Books and Bipeds: The 2015 BSI Dinner weekend

A few new books, but an even better story of friendship.

Scott Bond's handsome cover artwork graces this year's dinner program.

I go through book buying cycles while in New York City for the annual birthday festivities, and by “book buying” I’m talking about purchasing books that are related to Vincent Starrett. It seems like there won’t be anything interesting for a few years and all of a sudden a wave of things will become available.

Some items are out of my financial range: I would love to own a copy of The Unique Hamlet, but spending several thousand dollars of my mortgage money on the little pamphlet simply isn’t going to happen.

(To some, that kind of decision means I’m not a “real” collector. So be it. I have a roof.)

All of this is to say that the last Baker Street Irregulars dinner weekend was a success from several points of view, not the least of which was filling in some gaps in my collection. There was also an unexpected act of friendship that resulted in the best purchase of the weekend.

Let’s start with a few choice books.

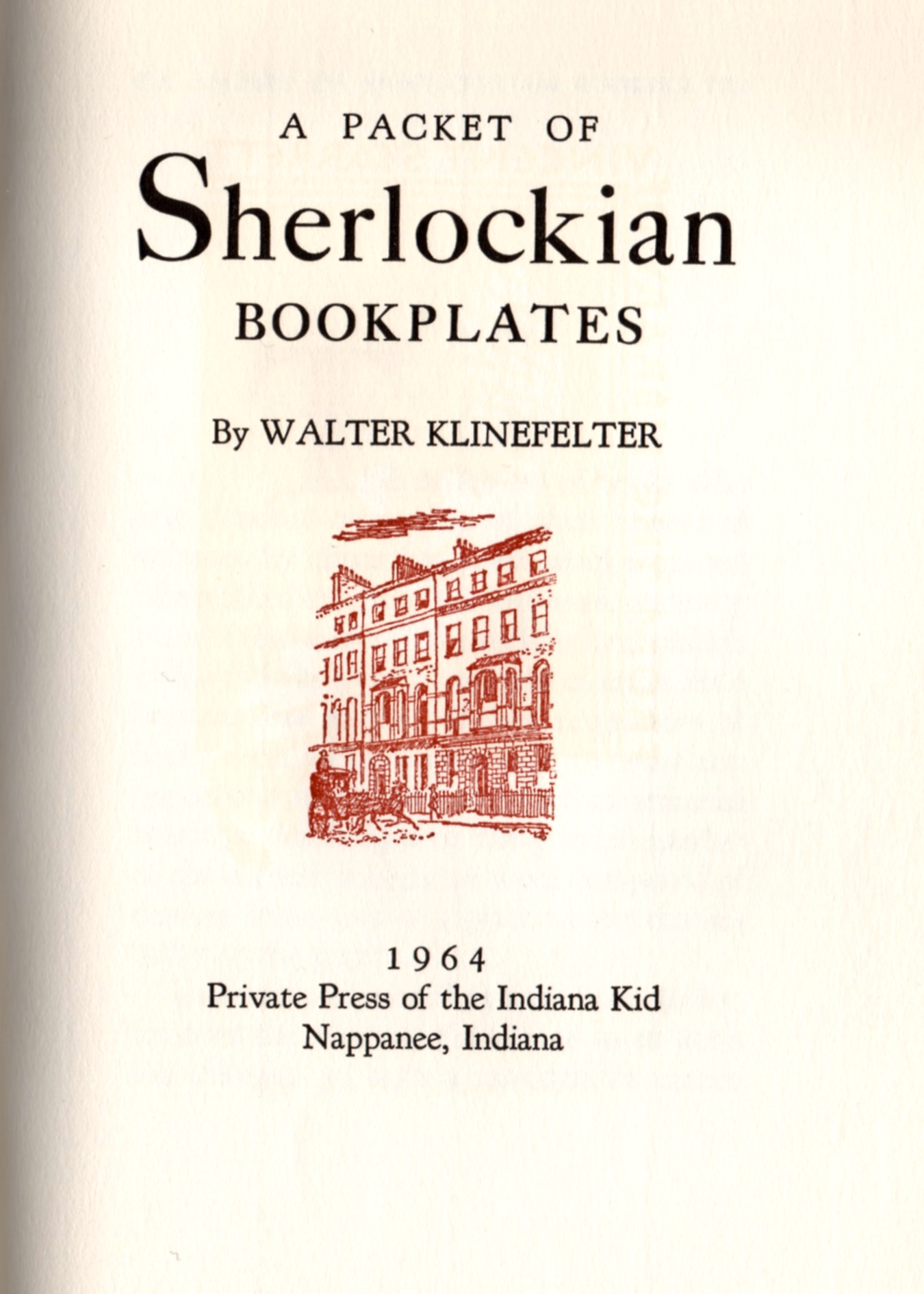

A Packet of Sherlockian Bookplates

Walter Klinefelter’s 1964 booklet has a title that makes it seem like it’s not a booklet at all. A Packet of Sherlockian Bookplates sounds like it should be an envelope with several bookplates in it. In fact, it’s a slim volume with 13 unnumbered pages, but several fine illustrations.

