Enter Riley Blackwood, Part 2: Magazine, Books and the French

The Bigger and Better Blackwood

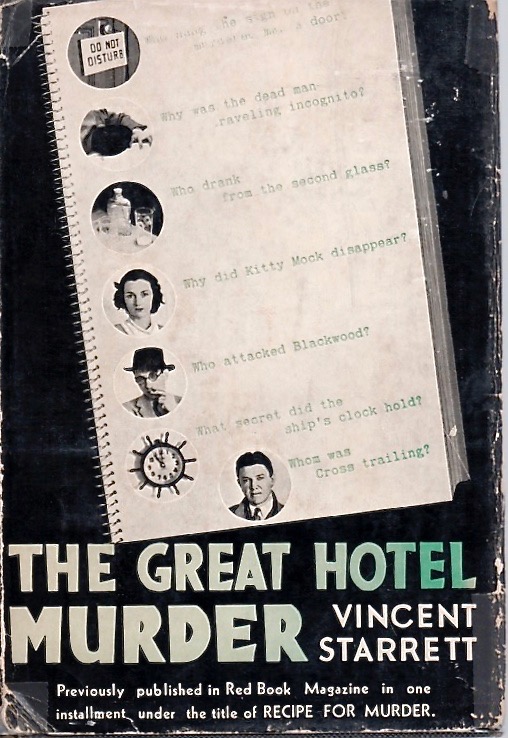

Last time, we reviewed Starrett's story as it was first published in the November 1934 issue of Redbook magazine. In this installment, we’ll look at how the story evolved from Recipe for Murder into its 1935 book publication as The Great Hotel Murder. As you can see, the book had a good publications history in the mid to late 30s.

Kitty Mocke became Kitty Mock when moving from Redbook, where this illustration appeared, to the novel.

What changed?

A lot! This is just a brief comparison.

The Title: Recipe for Murder became The Great Hotel Murder. I’m not sure how common the term was at the time, but Starrett uses the phrase “great hotel” numerous times during the story to describe the upper crust hotels in Chicago. The place where the murder took place is a “great hotel,” as is the pile across the street.

The Names: The “great hotel” in the Redbook original was the Hotel Mardena. It became the Hotel Grenada in the book.

While the major character names stay the same, there are numerous changes among the supporting cast and red herrings:

The gangster Gene Crotz or Gene Cross, depending.

Many folks had just one letter change: Hotel Manager Meffat became Moffat; Halderness/Holderness; Heviland/Haviland, and poor Kitty Mocke lost her ‘e’ and was just Kitty Mock in the novel.

Hotel Doctor Howard Merkham turned into Howard Marcus.

Detective Sgt. Croach evolved into Roach and Detective Brampton became Barry.

Gene Crotz became the more WASPy sounding Gene Cross.

Even dead men had name changes: Jeffery Collingham became Cottingham. And he was still dead.

One name was not changed, but should have been: Clelia Mason makes a brief appearance in both magazine and book under the name that surely should have been Celia.

The handsome Riley Blackwood from the Redbook edition.

Lots and lots of exposition, description and detail: The Redbook version was seriously cut so it could be squeezed into the magazine’s pages. The novel often has considerably greater detail that helps to round out the characters and the action.

Let’s look at one sample.

Redbook Recipe for Murder, page 130:

(Blaine Oliver is talking to amateur detective Riley Blackwood.) “Why do you do this sort of thing at all?” she asked at last. “In a sense, it isn’t any of your business.”

“It’s everybody’s business, isn’t it?” he retorted, but without conviction. “Murder is a fairly serious matter. However, that isn’t the answer. I’ve that kind of a mind, that’s all. A mystery fascinates me; I—“

Riley Blackwood as he looks on the dust jacket of the American editions.

Here’s Blackwood’s extended answer from the book, which tells you more about the amateur detective's character and motivations:

“It’s everybody’s business, isn’t it?" he retorted, but without conviction. “Murder is a fairly serious matter. However, that isn’t the answer. I’ve that kind of a mind, that’s all. A mystery fascinates me; I’m unhappy till I’ve solved it. The morality of it all concerns me less, I’m afraid, than the excitement of the problem. I used to be a reporter.”

Blackwood (who, as we proposed last time is a stand-in for Starrett) clearly believes that reporters are excitement addicts who lack any morality. You miss this in the Redbook version.

Book publication history: Who came first?

I have found three American editions/states of the book. There is also a British edition, but I’ve not been able to locate a copy. There are also two French paperback translations. We will do a survey of them all.

The order of the American editions seems to be as follows:

1. The Crime Club edition (an imprint of Doubleday, Doran & Co.) was published in 1935 and is a stated first. This edition was published by the Country Life Press in Garden City, NY.

