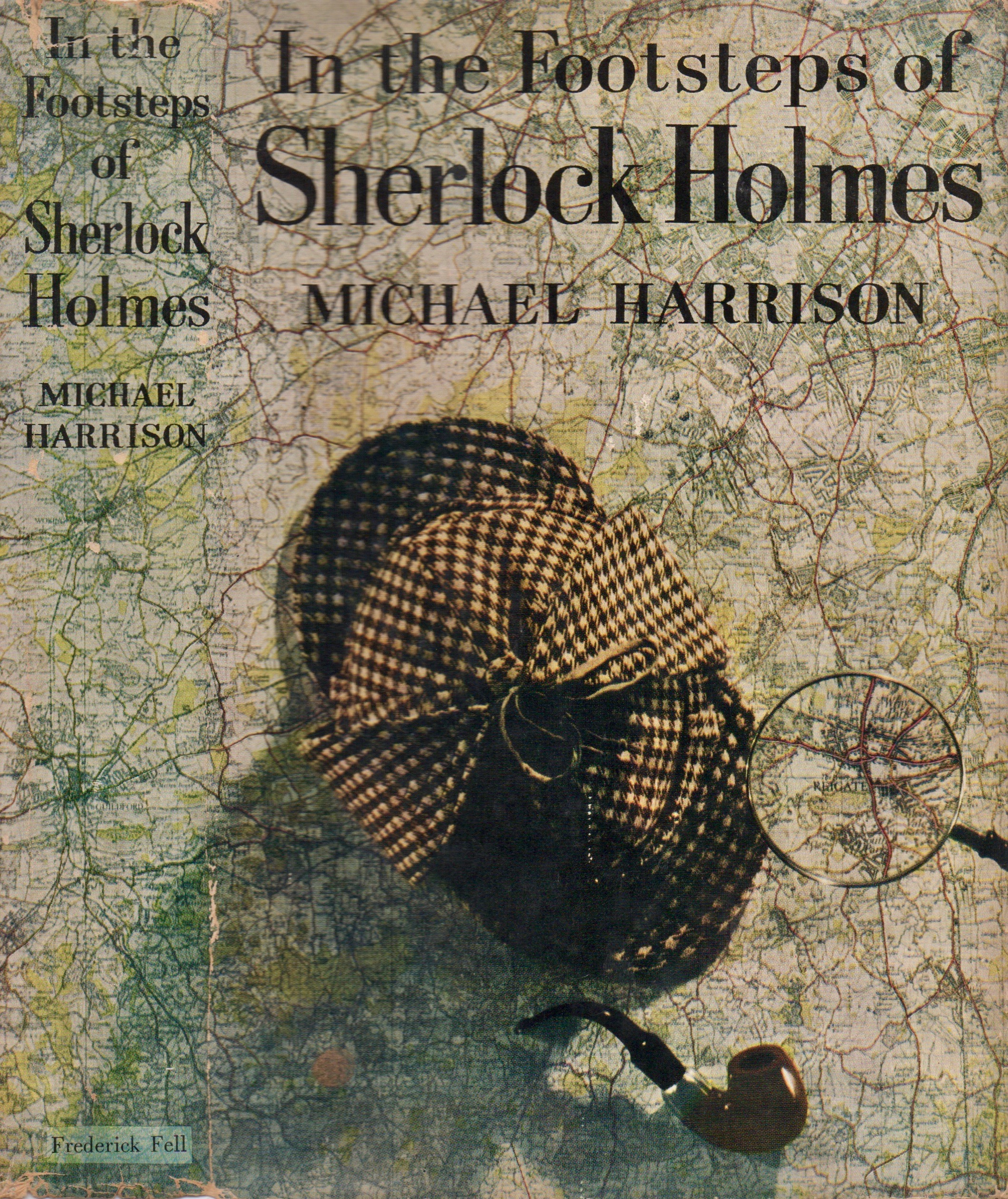

Private Life was often reviewed with Michael Harrison’s In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes, which appeared about the same time from Frederick Fell publishers of New York. This was Harrison’s first foray into the American Sherlockian market, and he would become a mainstay for the next two decades.

Anthony Boucher, long time crime reviewer at The New York Times, was a friend and admirer of Starrett and called him “one of the most attractive and infectious writers of books-about-books” in the country today. Boucher notes that while other books of Holmes commentary predated Starrett’s, “it’s hardy an exaggeration to say that the writings-about-Holmes truly date from the first edition of Starrett’s Private Life (1933).”

More:

“That small blue volume — scholarly without stuffiness, affectionate without sentimentality—has been long out of print. The welcome new version has been extensively expanded (and also, in a few places, regrettably abridged).”

By contrast, Boucher called Harrison’s book is “a rambling and unorganized book, and, in its divagatious way, a wonderful book.”

(I had to look up “divagatious.” It means “wandering.”)

Over at The New Republic, Rex Stout is a bit divided in his opinion. To find out who Sherlock Holmes is, Stout recommends reading the original 60 stories first, “but the next best is this book by Vincent Starrett. Though it quotes here and there a few brief passages from the stories, it is not a book about a writer or what he wrote, but a book about a man named Sherlock Holmes who lived and worked in 19-century London.”

Echoing a complaint about the original edition, Stout notes that “the book is not what the jacket calls it, a ‘biography of Holmes.’ ” In fact, Stout notes the longest chapter in the revised edition is given over to Mrs. Hudson. Still there is pleasure to be found here, says Stout, because:

“Mr. Starrett has so deftly and attractively assembled in a small space a multitude of data scattered throughout the sixty stories that even a student of the canon will feel himself refreshed.”

Let’s call that a qualified positive review.

‘The house in Baker Street still stands.’

One big difference between 1960 and the book’s initial appearance in 1933 is the fact that many reviewers were Sherlockians if not Irregulars. You’ve already heard from Collins, Buccholtz, Boucher and Stout, three of whom had an Irregular shilling to call their own. In 1933, there was no organized Holmes group to review books about the master detective of Baker Street. By 1960, Sherlockians were scattered around the nation and many had the opportunity to praise a book near and dear to their growth as Holmes devotees.

A. Mervyn Davies, while not an Irregular, clearly had the bug. Davies was the book review editor for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, and exhibited the same joy at a reprint of Private Life as any shilling-packing Irregular.

“Sherlockians all will give three cheers that the classic of their special branch of learning has again been made available. When it first appeared 27 years ago it was hailed as the ‘standard life’ of the sleuth, but it was soon out of print and became a rare collector’s item.”

Davies notes that readers would no doubt agree with a quote Starrett attributes to another Post-Dispatch reporter, Irving Dillard.

“The house in Baker Street still stands. It will continue to stand, as Irving Dillard has written, as long as the cold London fog rolls in with the winter and mischief is planned and thwarted and books are written and read.”

That sentiment seems as good a place as any to end this chapter.

Next Time: Back to Britain

Starrett’s revised Private Life was often reviewed with Michael Harrison’s book, In the Footsteps of Sherlock Holmes. Here’s the dust jacket from that book and a photo of Harrison.