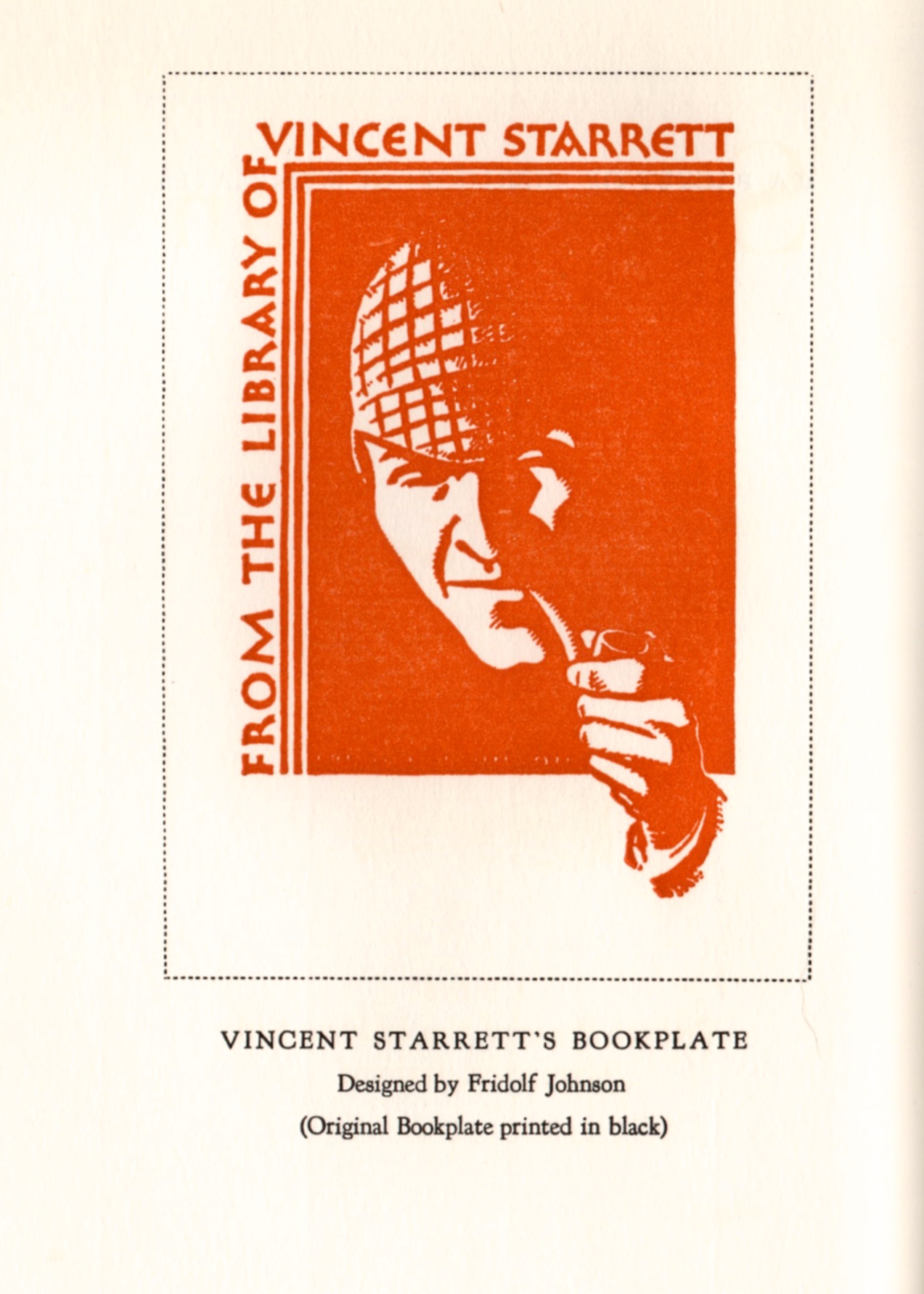

As you can see, the book’s cover and frontispiece both bear Vincent Starrett’s famous Sherlockian bookplate. Regular readers (both of you) will remember that bookplate was drawn by Fridolf Johnson and was also the subject of not one, but two articles here in 2014.