I don't own this book in dust jacket, but I’ve seen a photo of the dj and it looks a lot like the one used for the Caxton House jackets. In fact, the Crime Club edition of the dust jacket, with its notebook of suspects on the cover, has red ink for the notebook lettering and the title letters. That’s the same combination we’ll see in the Caxton House issues. The back of the dust jacket advertises other Crime Club mysteries.

Inside, the “Other Books by Vincent Starrett” acknowledgment is extensive, with nine volumes listed there, including The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, all three of his Walter Ghost detective novels, the fantasia Seaports in the Moon, the anthologies The Blue Door and Coffins for Two, plus two books about books: Buried Caesars and Penny Wise and Book Foolish. It’s a generous listing, especially considering three books (Seaports, Caesars and Penny Wise) were published outside the Doubleday family.

2. The Sun Dial Press edition came out in 1937. Like the Crime Club edition, it was also printed at the Country Life Press in Garden City, NY.

The dust jacket cover is the same as the one for the Crime Club, but has blue instead of red ink. Also, the list of books on the back of the jacket are Sun Dial Mysteries, not surprisingly.

“Successful Men Read” is the title for this list of books and you have to wonder how many successful men read Murder in the Madhouse or President Fu Manchu (well, I read the second one years later in a cheap paperback edition and I’m mildly successful, so never mind.)

Inside, there is no list of “Other Books By Vincent Starrett.” But the type certainly looks the same as the Crime Club edition. I’m no expert, but it looks like the same plates were used for both books.