Klinefelter, who lived about an hour west of where I live now in Pennsylvania, was a close corresponding friend of both Starrett and Morley. Besides Starrett’s bookplate, perhaps the best known in the book is that of Edgar W. Smith.

Klinefelter devotes his book to “a number of collectors who have become so devoted to the memory of Sherlock Holmes that they must have every volume, every pamphlet, every article that has ever been written about him, and having assembled a sizeable collection, feel impelled to attest their connection with it by making use of an ex libris that has something to do with the greatest consulting detective of all time.”

He goes on: “To establish priority among this select company should not be difficult. By every token it belongs to that dedicated Holmesian scholar Vincent Starrett, who has gotten together a notable collection of Sherlockiana long before Beeton’s Annual of 1887 had become a much desiderated item, even before the Baker Street Irregulars were reactivated.”

Edgar W. Smith's bookplate.

Klinefelter describes Johnson’s bookplate showing a Holmes with “a hawklike cast of countenance, piercing eyes, a curving pipe, and a close-fitting deerstalker, all of which contribute to the making of a bookplate distinguished enough to grace the very finest volumes of Sherlockiana.”

There were only 150 copies of A Packet of Sherlockian Bookplates, which was printed on the hand press of James Lamar Weygand at the Private Press of the Indiana Kid. Weygand was an expert on printers marks and private presses and he produced more than 30 books over the years. More about Weygand can be found at BriarPress.org.

I have wanted a copy of this book for a while and was pleased to pick one up. But as fellow BSI Dana Richards noted, “I thought you would have had one of those by now.”

Oh well. We can but try.

A Conversation with Vincent Starrett

Klinefelter also is responsible for this little booklet, published by The Anthoensen Press of Portland, Maine in a limited edition of 50 for Christmas, 1947.

The piece, with only five pages of text, was originally published in a Chicago-based literary magazine known as The Step Ladder, edited in part by the husband and wife team of George Seymour and Flora Warren Seymour. (See the first note below.)

Seymour’s Q&A with Starrett revolves around an apparently dull book catalogue.

Starrett: “An uninteresting book catalogue! Nonsense! Impossible, because (that is) a contradiction in terms. Let me see it.”

Starrett then flits through the catalogue inventing preposterous back stories to the leaden-sounding books for sale, making them all seem like the kind of treats you could not pass on. The more incredible the story, the more intrigued Seymour becomes by it all.

It’s a tour de force in a few hundred words, and shows why Starrett found it difficult to pass up even the blandest old tome. His romantic nature allowed him to create all sorts of reasons why a particular book should be part of his collection.

I didn't need a romantic back story to want this pamphlet. The fact that it was about Starrett and book collecting was enough for me.

That lapel pin

The best item from the weekend was not a book printed by Klinefelter but a pin, and how it came to be on my lapel.

As has become the tradition on Saturday mornings, I was up at 7 and out by 8 to have breakfast with Peter Blau and the Mrs. Turner's Thames Club Breakfasters (ask me later), before wandering over to the huckster’s room in the Roosevelt Hotel.

After roaming the huckster's room a bit I ran into Steve Rothman, who asked if I had been to the table that Dick and Francine Kitts were staffing. I had walked by, but there was a crowd and I didn’t notice anything of particular interest. “Go back and ask her about the pin that I said I wanted to buy for you,” said he.

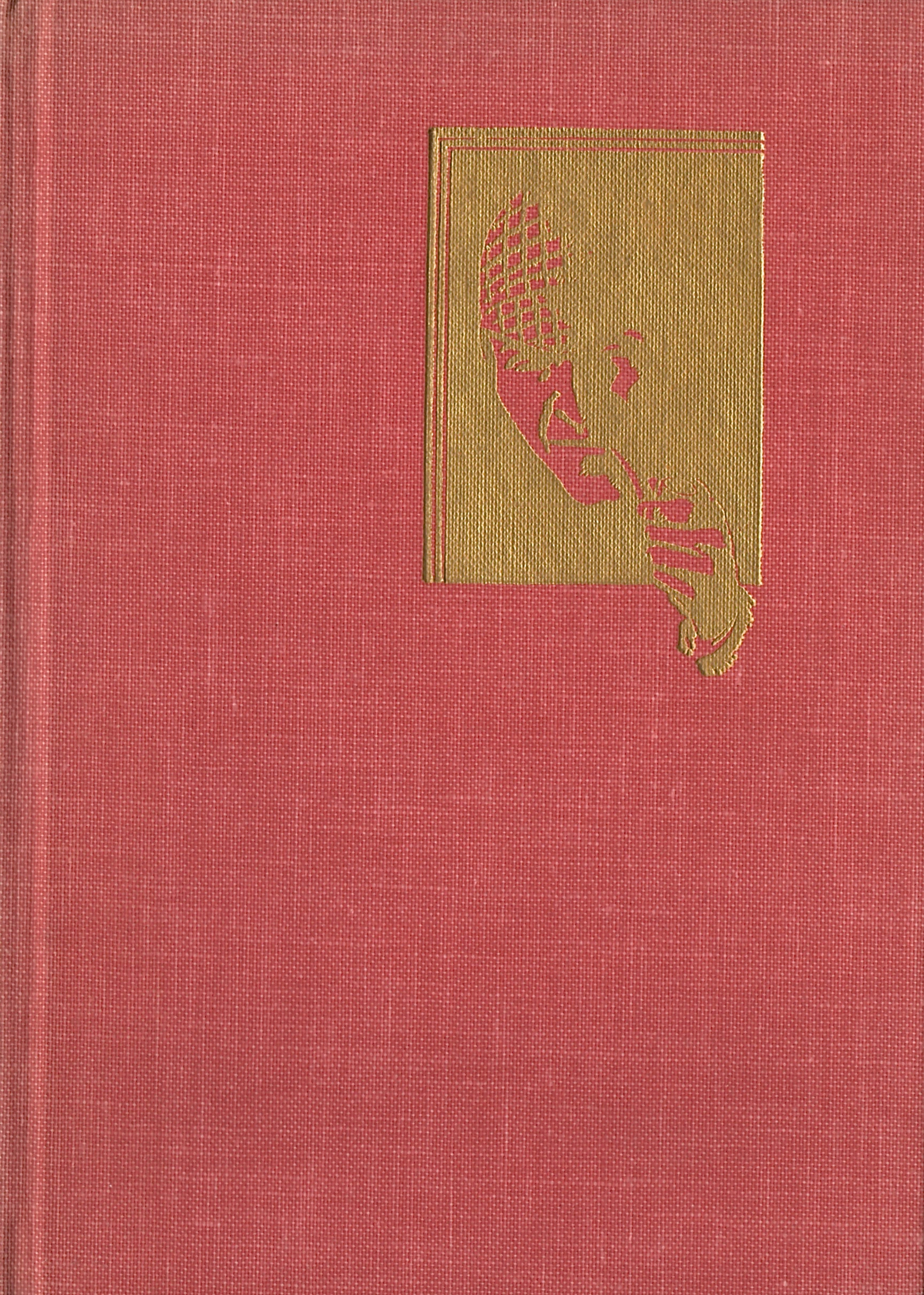

Turns out the pin is the one you see here, created from the famous Vincent Starrett portrait by Don Loving, which can be found on the back dustjacket flap of the 1933 first edition of The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Francine was smiling brightly when she brought it out, affixed to a slip of paper that read "221."

Don Loving's photo of Starrett.

Turns out Steve had walked around the area earlier, seen the pin, thought I would like it and asked her to set it aside until he could find out if I already had one.

I had missed out on these pins when they were first made, so to get one now was really wonderful.

I was thrilled to have it, and equally delighted that Steve had been kind enough to think of me. Thanks to him and Francine. I will wear it with pride. What a thoughtful friend!

The More You Know

- Flora Warren Seymour’s name rang a very distant bell when I saw it, and in hunting around, I discovered that she was the first woman member of the Board of Indian Commissioners in the early years of the last century. She also authored a series of children’s books about Indians and what we used to call the Wild West. The Boy’s Life of Kit Carson, by Flora Warren Seymour and published in 1942, was one of my favorite books growing up. It was a highly romanticized version of Carson’s life, but for a lad who watched “Davey Crockett” and “Daniel Boone” on television, it fit perfectly.

- There were a few other Starrett-related items from the weekend, especially the new biography of Bliss Austin. One of Austin’s best articles was an early attempt at tracing the history of Starrett's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. But these will have to wait until another day.