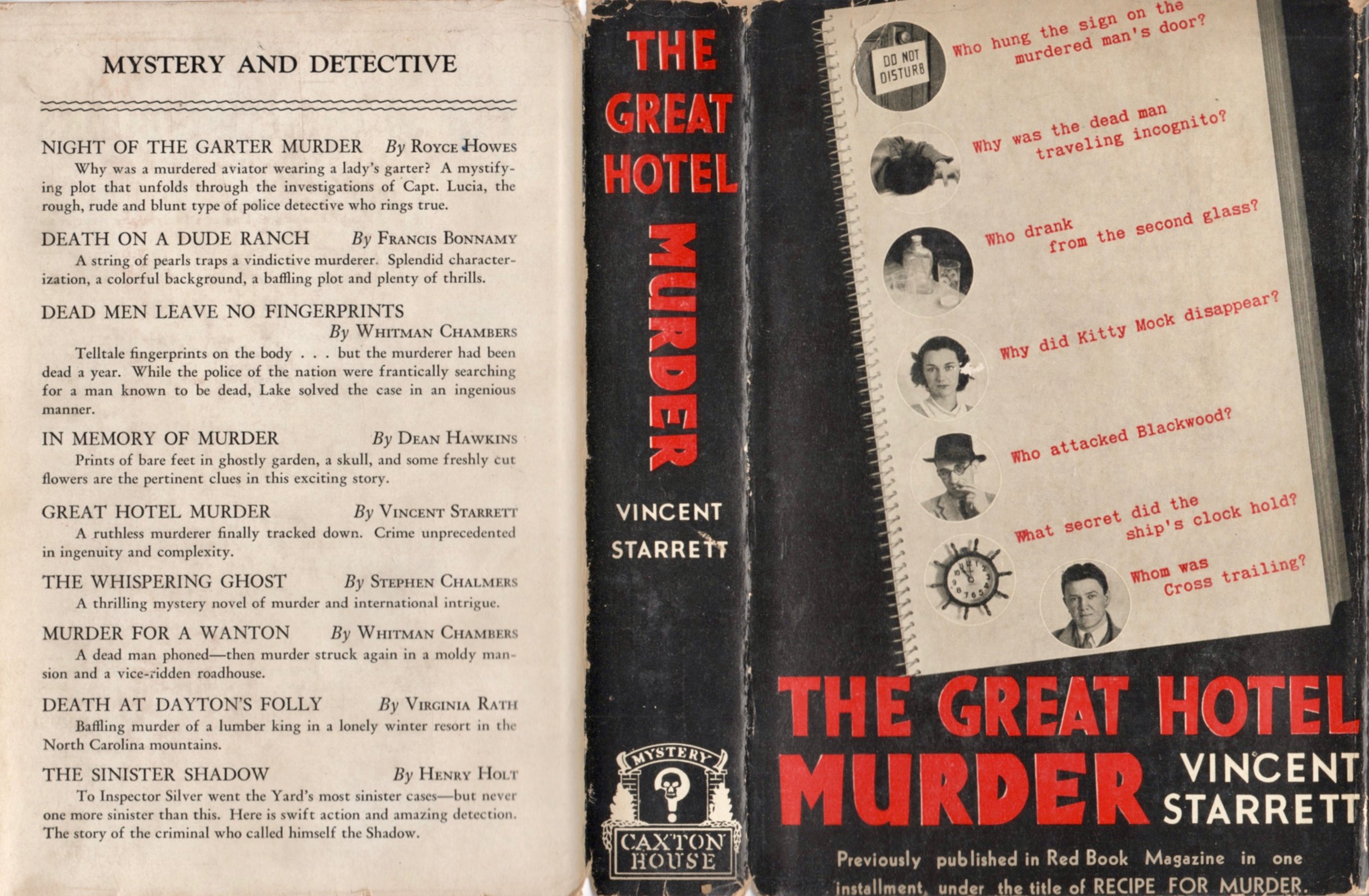

3. Two Caxton House editions, with either blue or green covers, were last, published in 1939.

The dust jackets have red ink, and the dj copy is the same. The back of the dj has a list of Caxton House mystery and detective novels, and inside back dj flap points you to the inside of the dj cover, where a list of Caxton House novels await your decision to order by mail.

Inside, there is a much more modest “Other Books By Vincent Starrett” list: The Great Hotel Murder (which is the book you’re holding and not an “other” book) and Murder on “B” Deck, which was published in 1929.

I’ve not done a word-for-word check, but the story itself appears to be identical to its earlier brothers.

How were the reviews?

Before we shift to France, a brief word on the book's reception by the critics: They hardly noticed.

The book and the movie came out in 1935 and most of the attention in the media was given to the film version, which we will take up next time. I did find a few book reviews. Let's start with a few comments from the anonymous Chicago Tribune reviewer from May 25, 1935:

"Everybody in the book, pretty and good, plain and bad, falls under suspicion before the rather melodramatic conclusion is reached. Personally, I was satisfactorily fooled, but maybe you'll be too smart for the author and his machinations. Whether you are or not, you'll find the book very entertaining reading and all its more puzzling coincidences fall deftly into place."

The New York Times also gave the book a few graphs, with this heartening conclusion:

"Mr. Starrett has devised an ingenious plot with enough complications to keep the reader guessing, and he has placed the solving of the problem in the hands of a man who, without being a miracle worker, is capable of clear thinking and taking advantage of the breaks when they come his way. The Great Hotel Murder makes good reading."

The British edition gained some attention, even in the Times Literary Supplement, where the anonymous reviewer said:

"An amateur detective (why is it a tradition that these must always be rude?) does a great deal of intricate reasoning before alighting, rather by chance, on the true culprit. In short, the story is exciting enough to read, though weak in the joints when examined too closely."

Le Crime De L’Hotel Granada

As I mentioned, I also have two French paperback editions, with evocative covers. I’ve briefly treated the topic before and I'm stealing from myself here, with some additions:

The French editions show the influence of that nation’s interest in roman noir novels from the hardboiled school of writers. Reflecting this trend, both French editions have lovely lurid covers.

1. Le Crime De L’Hotel Granada was translated into French by Simone Lechevrel and published in 1937 as No. 113 in a series of mysteries by the Nouvelle Revue Critique at 11 Rue Francois-Mouthon, Paris.

(Lechevrel was a popular translator of the period, taking on books by such well-known English language writers as Ellery Queen and Eric Ambler.)

The series included translations of stories by such popular international writers as Earl derr Biggers (creator of Charlie Chan), Ellery Queen, R. Austin Freeman, Nicholas Blake and John Dickson Carr (writing under Carter Dickson).

The large metallic syringe on the cover suggests a lurid tale of drugs and death, rather than the cerebral puzzle in the American editions. (Embarrassing admission: I can’t read French, so can’t comment on the quality of this or other translations. Je m'excuse.) There is a morphine user in the story, but the syringe in the story is clear, since Riley Blackwood describes the color of the liquid inside.

2. Ten years later, the novel was republished by La Maitrise Du Livre at 7 Boulevard Morland, Paris. Again, it was part of a series of mystery paperbacks, but with the exception of Dorothy Sayers, the authors in the second series are less well known in this country today.

Once again, the cover offers a noir scene, with a shadowy hand reaching towards a tray of drinks that suggests poison is on its way. It's a pretty good suggestion of what happens in the novel, if you ignore the fact that the bottle's label is printed in French, a detail Starrett didn't mention.

The back cover remarks that the detective story is the "perfect distraction" offering an exciting mystery to be read and enjoyed.

So that's it for book publications that came during Starrett's lifetime. Of all of Starrett's fiction novels, The Great Hotel Murder had the longest shelf life and and the greatest number of versions. The story might be, as the Times Literary Supplement noted, weak in the joints, but Riley Blackwood had enough energy to drive the plot along in its various incarnations.

The question is: Can Riley Blackwood carry a motion picture? The answer comes in our last installment.

Grab your popcorn. We'll reserve two seats in the balcony.